The document dump has begun. On Sunday afternoon we entered what is sure to be another week, or more, of WikiLeak wonderment. Hundreds of thousands of classified U.S. State Department cables will be dribbled out day after day in a handful of newspapers with titillating revelations about foreign affairs that make us all, in the felicitous phrase of The New York Times, "global voyeurs" looking at the inner workings of diplomacy.

Already, despite the Obama administration's best efforts at preemptive damage control, it's obvious that many of the revelations could make very dangerous situations even more precarious, especially in the Middle East. The problem is what the good ol' boys I grew up with used to call "fightin' words." There are certain things you just don't say to your enemy's face, or anywhere in public, unless you want a showdown.

Now, suddenly, we have several Arab Gulf leaders revealed all too vividly and publicly wishing for the United States to rid them of the Iranian regime headed by President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. That whispered sentiment hasn't been a secret, really, but this frontal revelation is an insult likely to provoke an already dangerous Iranian regime into further rash adventures.

Nor has it been a secret that Yemen's President Ali Abdullah Saleh has allowed Americans to attack Al Qaeda installations from the air, as long as he could deny the country was doing so. But now we have him quoted in an official State Department cable telling U.S. Gen. David Petraeus last January, "We'll continue saying the bombs are ours, not yours," followed by Yemen's deputy prime minister laughing about lying to the Yemeni Parliament. That bit of dialogue is not just embarrassing, it's going to make the covert war against the most dangerous Al Qaeda franchise that much harder to wage.

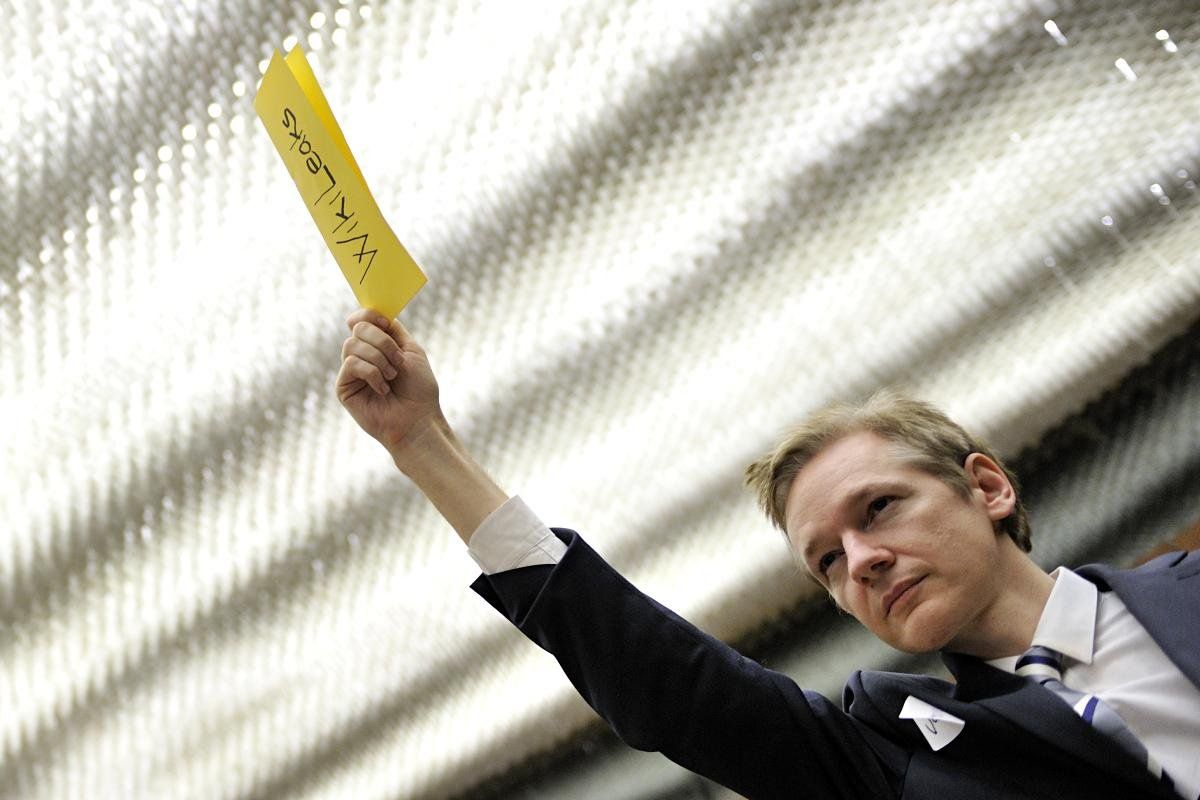

The first and most lasting casualty of this massive avalanche of documents classified "confidential," "secret" and "noforn" (not for foreign governments to see) is going to be precisely the "transparency" that WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange says he advocates. "Transparent government tends to produce just government," he opined in July after an earlier dump of military dispatches about Afghanistan. But the fact is, transparent diplomacy is nothing but press releases.

The problem the State Department faces now is not just the difficulty of having frank conversations with allies or secret negotiations with enemies who think—who know—it leaks like a sieve. It will also be harder to have frank exchanges within the United States government itself. To avoid this kind of massive leak in the future, documents will get higher classification and less distribution, and a lot of the most important stuff may not be committed to the keyboard at all.

As a former U.S. ambassador in some of the Middle East's most sensitive posts wrote me (privately) this morning: "The consequence will be even less written reporting and communication—a disaster if you ever want to reconstruct what happened. It is already bad and now will be even worse. Everyone (or those in the know) will be passing info verbally. Ever play that whisper game as a kid?" He means the one where you pass a message from mouth to ear and discover it's utterly distorted at the end of the chain. "Yep!" he wrote, that's what internal communications are going to be like.

Apart from our voyeuristic interest (and I admit I'm fascinated by the inside picture of delicate talks with China and titillated by tales of Muammar Kaddafi's buxom "Ukrainian nurse") I have to wonder what the point of this particular document dump is really supposed to be.

This isn't like the Pentagon Papers, or even the Afghanistan and Iraq documents that WikiLeaks poured out earlier this year, which helped to expose or, in most cases, confirm what we already knew about very badly conceived and executed wars. This would appear to be a direct assault on the whole idea of confidential diplomatic correspondence. And that's not just a bad idea, it's a stupid one. "I think Assange is an anarchist—he's not really interested in getting at important policy issues—just expose it all," says Ryan Crocker, the American ambassador who helped pull Iraq back from the brink.

I'd think anybody who writes e-mails or goes on Facebook would understand the issues here. You pick and choose the people to whom you want to send information, including a certain amount that you're happy to have in public. But you feel violated if your e-mails are passed on without your consent, and on FB, as we know, there are increasing demands for greater control over content, so that not everybody gets to see everything you post.

That's precisely what the relatively low level of classification put on these documents is supposed to provide for diplomats: a modicum of discretion. Transparency, as something we should encourage in government, is a good principle and good practice. But there is a moment when too much transparency, instead of facilitating communication, helps to stifle it. And I think that moment is just about upon us.

Dickey, NEWSWEEK's Mideast Editor and Paris bureau chief, is the author most recently of Securing the City: Inside America's Best Counterterror Force—The NYPD.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.