If Martin Luther King Jr. were alive today—he would have turned 82 last week—he would in all likelihood be in Arizona, marching against the forces of violence. Not that he'd be particularly welcome there. Arizona, of course, is the state whose former governor, Evan Mecham, made headlines back in the 1980s defending the word "pickaninny" and scrapping the state's observance of the MLK holiday. King's views on the Second Amendment would be suspect in many parts of this heat-packin' state—a place where firearm ownership, entwined with a certain strain of reactionary patriotism, has in some quarters reached the level of High Creed.

A surprising number of Arizonans love their gun shows, their firing ranges, their border posses, their libertarian civics classes, their Ayn Rand novels, their Wild West laws allowing them to carry concealed weapons pretty much anywhere they've got a hankering to go. Tombstone, with its O.K. Corral, is a national shrine dedicated to the blunt grandeur of the shootout. In Palin-speak, Arizona doesn't need to reload—it carries a 33-round clip.

King would be in Arizona for many reasons, but the main one is this: throughout his career, he was absolutely committed to nonviolence as both a philosophy and a tactic. He did not believe in bodyguards, certainly not armed ones. No one in his entourage was allowed to carry a gun or nightstick or any other weapon. The very concept of arming oneself was odious to him—it violated his Gandhian principles. He wouldn't even let his children carry toy guns. In an almost mystical sense, he believed nonviolence was a more potent force for self-protection than any weapon. He understood the threats against him but refused to let them alter the way he lived.

Far from being timid, King's pacifism had a confrontational edge. His marches often attracted violence and served as powerful magnets for turmoil and hate. That was their purpose, in fact—to expose through choreographed drama a social evil for all to see, preferably with cameras rolling.

So everywhere King went, the threat, and often the reality, of violence loomed. His grace and courage in the teeth of this hostility were otherworldly, and they're something I think about every MLK Day. His house was firebombed. He was punched in the face by a Nazi. He was hit in the head with a rock. In 1958, a psychotic black woman stabbed him with a letter opener while he was signing books at a Harlem department store. Though King nearly died in that incident—the blade came within a hair's breadth of his aorta—he refused to press charges. The day before he was killed, King's plane to Memphis received a bomb threat. The possibility of death was such a constant in his life that he adopted a futile acceptance of it. "If someone wants to kill me," he said in Memphis, "there's nothing I can do about it."

Sadly, the events in Arizona last week carry many odd hints and echoes of the events in the spring of 1968 that culminated in King's death at the hands of James Earl Ray. Then, as now, the country was fighting an intractable and apparently interminable war against a hard-to-find enemy on the other side of the planet—a conflict that had drained the nation's coffers and left the populace fatigued and paranoid. Then, as now, the airwaves seethed with reactionary speech. Then, as now, gun sales were going up, up, up.

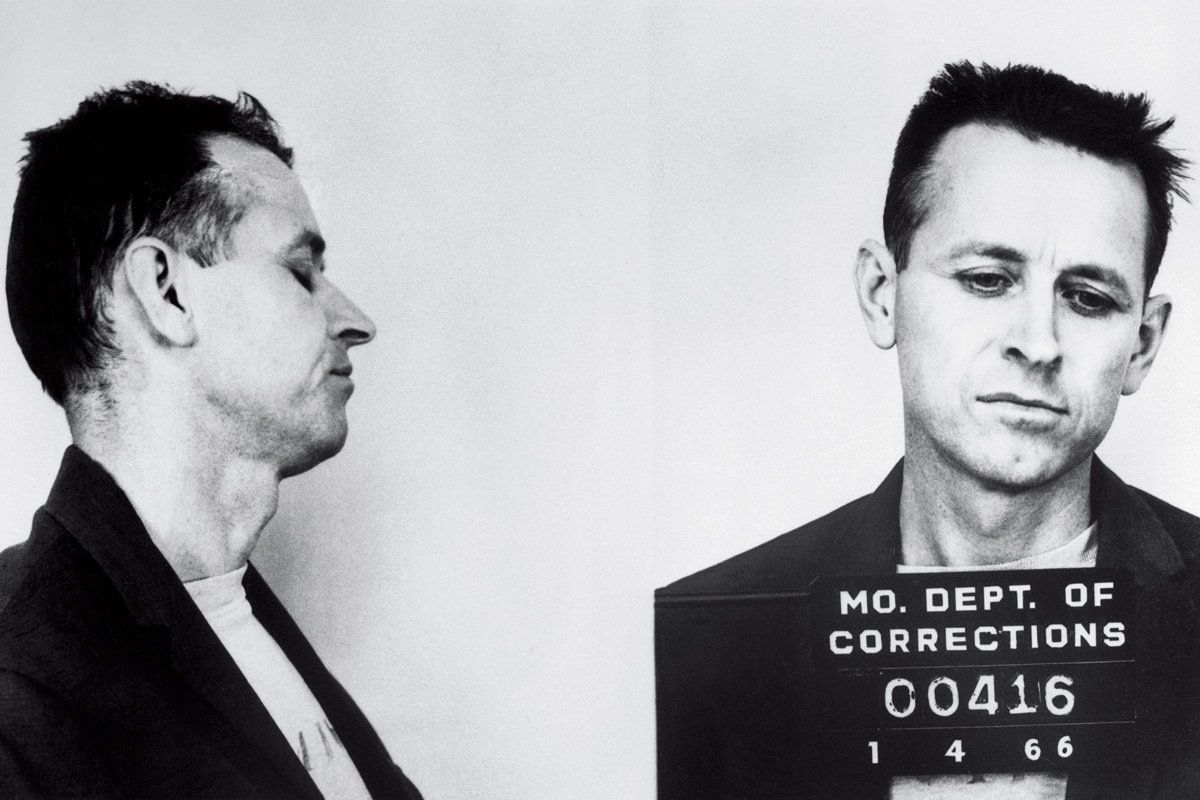

Ray, the Illinois-born career criminal who was convicted in 1969 and served the rest of his life in prison, was not a psychotic lunatic in the way that Jared Lee Loughner apparently is. But he was certainly a deeply nutty and disturbed man—in ways that said much about American society in the late 1960s. A lone wolf with a permanent smirk, Ray yearned for a purpose and a goal. He was an empty vessel of the culture, filling his cheerless hours with self-help advice, national fads, and the constant natter of the news. In the months before the assassination, he took dancing lessons, got a nose job, underwent hypnosis, enrolled in a locksmithing course, dabbled in the porn business, investigated the immigration policies of Rhodesia, shopped for rifles, and campaigned for the racist presidential candidate George Wallace. A welter of jumbled stimuli flooded into what was essentially an incoherent identity: on a profound level, Ray didn't know who he was.

Certainly the culture of hate—omnipresent in 1968, just as it is now—was complicit in Ray's crime. George Wallace may or may not have understood the far-reaching consequences of the statements he was putting out in 1968. He wasn't literally saying, "Go kill King." Yet Wallace and other segregationists created an inflamed environment in which a confused but also ambitious man like Ray could think it was permissible, perhaps even noble, to murder King. The signals Ray was picking up enabled him to believe that society would smile on his crime.

What a sordid tradition of violence we have in our country—and what an alarming record of assassinations and assassination attempts. Perhaps it's the dark flip side of our extraordinary personal freedoms. The ease with which a person can move about this huge country, melt into communities, develop new identities—and buy high-powered weapons, no questions asked—has proved a formula for national heartache. Ray and now Loughner are just two in a long line of American nobodies who've left their permanent stain on our history.

Why did he do it? That's still the toughest question of all with Ray—and no doubt will be with Loughner, too. It's hard to find a clean rational explanation for what is, fundamentally, an insane act of violence. Because Ray lied all the way to his grave, we may never know the real answer, or if there even was one. I've come to think that he was guided not by a single motivation but by a cluster of submotivations that spun in the blender of his unsettled mind. Yes, he was a racist. Yes, he wanted money. Yes, he was a troubled sociopath—his skewed thoughts intensified by a lifetime of using amphetamines. But what really motivated him, I'm convinced, was a desire for recognition. Herein lies a paradox: though he spent his criminal career striving for anonymity, he desperately wanted the world to know he existed. He longed to do something bold and lasting. Like a certain deranged young man in Tucson last week, Ray imagined the best way to leave his mark was to gun down someone young, eloquent, and charismatic.

I am not one of those people who believe that MLK achieved more in martyrdom than he could have if he'd lived: imagine what a guiding influence he could have on the world were he still among us. If we can't have him in Arizona today, we can at least call on his spirit. And we must.

Sides is the author of Hellhound on His Trail, a narrative history of the King assassination, out in paperback this March from Anchor.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.