Ever had goosebumps or felt euphoric chills when listening to a piece of music? If so, your brain is reacting to the music in the same way as it would to some delicious food or a psychoactive drug such as cocaine, according to scientists.

The experience of pleasure is mediated in all these situations by the release of the brain's reward chemical, dopamine, according to results of experiments carried out by a team led by Valorie Salimpoor of McGill University in Montreal, Canada, which are published today in Nature Neuroscience.

Music seems to tap into the circuitry in the brain that has evolved to drive human motivation – any time we do something our brains want us to do again, dopamine is released into these circuits. "Now we're showing that this ancient reward system that's involved in biologically adaptive behaviours is being tapped into by a cognitive reward," said Salimpoor.

She said music provided an intellectual reward, because the listener has to follow the sequence of notes to appreciate it. "A single tone won't be pleasurable in isolation. However, a series of single tones arranged in time can become some of the most pleasurable experiences that humans have ever reported. That's amazing because it suggests that somehow our cerebral cortex is following these tones over time and there must be a component of build-up, anticipation, expectation."

In the experiment, participants chose instrumental pieces of music that gave them goosebumps, but which had no specific memories attached to them. Lyrics were banned because the researchers did not want their results confounded by any associations participants might have had to the words they heard.

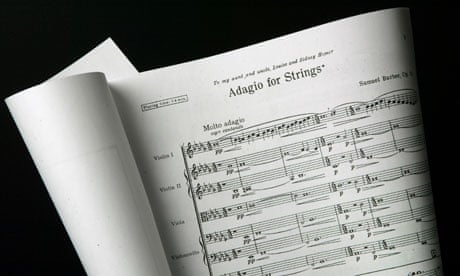

The pieces chosen ranged from classical to rock, punk and electronic dance music. "One piece of music kept coming up for different people – Barber's Adagio for Strings," said Salimpoor. It was the favourite classical piece and a remix of the tune was the most popular in the dance, trance and techno genres.

As the participants listened to their music, Salimpoor's team measured a range of physiological factors including heart rate and increases in respiration and sweating. She found that the participants had a 6-9% relative increase in their dopamine levels when compared with a control condition in which the participants listened to each other's choices of music. "One person experienced a 21% increase. That demonstrates that, for some people, it can be really intensely pleasurable," she said.

In previous studies with psychoactive drugs such as cocaine, Salimpoor said relative dopamine increases in the brain had been above 22%, while a relative increase of up to 6% was experienced when eating pleasurable meals.

Salimpoor and her colleagues concluded: "If music-induced emotional states can lead to dopamine release, as our findings indicate, it may begin to explain why musical experiences are so valued. These results further speak to why music can be effectively used in rituals, marketing or film to manipulate hedonistic states. Our findings provide neurochemical evidence that intense emotional responses to music involve ancient reward circuitry and serve as a starting point for more detailed investigations of the biological substrates that underlie abstract forms of pleasure."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion