Four months before Rosa Parks refused to vacate her bus seat to a white man in 1955, she attended a retreat at the Highlander center in Tennessee, where she took a workshop alongside blacks and whites on school desegregation. More than a half century later, the Highlander center is still training soldiers in the fight for equal rights. Only now the battleground has shifted. Last January, four dozen gay and lesbian activists gathered for a center retreat overlooking the Smoky Mountains to get inspiration on how they could show—not just tell—America that their rights are being violated.

But how? There are no "heterosexuals only" Woolworth counters where gays and lesbians can protest segregation; even Woolworth itself is long gone from the U.S. "We needed to create the urgency and critical mass to stop the injustice towards our community," says Robin McGehee, a mother of two and cofounder of the civil-disobedience group that was formed during those five days in Tennessee, called GetEQUAL. "What are our lunch-counter images?"

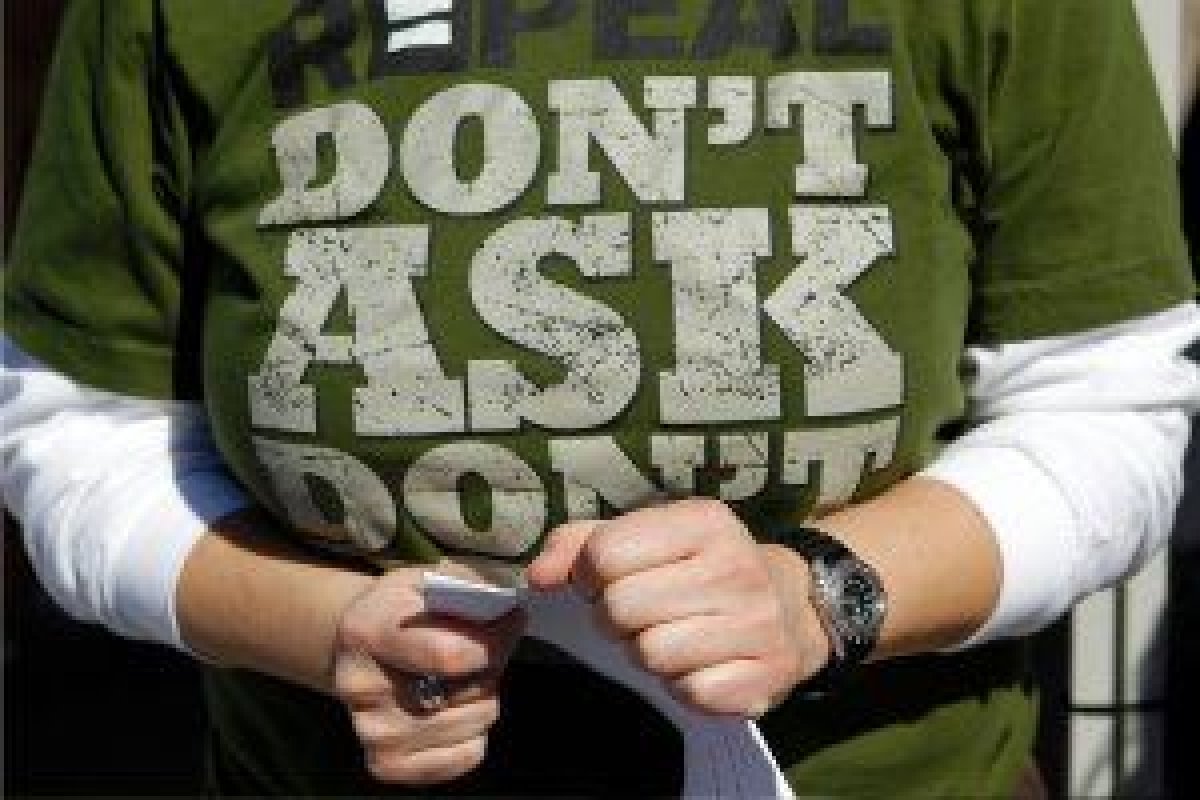

As the fight over same-sex marriage and "don't ask, don't tell" rages in the courts, Congress, and the media, gay activists and their allies are invoking the language and imagery of the civil-rights battles of a half century ago. And their efforts are changing the tenor of the debate. Sen. Joe Lieberman, calling for repeal of "don't ask, don't tell," told a Connecticut reporter earlier this month that the fight for gay rights is the new "front lines" of the civil-rights movement. When President Obama included protections for gays and lesbians in federal hate-crime legislation earlier this year, the Associated Press called it "the biggest expansion of the civil-rights-era law in decades." And at last week's federal appellate-court hearing in San Francisco on same-sex marriage, one of the judges pointedly asked whether California voters, whose 2008 passage of Proposition 8 stripped gays of the right to marry, were entitled to reinstate school segregation. "How is this different?" Judge Michael Daly Hawkins asked the attorney defending the measure. Legal heavyweights Ted Olson and David Boies, representing the pro-gay-marriage side, wrote in their plaintiffs' brief that the case tests the proposition whether gays and lesbians "should be counted as 'persons' under the 14th Amendment or whether they constitute a permanent underclass ineligible for protection under that cornerstone of our Constitution." The 14th Amendment removed the clause once embedded in the Constitution that slaves equaled three fifths of a person.

The rhetoric has inspired gays and lesbians. But it has also galvanized their opponents, who say homosexuals are fighting for "special rights," not civil rights. Brian Brown of the National Organization for Marriage says of same-sex matrimony: "It's not a civil right, it's a civil wrong"—one that will diminish the religious freedom of those who consider homosexuality sinful. The "special rights" argument was reflected in the Pentagon's report this month on "don't ask, don't tell." "Throughout the force, rightly or wrongly, we heard both subtle and overt resentment towards 'protected groups' of people and the possibility that gay men and lesbians could, with repeal, suddenly be elevated to a special status," the report found.

Gays and lesbians "may want to cast their fight in civil-rights terms, and a lot of people are buying it. But not the faith community and especially not the black community," says Bishop Harry Jackson, whose Hope Christian Church has a flock of 3,000 in the Washington, D.C., area. Indeed, some 70 percent of African-Americans voted yes on California's Prop 8, and exit polls found similar levels of opposition among blacks for a marriage initiative in Florida that same year. After the Washington, D.C., City Council last year approved gay marriage in the District, Jackson joined forces with the National Organization for Marriage in petitioning the U.S. Supreme Court to allow voters to decide on overturning the law. "Many African-Americans believe gays are discriminated against, but they don't believe marriage is a civil-rights issue," says Jackson, who says his father was threatened at gunpoint in the 1950s by a state trooper while working on a voter-registration drive. "There are issues of acceptance, but there is no back of the bus; there are no lynchings." There is also the ongoing debate as to whether homosexuality is an immutable trait or a choice. "It's not immutable," says Jackson. "And it's not an externally observable characteristic unless you want to flaunt it."

Underlying the resentment among many African-Americans is the belief that gays and lesbians can "pass" in straight, white America, and therefore enjoy advantages blacks never could because of their skin color. For example, Jackson is quick to say that gay people are "disproportionately well paid"—even though the data don't support this assumption. A study by UCLA's Williams Institute and the University of Massachusetts suggests that the lack of access to marriage benefits and workplace protections means gay and lesbian families are actually more likely to be poor than heterosexual ones. Get-EQUAL's McGehee, who like several other key organizers of the group grew up in a blue-collar family that saw its share of struggles, acknowledges that many gay people do have the "luxury" of appearing to blend in. "It makes me wonder if this is one reason why we've been struggling since the Stonewall riots of 1969 and before to acquire equal rights."

The opposition in the black community to equating gay rights with the civil-rights movement is far from universal. Last week, during the gay-marriage appeals in California, the Rev. Jesse Jackson called for African-Americans to support gay marriage. "To those that believe in and fought for civil rights, that marched to end discrimination and win equality, you must not become that which you hated," he said. Julian Bond, chairman emeritus of the NAACP and a veteran of the civil-rights movement, serves on the advisory committee of the group sponsoring the Prop 8 lawsuit. "Disturbingly, African-Americans are more homophobic than others. But it is not a 'special right' to be free of discrimination," he says. While some blacks may be threatened by the perception that the civil-rights movement is being co-opted by white people, Bond says "they should be happy others are imitating the movement they are so proud of."

The conflicted feelings of the black community are perhaps best illustrated by the split in the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s family. His widow, Coretta Scott King, spent many years before her death urging African-Americans to honor her late husband by recognizing gay rights as a civil-rights issue. Yet Alveda King, the reverend's niece, spoke out last August at a rally of the National Organization for Marriage, saying she hailed from "a long line of Christian soldiers," and that despite current attacks on traditional marriage, it "remains the guard against human extinction." She told NEWSWEEK that while her heart is "touched by the plight of humans," there is a line that shouldn't be crossed when it comes to civil rights. "My cousin, the Rev. Bernice King, has said that she knows in her sanctified soul that her father did not take a bullet for same-sex marriage."

The gay-rights movement has its martyrs, too: Matthew Shepard, the 21-year-old gay man murdered near Laramie, Wyo., in 1998, and, more recently, Tyler Clementi, the 18-year-old Rutgers freshman who committed suicide in September after he was harassed for being gay. But the fight for equal rights remains mostly in the courtrooms and on op-ed pages, not on the streets like the civil-rights battles of the 1950s and '60s. That's what the activists trained at the Highlander center are attempting to change. Earlier this year Get-EQUAL shut down traffic on Las Vegas Boulevard in an attempt to prod Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid to schedule a vote on the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, which would ban unequal treatment in the workplace on the basis of sexual orientation or identity—a protection lacking in more than half of U.S. states. (Polling shows that about 61 percent of heterosexual Americans assume incorrectly that such protections already exist.) That vote hasn't yet been scheduled. Nonetheless, it was a big moment for the gay community, which hasn't seen a concerted civil-disobedience effort since ACT UP took to the streets in the late 1980s to demand that the government and drug companies do more to fight AIDS.

Working with recognized figures in the gay-rights fight like Dan Choi, a former Army lieutenant who was discharged under "don't ask, don't tell," the members of GetEQUAL can often be found at the Washington, D.C., home of political strategist Paul Yandura, strategizing sit-ins and other nonviolent protests. Before their first "action" in March, when Choi and a fellow ousted soldier handcuffed themselves to the White House gates, the protesters were busy writing phone numbers on their arms and stomachs so they would have them at the ready for their designated phone call once arrested. In jail, Choi and the fellow discharged soldier recited passages from King's "Letter From a Birmingham Jail" to keep each other inspired.

Even as they invoke the civil-rights struggle, GetEQUAL's members are trying to be politic. Philanthropist Jonathan Lewis and his family, who have funneled a half-million dollars to create and support GetEQUAL's efforts, says gays and lesbians are absorbing lessons and inspiration from the civil-rights movement, not taking away its importance. "Our movement is not the same," he says. "Yes, it's not life or death every day like the civil-rights movement was," says Michelle Wright, who is African-American and became involved in GetEQUAL after coming out last year. "But it's still discrimination, and therefore it's wrong." Now she and her fellow activists just need to get the rest of America to see it that way. So they will continue searching, however long it takes, for their movement's own lunch-counter image.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.