We asked our readers to submit stories of their service or the service of their loved ones and friends. Here are some of the poems, writings, and artworks we received.

Submitted by Amber Stone, of Savannah, Ga. She wrote this poem upon returning from duty in Iraq.

Fear

The smell hangs on your

soggy cargo pocket—

almost like the rain

drenching your boots.

You try to shake it as

if it's a fly on your shoulder

but it only makes you

feel colder.

You press your hand

against the clay door

and it vibrates as if

to say don't enter—

they're here.

And the moment comes

when you slam into it—

knees weak with it,

a tiny drop falls

Giving you just enough

to raise your weapon

and take perfect aim

for there is no more.

Submitted by Kathy Partak, wife of Sgt. First Class David Partak, California Army National Guard

Here is a video my husband made for our son, Mason, and me while he was deployed during Christmas 2004. My husband has had two dreams in his life: to fight in a foreign war and to be a park ranger in Gettysburg. He is finishing his degree in military history (both times he was pulled off course were for deployments—once for the Rodney King riots and the other for airport duty after 9/11).

We are selling our house and becoming renters so that when an opportunity arises for him to take his dream job, we can move from California to the East Coast. It's not easy coming back after a deployment, for anyone—soldier or family. Luckily for us, we are very stable in our marriage and family and not only did we get through it, but we are united in following our dreams!

Poem submitted by Rich Blake, of Baltimore. He wrote this while serving in Iraq.

A Burning Map ...

So much yearning, but no such thing as turning back

A path of light forgotten, my life is now a burning map

Concerning myself only with the journey back

Rays of hope that shimmer, get dimmer, and return to black

One of few who stood in line, strong but too shook to look behind

A crook at times, a wrong turn, if only we had took our time

In nooks we find piece of mind; in time we shared and cared for blind

Covered in sand in the land of the sun, blood on our hands and scared to shine

A turning page, a raging flame with the scent of sage

Put out by fountains short of mountains' peaks beneath our perfect stage

Descending, falling, but stalling to remember all the laughter

Chapters wrote of endless hope, knots on friendship's rope, and nothing captured

Said and done, the hourglass sands bled upon

Pressured but never measured up, still treasured when we're dead and gone

A burning map; ties to distant lives are severed

Clever, those who remember details upon the trails they weathered

Submitted by Debe Loughlin, of Portland, Maine, who served with the U.S. Coast Guard in the late '70s.

Being a woman, a daughter, a mother, a sculptor, and a military veteran is an unusual mix. I am from three living generations of veterans. My father was a hard-hat diver in WWII; he chased the Desert Fox across Africa. Myself, I never saw war but dealt with it on a different level. I saw the effects of war on others through my billets in the U.S. Coast Guard, and my son was in the Air Force, stationed in Kirkuk, Iraq, in the beginning of the Iraq War. We have all survived and have never regretted our commitment to our country.

As an artist, I started making work that expressed an obvious connection to war a long time ago. I realized I felt like I had always needed my father's approval—making him proud, I joined the military at a time when Vietnam was just ending. Years later, when I became an artist, I created a piece of sculpture that was small and delicate, created by altering our ribbons and plugging them into slots in an old print-type box. His has his military language and mine has mine, and they "communicate" when hung together. I made the piece, hung it, and called it Approval. One vet to another. It didn't seem to be about father-daughter but more about vet to vet—the language was visual.

Then my son went into the military a few months before 9/11 and our lives changed. My work continued, and subconsciously I started making sculpture that expressed my daily thoughts about where my son was going and where he was when he got there. My work started to become heavy, burdensome, and dark. It also started to become my voice. My thoughts were of the dichotomy of war. No protection but lots of life safety lessons, knee-jerk reactions by our government to send our soldiers to protect us and our Constitution, U.S. equals us. I fought that war mentally alongside my son and my father, the three of us. And I kept making lots of work to express my thoughts—the language turned into sculpture.

The Post Modernist Life Jacket is the dichotomy of a life jacket that saves no one. We are all drowning in war and it costs us physically and emotionally. The making of objects for me is my way of visually explaining my language, and sometimes that is the language of war.

Submitted by Karen Kennedy, wife of Sgt. Joseph Thomas Kennedy, who died on July 7, 2010.

This Veterans Day holds a particularly new meaning. Twenty years of serving his country was the plan Sergeant Kennedy had from the day he entered the U.S. Army. As any human has realized, things don't always go according to plan; in fact, you are mostly left wearing a look of disappointed bewilderment. An excited young soldier says to his first sergeant, "Sir, I'm getting married and taking leave in July." Searching for the words, first sergeant angrily states, "Soldier, if Uncle Sam meant for you to have a wife, I'd-a issued you one!" We got married anyway. Our first daughter was created in love. A field maneuver suitably dubbed "Victory Focus" brought us our little sunshine, Victoria.

Civilians have the luxury of ignorant bliss. The last 15 years as a military wife have given me the panoramic view of a life I wouldn't recommend to anyone I liked. Long deployments, PTSD, and wives who wear their husband's rank on their arms are just a few of the things I've encountered.

Three children (one diagnosed with lupus at age 17), one gone man, school, work, and every other imaginable activity was my life. There are perks to military life. Medical care, although not always topnotch, is the best plan this country has to offer. Shopping at the commissary and PX (post exchange) or BX (base exchange) gives soldiers' families the opportunity to save money on the final bill by not paying sales taxes. Programs to take care of soldiers and their families have greatly improved over the years.

This Veterans Day will have new meaning for my family. It is the first I will spend as a widow. Sgt. Joseph T. Kennedy and his daughter Brittany Danielle Carson went to the giant base camp up above. He lost his battle with PTSD, and she fought lupus until she couldn't fight any longer. We love and miss you, Sergeant Kennedy (K-Rock) and Brittany (The Boss). Rest in eternal peace.

Dedicated to the memory of Sgt. Joseph Thomas Kennedy (April 18, 1972, to July 7, 2010) and his daughter Brittany Danielle Carson (March 21, 1985, to Aug. 31, 2010).

Submitted by Matthew Thompson of Philadelphia.

I enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1999 and served nearly five years on board the USS George Washington, a nuclear aircraft carrier. I was honorably discharged in 2003 and tried my hand at civilian life for about a year. It didn't take too well, so I decided to try my hand at Army life. I enlisted as a 31E, a correction specialist [prison guard]. I spent three years on active duty stationed at the Fort Sill Regional Corrections Facility, where I attained the rank of staff sergeant. Again I was honorably discharged and tried my hand at civilian life. It lasted about five months before I was kicking down the door of the National Guard looking for the first flight to a combat zone. I enlisted under the "try one" option with a military police unit out of Smyrna, Tenn., the 269th Military Police Company. If it hadn't been for the professional and dedicated soldiers and NCOs of Third Platoon (and a select few others from other various platoons), I fear I might have lost my mind and my life. I'm 29 years old. I am a freshman at the University of Massachusetts, and I'm learning to be a civilian. And it's hard.

***

Sand and Other Enemies

The wind blew for two days straight. The cool air touched my face and whispered memories of sleeping in the park—Centennial Park in Nashville, a place my girlfriend and I would go when money was tight and things made sense. We would lie around the steps of the reconstructed Parthenon and I would watch her study until my eyes got sick of it and threw sleep in my face. It was lovely. It was a place that wasn't here.

Pleasure is a fragile thing here. Like a small mouse, it scrambles quickly from the open and into a small hole under the stairs and is gone. Weeks would pass before I would see it again. All the half-fake laughter and joy wasn't enough to convince that little mouse that this was a safe place, and I don't blame it for being too cautious.

I watched as the sky crawled away like a wounded thing, dragging behind it a burning orange I did not yet know. The sand fell like locusts from the once blue palette, and the gentle breeze I once loved became my enemy.

I hid in my room trying to avoid the sand that moved and hung like mist. All missions were canceled. I pissed in empty bottles and blew cigarette smoke through a crack in the door. My roommate and I entertained ourselves with games he had taught me. Marry, f--k, and murder was his favorite. You had to pick three women, one you would marry, one you would f--k, and one you would murder. I preferred rummy.

The sand wouldn't stop coming. It devoured my concept of time. I scrutinized a.m. and p.m. as the sun stood watch over us constantly; ruthless and hard-toed, it punished us. Perception was reality, and reality was negotiable. In spite of the hands on my watch spinning like helicopter rotors, time stood still. It was space travel. It was a time capsule. It was freeze-dried meat. I was jerky.

This dreadful dirt found its way in and settled on everything. It was the consistency of baby powder but as pleasant as poison. I slept in it. I ate off it. I drank from it. I even brushed my teeth with it, this inescapable sand.

Then we got the word, and I knew now why the sand came. "LT was shot and killed"—that's what we were told as we all gathered in the room designated for nothing but bad news, the chapel. It was silent as our boss, a man well into his 50s, choked on his words and told us what had happen. He cried openly, and I hated him for it. The droplets of salty grief slid from the corners of his eyes and ran down and under and up and over every wrinkle and crease of his stubbly, pitted face as he knelt on his cracking old knees, sobbing and weak. I wanted him to be tall and soulless. I wanted his eyes to be black marbles. That would make this whole thing seem less important, less real. But he was a scared and hurt old man, and sometimes he cried. Now he cried.

He finished speaking and asked that we all pray for the lieutenant and his family. He looked pitifully up at the room of soldiers, brave men and women with rifles and grenades, and found us all looking desperately for something on the floor. Our eyes fixed on anything but his. It was obvious that he wanted someone to lead us in prayer, but no one spoke. I thought for a minute that it should be me. But I didn't. I wasn't strong. My faith was as small as a pinhead in that room.

Faith had left this place long before, though. The chapel. The f--king chapel. Tell someone that you're going to the chapel to talk to your first sergeant and watch as they desperately try to distance themselves from you and your impending misery. Soldiers didn't come here to meet with God anymore. Soldiers came here to sleep. They came here to hide from work. They came here to throw dice and play dominoes. Right in the center of the room stood a shoddy homemade poker table with a half-finished game; one hand displayed three deuces on the river card. "What a s--tty hand to lose to," I thought, proof that God was nowhere in this building.

I'm home now, and LT is still dead, and I feel cheated. I expected to see his face everywhere, like in the stories and the movies, but I don't. I just see faces. I carry tainted concepts of happiness in my head. I smell diesel and I smile. My girlfriend wakes me to tell me that I'm having a bad dream and I reluctantly agree with her before I lie back down and quickly try to fall back asleep in a hurry not to lose my place. My therapist asks me what's wrong and I struggle to explain: I miss it.

Now the wind touches my cheeks and I think of that place, a place that isn't here. It whispers, quietly, always reminding me, always following me. It warns me that the sand is coming. I whisper back, "You can stay, wind. But the sand can go to hell."

Submitted by John Ubaldi of Sacramento, Calif.

September 11 is a day I will remember forever, just like most Americans. My first reaction to those horrific scenes that were replayed over and over on the television was sadness and anger at the same time. Like the generation who rushed to the recruiting office after Pearl Harbor, I couldn't wait to call my reserve unit and volunteer for active duty.

Before I deployed, I was employed at a political consulting firm in Sacramento, Calif., and informed my employer that I was heading off to war. Volunteering for active duty would forever change my life, and for that matter, my family's. I had no idea where I would be heading or where I would end up. My first deployment was to Afghanistan in 2002, almost six months after U.S. forces went into that troubled country.

While I was stationed there, I saw firsthand the suffering of the people, and when I visited an orphanage in an outlying village, I was appalled at the magnitude of their suffering. When I returned to the base, I made contact with my church and helped organize a humanitarian aid project, which resulted in sending more than 20,000 backpacks full of school supplies to a girls' school, recently renovated by a U.S. Army Civil Affairs unit. The school originally was to hold 800 girls, but 3,000 children showed up.

Submitted by Bill Buratto of Thousand Oaks, Calif.

I served as a medical laboratory technician for the 91st EVAC Hospital in Chu Lai, Vietnam, in 1970 and 1971. The mission of the hospital was to triage and treat casualties, stabilizing the most severely wounded so they could be evacuated to a rear hospital.

I remember going on rounds one afternoon to draw blood from patients. I approached the bed of a young quad amputee (he had stepped on a mine) and there was a nurse with a field phone holding the handset to his ear. As I got closer, I realized he was talking to his wife back in the States. He was very upbeat, telling her he was fine and that he'd be home soon and everything would be OK. I was struck by his positive attitude, wondering how I would react if I were in his position.

I don't know what happened to him, nor the thousands of young men we treated. But I do know that the resiliency of the human spirit displayed by these courageous young men has had a positive impact on my life. Like a lot of Vietnam vets, I came home, got my life back on track, and with each passing year the memories fade. But even now, 40 years later, when things aren't going my way, I remember that brave young soldier on the phone and draw inspiration and resolve from that brief encounter.

Submitted by Spc. Joseph M. McGlaughlin, who served in Iraq from 2006 to 2008.

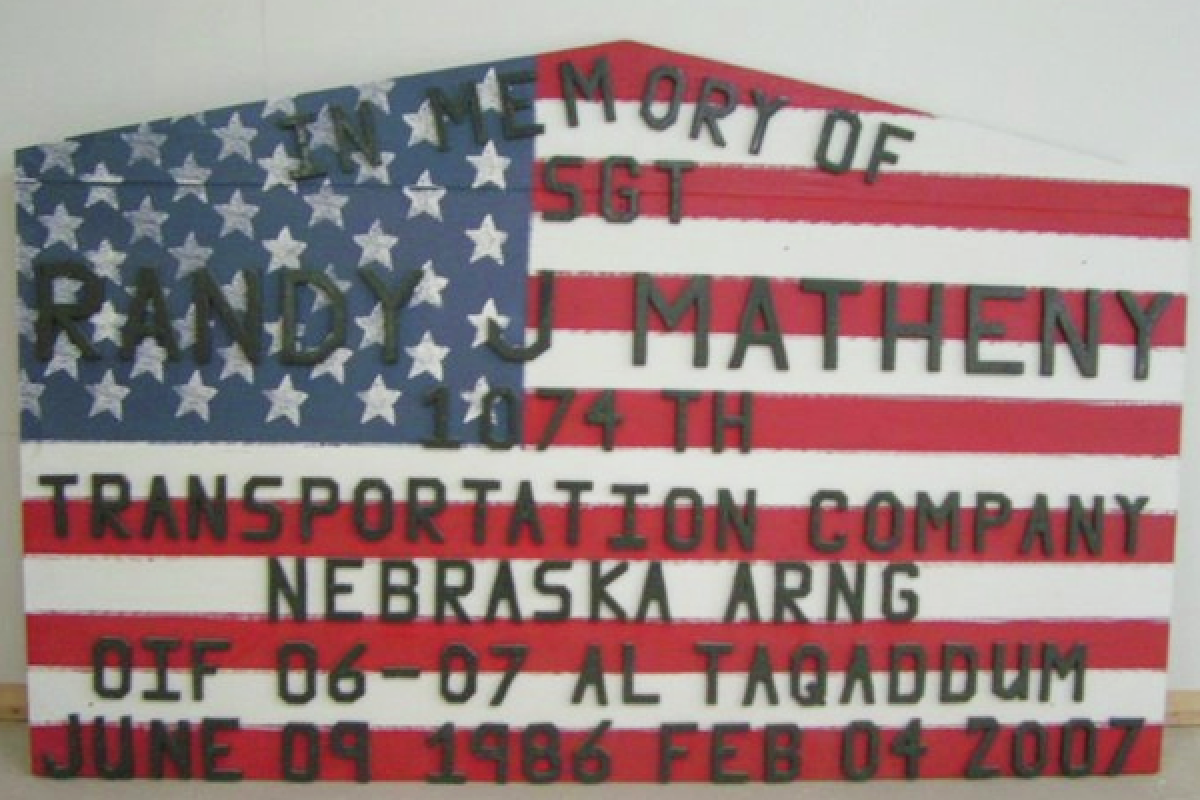

This picture was taken of a memorial to a 20-year-old soldier and friend. I did not know him well, and he did not know me all that well. We passed and exchanged hellos on our way to the smoking area, and maybe to and from the showers a few times, but he watched my back and I watched his. He was killed Feb. 4, 2007, on some highway 6,000 miles away from his home. The convoy was hit by insurgents; his vehicle was struck by an RPG round (rocket-propelled grenade). The unit he was in was in charge of protecting our convoys, and they did one hell of a job.

I was asked by an NCO in my company to draw up and paint the flag while the NCO made the letters. Once the NCO was done with the letters, I mapped out a flag on a piece of plywood, and found a sponge to cut into a star shape to use on the blue field. Getting paint in Iraq was not easy; I think we mixed a few colors to get the blue. Once it was completed, we presented it to his unit. They loved it. His unit decided it would look great mounted to the entrance of the MWR [building] that the units had built. We mounted it, and our first sergeant had a fit—I am guessing because he didn't get the glory for presenting or mounting it—and we were ordered to remove it. I have since found out that after we left that base, the soldier's unit had the memorial mounted to the MWR anyway, and it is still there to this day. I took this picture so he would forever be in my heart and soul. He will be missed greatly.

Submitted by Richard L. Albeen, of Leonia, N.J.

The Unsung Hero

A Veterans Day Thought

Sometimes, all too often, we forget the unsung heroes.

The unsung hero is not he who storms the enemy machine-gun emplacement and single-handedly overcomes those opponents who are decimating his comrades.

The unsung hero is not he who successfully drops his bomb payload upon the enemy and destroys their manufacturing capability or their transportation network.

The unsung hero is not he who is adulated and honored upon his return from the conflict and feted and honored by the politicians and bedecked with medals and ribbons.

The unsung hero is actually much more common than the heroes of the popular media and, sadly, much less known.

The unsung hero is the man who shelters his family during a blitz of soldiers intent upon killing everyone in their path. The one who hides and feeds his family to the best of his ability and runs into the path of the warriors to distract them from his wife and children and parents, and then dies at their hands, knowing he has done all he can to protect those whom he loves more than himself.

The unsung hero is he who works behind the lines, in the guise of one of the conquered, to engineer the downfall of the enemy who has unjustly occupied his country, enslaved his population, and hoisted the flag of hatred and death over his land.

The unsung hero is he who fights on in obscurity, not caring about medals and honors and recognition, not caring about whether he will live or die, but hoping only that his determination may help end the conflict a bit sooner and restore freedom to the land of his forefathers and his family and his offspring.

The unsung hero is he who will never surrender, never give up, and will fight on until victory or death decides his fate.

To all those unsung heroes past and present, we the living salute you, and honor you as we would any and all such heroes who believe in freedom, resist the imposition of tyranny, and fight on through the darkness and uncertainty of battle because of your beliefs.

To all such heroes, we give you the ultimate praise and adulation: our sincere thanks and undying appreciation.

This is the highest honor we can bestow, and it will last far longer than any dangling piece of metal and fabric we can place around your neck.

Because, unlike metal and fabric, our love and appreciation will never wither, but only become stronger over time.

Wear it proudly, for you have truly earned it.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.