On this Thanksgiving, among the things I'm grateful for are Rush Limbaugh and the Tea Party mad-hatters for injecting a little humour into turkey day. In their madrassa-like study courses and his broadcasts, they accuse the sainted Plymouth Rock Pilgrims of the crime of "socialism" or "collectivist communism" because the Massachusetts settlers pooled their scarce resources to survive that first starving winter in America. Aha!

But soon the Pilgims came to their senses, when they saw that "socialism does not work", and, like good little capitalists, divided their property privately and prospered. So, to hell with all that liberal propaganda about sharing food with Squanto and his Patuxet Native Americans, who saved the Pilgrims by teaching them how to subsist in the New World. The free market lives!

For the rest of us, there's so much else to be grateful for: Lady Gaga, my union's health plan, Michael Moore's indestructible ego, and all the geek-elves who helped invent my gorgeous little Mac mini. The money that went to economic "wizards" like Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs and Citigroup's Sandy Weill and all those bonus babies from Bank of America (my bank), Merrill Lynch and others should go instead, in gratitude, to Larry Page and Sergey Brin, who invented Google, which has saved me incredible amounts of shoe leather. How does Google always know what I'm thinking? Thank you, God, for algorithms.

I'm grateful that the 7 million customers who queued up for the latest cold war killer video game Call of Duty: Black Ops, currently glued (like my teenage son) to secret agent Alex Mason assassinating zombies and Fidel Castro, haven't gone out to replicate the violence in the real world. Yet.

Thanks also to myself for being so low-tech that I can barely handle the internet and haven't yet figured out how to make Mark Zuckerberg richer by navigating his increasingly obscure Facebook. I sneer at Twitter but also know that it helped save lives in hyper-violent Mexican cities like Monterrey and Reynosa, where citizens use the online social networking service to warn fellow residents of potentially dangerous shootouts. If I had the will, energy and time to fulfill my karmic destiny as a social activist, I'd be on Twitter all the time.

I'm grateful that my cellphone is a 15-year-old Nokia dinosaur that cannot text or take pictures because it is liberating to sit in a lonely diner sipping a cup of coffee and, undistracted, do the unthinkable in the electronic age and privately think my own dark thoughts, as in an Edward Hopper painting, without having to be distracted or, in Zuckerberg's immortal mantra, "socially connected".

On a dark cold night, when my extended family and I are warmly gathered for a traditional Thanksgiving blessing, I'm so grateful for those who cannot be with us tonight. They're the lonely, isolated souls, often from small resister groups like Catholic Worker and Plowshares, who actually do the protests and political organising that I should be doing, by passing out leaflets to unfriendly motorists or posting on a school board issue or "witnessing for peace" on busy San Fernando Valley street corners or making the exhausting bus trip to Fort Benning's Terrorist School for Training Cops in Torture (oops, Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation) and getting arrested by roughly unloving local police.

I've a bad back, so my hat's off, in thanksgiving, to dissenters who climb fences, sneak into military bases and sit down in the path of an F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. Or, in the words of the passionate free-speech activist Mario Savio:

"There's a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious… that you can't take part… And you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you've got to make it stop."

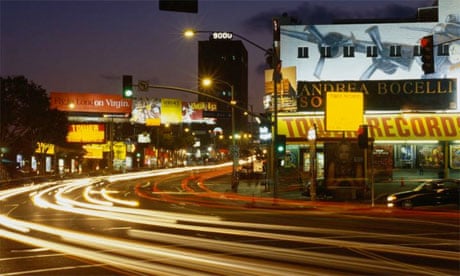

I like my life for the first time in decades. Los Angeles is an amazing place. It takes time and patience to retrain a London-informed eye like mine to appreciate the subtleties of season and landscape, beach and mountain. But then, I realise that, in many ways, LA and London are similar, sprawling, anonymous and wide open to creativity, if you ignore the conventional wisdom of the ever-present "no". The movie business may be "a war where nobody dies" (well, almost nobody), but in its own peculiar way, it's remarkably stable and traditional and always good for a surprise – good and bad. I love driving down Sunset Boulevard and stopping at a red light to look over and see Clint Eastwood in the next lane. ("Hiya Clint, loved Gran Torino!" "Uh… Thanks.") Or run into Bruce Springsteen at Whole Foods reaching for the same peaches I want.

Sometimes, at a studio, tensing up while rehearsing to pitch a screen story, just before I go into the conference room, I'll stop and stare at myself in a mirror and think, "Wow, I'm in Hollywood!"

At holiday time, when US and UK soldiers, sailors and marines are far from home to fight in a vicious losing war, I feel mixed emotions of sorrow and gratitude for them. "People sleep peaceably in their beds at night only because rough men stand ready to do violence on their behalf," George Orwell is misquoted, and misinterpreted, by professional war lovers. All right, we get the idea.

Maybe I'm influenced by the example of my father-in-law, a Navy veteran of the Pacific war, sailor and pilot, anything but a rough man, who bravely did violence, and had violence (by torpedo and kamikaze) done to him, on my behalf. I'm devoutly grateful he was spared to father his daughter, my wife, so that we could make our teenage son who, with luck and protest, will never have to go into the Korengal valley or its like in Yemen or Iran.

Finally, almost every night I dream about London, where I learned to be a writer and deposited most of my craziness. Over time, I became a normal Londoner and travelled almost every day on the old Routemaster doubledecker bus and on the Tube. Irrationally or not, I think of the dead and wounded of the 7/7 bomb attacks, on the Circle and Piccadilly lines and the Number 30 bus (which I rode regularly), who took a bullet meant for me.