The gentle pleasures of a summer's woodland walk have become darker and duller, thanks to fertiliser from farms and the ancient art of coppicing dying out.

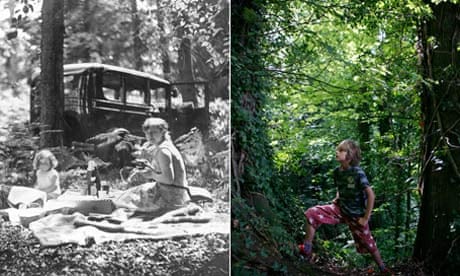

The discovery came after botanist Sally Keith retraced the steps of the pioneering ecologist Professor Ronald Good, who cycled the lanes of Dorset in the 1930s, recording in great detail the plants he found. Of the 1,500 woodland sites Good noted, Keith revisited almost 100, as close to the day and month of the original survey as possible.

She found that the unique character of each wood had vanished, and that the canopy of leaves was more dense. "Holly was in nearly every wood now; in the past it was only in half," said Keith, a postgraduate researcher at Bournemouth University. Hawthorn, ivy and foxglove were also far more common, while distinctive highlights found by Good such as yellow iris, devil's-bit scabious and red bartsia had disappeared.

"In the past, the woods would all have been quite different, but now they share many of the same species," said Keith.

"It's both fascinating and disturbing," said Professor James Bullock at the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology in Wallingford, Oxfordshire, who worked with Keith. "It's likely to be going on undetected elsewhere, but as we have Good's maps we can see it here. We are losing diversity on a large scale, with certain species driven out across the whole landscape. We can expect it to be happening across the country and Europe, as the same things are happening there."

Paul Hetherington, of the Woodland Trust, agreed: "Lots of holly has crept in [across the UK]. It's very dark and dense. We take holly out, as it kills off all the undergrowth."

Keith believes there are two key reasons for woodlands becoming less distinctive. First is the end of coppicing, in which wood was harvested from different parts of a forest in rotation, creating bright clearings and letting in light to favour less common plants, such as red bartsia. In her study, 117 species had vanished, while only 47 new plants had arrived. "Traditionally, woodlands had glades, meadows and ponds, giving many more habitats and so many different things to see, rather than wall-to-wall trees," said Hetherington.

The other key reason is the increased run-off of nitrogen from farms, due to increased fertiliser use and intensive livestock rearing. Some plants, such as holly, thrive on high nitrogen levels; others do not. "Many woodlands are now just fragments surrounded by farmland," said Keith, adding that this exacerbates the problem.

Nick Herbert, shadow environment secretary and Conservative MP for the constituency of Arundel and South Downs, said: "It [Keith's work] shows that we cannot take the natural environment for granted and that we have to work hard to conserve it through traditional management."

Last week Herbert launched a consultation called Future Countryside to consider radical solutions to environmental problems, including making water companies pay farmers to use less fertiliser, reducing the water purification costs paid by the public.

"We have a moral duty as the dominant species not to damage the environment around us," said Bullock. "But we are also losing some aspects of the history of our country as well. Local woods are little museums of human and natural history."

Woodlands also provide "eco-system services", such as purifying water, preventing flooding and storing carbon, he said: "And the more species you have, the better you provide these services."