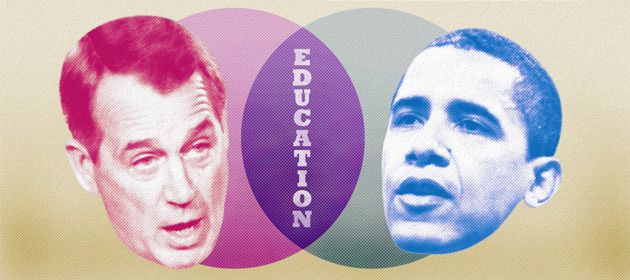

Washington can seem like a Venn diagram where the two circles—Republicans and Democrats—will never touch. But on the issue of education reform, the two parties may be able to come together. The Republican agenda of reform—imposing standardized test-based accountability for schools and teachers and fostering competition among schools—has been embraced and aggressively promoted by the Obama administration. President George W. Bush's signature achievement on this front, No Child Left Behind, has been due for renewal since 2007. Democrats are gearing up to pass a revised version of the law, possibly as soon as next year, and they think this is one issue where Republicans will work with them.

When the law was passed in 2001, it was a rare instance of bipartisanship in the polarized Bush era. Leading liberals Sen. Ted Kennedy and Rep. George Miller of California supported it, as did current House Speaker-in-waiting Rep. John Boehner, who at the time was chairman of the Education and Labor Committee. There was broad agreement that the educational system was failing to give each child an equal chance at success: there was too big a gap between the outcomes for children from low-income families and everyone else, and between white and nonwhite children. NCLB set out to solve the problem by comparing the performance of students at the same school from different backgrounds on standardized tests. Schools that had too low a percentage of disadvantaged students passing got access to federal help, such as money for dropout prevention, and continued failure meant that the students could transfer to better schools. In the years since it was passed, NCLB has drawn criticism from the left, especially educators, for being an overly blunt instrument, and on the right for intruding on local schools. Many teachers, and some parents, worry that the law has yielded unintended consequences, such as "teaching to the test," and good schools being identified as failing for not doing well enough on just one metric. (For example, a school in a growing suburban area might get an influx of immigrants and then be identified as failing for having too low a percentage of nonnative English speakers for their grade level in reading).

The name "No Child Left Behind" itself has become politically burdensome, especially among liberals who were turned off by the law's association with Bush and complained that it was underfunded. (NCLB was the politically catchy name of the 2001 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, or ESEA, the longstanding law that governs federal aid to schools, so the law will be revised under that less controversial name.) But the basic purpose—to measure educational performance and intervene when schools are truly failing—is still widely accepted. Among the mainstream education leaders in both parties, there seems to be mutual agreement that the law should be revised to keep the popular parts of NCLB, such as the way it breaks out data for different demographics of students, while scaling back its reach.

Reauthorization still won't be simple, thanks to the Tea Party and its goal of limiting the reach of the federal government. Some Republicans who rode to victory on the movement's wave went so far as to call for abolishing the Department of Education. And it's not only Republican newcomers who have rejected Bush's legacy of "compassionate conservatism" that his education-reform efforts were meant to signify. Even some Republicans who supported NCLB at the time did so reluctantly. They were corralled into supporting their party's president, though many had been on record opposing the Department of Education's existence. "Republicans went along on NCLB holding their noses," says Mike Petrilli, executive vice president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a right-leaning educational think tank, who worked in the Bush Education Department. Just a few years earlier the Republican Congress had opposed similar, less ambitious, reforms proposed by President Clinton. In the years after NCLB, says Petrilli, "many Republicans on Capitol Hill quickly had buyer's remorse."

But a deal is possible because both sides want to limit the scope of the law. Teachers' unions, especially the more doctrinaire National Education Association (NEA), are unhappy with the way that NCLB has been overly broad in its remediation of schools that fail by only one of the bill's many metrics. "We want to make sure the federal government doesn't overreach and become the principal of each school," says Kim Anderson, the NEA's government-relations director. "The new Congress may be more receptive to local-control arguments." The other major national teachers' union, the American Federation of Teachers, says it supports the goals of NCLB but has complained that "it requires schools and districts to meet arbitrary and unreasonable benchmarks." Conservatives want the government to intrude upon fewer schools. So, the interests on both sides can be satisfied by modifying the law so that it falls on fewer schools and does so more carefully.

In fact, the two sides are already talking. Education Secretary Arne Duncan says he has been regularly discussing ESEA reauthorization with the "Big Eight"—that's the education wonk term for the leaders of the relevant committees in both parties. Congressional staffers in both parties worked through the August recess on it. "They say how refreshing those meetings are," says Duncan, "that they wish they could work [so cooperatively] on other issues." Duncan says he expects Congress to introduce legislation "within the [2011] calendar year." Of course, Duncan was making the same prediction about ESEA at the beginning of 2010. Like a lot of important issues, it got delayed. Sen. Tom Harkin, the Iowa Democrat, who chairs the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, is even more optimistic, saying, "I hope to have [a bill through the committee] by summer." Harkin says every major education bill in his 25 years on the committee has been bipartisan and that he has strong working relationships with the committee's top two Republicans—ranking member Mike Enzi of Wyoming and former education secretary Lamar Alexander.

Harkin concedes that the rest of the Republican caucus is a different matter, and not only in the House, where they will be in the majority, but in the Senate, where procedural moves by a determined individual or minority can block action on almost anything. "What's going to be the position of these new senators who are just coming in and finding they have the power to stop things? Will their colleagues in their party say it is 'good rhetoric' to play to your audience but we've got to pass legislation? That's the $64,000 question." If the Senate Republican leadership's recent acquiescence to Tea Party demands that they promise not to pass any earmark spending in the next Congress is any indication, they might not act. Republicans, after all, just saw multiple incumbents get chased out of primaries or knocked off by right-wing insurgents. If they pass a new version of NCLB, even if they drop the name and curtail its impact, they could be targeted for voting to stick the federal government in the sensitive area of local public education.

But because bipartisan agreement on any complicated legislation is hard to come by these days, the two parties might just punt. Instead of reauthorizing ESEA and overhauling the entire law and its multitude of federal education programs, Congress might deal with just the overreach problem. Rather than improving the way schools are assessed, Congress would simply limit the number of schools affected. "NCLB is going to identify half of America's schools next year as failing to make adequate progress," says Frederick Hess, director of education-policy studies at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. "That irritates parents and educators. Congress is good at responding to that kind of frustration, but not enough to drive a big bill. The way Congress deals with annoyance is to make it go away." At least for a little while.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.