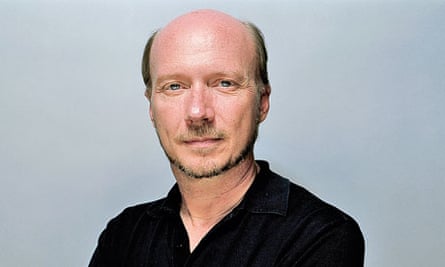

On 19 August 2009, Tommy Davis, the chief spokesperson for the Church of Scientology International, received a letter from the film director and screenwriter Paul Haggis. "For 10 months now I have been writing to ask you to make a public statement denouncing the actions of the Church of Scientology of San Diego," Haggis wrote. Before the 2008 elections, a staff member at Scientology's San Diego church had signed its name to an online petition supporting Proposition 8, which asserted that the state of California should sanction marriage only "between a man and a woman". The proposition passed. As Haggis saw it, the San Diego church's "public sponsorship of Proposition 8, which succeeded in taking away the civil rights of gay and lesbian citizens of California – rights that were granted them by the Supreme Court of our state – is a stain on the integrity of our organisation and a stain on us personally. Our public association with that hate-filled legislation shames us." Haggis wrote, "Silence is consent, Tommy. I refuse to consent." He concluded, "I hereby resign my membership in the Church of Scientology."

Haggis was prominent in both Scientology and Hollywood, two communities that often converge. Although he is less famous than certain other Scientologists, such as Tom Cruise and John Travolta, he had been in the organisation for nearly 35 years. Haggis wrote the screenplay for Million Dollar Baby, which won the Oscar for Best Picture in 2004, and he wrote and directed Crash, which won Best Picture the next year. Davis, too, is part of Hollywood society: his mother is Anne Archer, who starred in Fatal Attraction and Patriot Games.

In previous correspondence with Davis, Haggis had demanded that the church publicly renounce Proposition 8. "I feel strongly about this for a number of reasons," he wrote. "You and I both know there has been a hidden anti-gay sentiment in the church for a long time. I have been shocked on too many occasions to hear Scientologists make derogatory remarks about gay people, and then quote LRH in their defence." The initials stand for L Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology, whose extensive writings and lectures form the church's scripture. Haggis related a story about Katy, the youngest of three daughters from his first marriage, who lost the friendship of a fellow Scientologist after revealing that she was gay. The friend began warning others, "Katy is '1.1'." The number refers to a sliding Tone Scale of emotional states that Hubbard published in a 1951 book, The Science Of Survival. A person classified "1.1" was, Hubbard said, "Covertly Hostile" – "the most dangerous and wicked level" – and he noted that people in this state engaged in such things as casual sex, sadism and homosexual activity. Hubbard's Tone Scale, Haggis wrote, equated "homosexuality with being a pervert". (Such remarks don't appear in recent editions of the book.)

In his resignation letter, Haggis explained to Davis that, for the first time, he had explored outside perspectives on Scientology. He had read a recent exposé in a Florida newspaper, the St Petersburg Times, which reported, among other things, that senior executives in the church had been subjecting other Scientologists to physical violence. Haggis said he felt "dumbstruck and horrified", adding, "Tommy, if only a fraction of these accusations are true, we are talking about serious, indefensible human and civil-rights violations."

Online, Haggis came across an appearance that Davis had made on CNN in May 2008. The presenter John Roberts asked Davis about the church's policy of "disconnection", in which members are encouraged to separate themselves from friends or family members who criticise Scientology. Davis responded, "There's no such thing as disconnection as you're characterising it."

In his resignation letter, Haggis said, "We all know this policy exists." Haggis reminded Davis that a few years earlier his wife had been ordered to disconnect from her parents, "because of something absolutely trivial they supposedly did 25 years ago when they resigned from the church". Haggis continued, "To see you lie so easily, I am afraid I had to ask myself: what else are you lying about?"

Haggis forwarded his resignation to more than 20 Scientologist friends, including Archer, Travolta and Sky Dayton, the founder of EarthLink. "People started calling me, saying, 'What's this letter Paul sent you?'" Davis says. A St Petersburg Times exposé had inspired a fresh series of hostile reports on Scientology, which has long been portrayed in the media as a cult. And, given that some well-known Scientologist actors were rumoured to be closeted homosexuals, Haggis's letter raised awkward questions about the church's attitude toward homosexuality. Most important, Haggis wasn't an obscure dissident; he was a celebrity, and the church, from its inception, has depended on celebrities to lend it prestige. To Haggis's friends, his resignation from the Church of Scientology felt like a very public act of betrayal. They were surprised, angry and confused. "'Destroy the letter, resign quietly' – that's what they all wanted," Haggis says.

Last March, I met Haggis, 57, in New York. He was in the editing phase of his latest movie, The Next Three Days, a thriller starring Russell Crowe, and preparing for two events later that week: a preview screening in New York and a charitable trip to Haiti.

Haggis was born in 1953, and grew up in London, Ontario, where his father, Ted, had a construction company. He decided at an early age to be a writer, but after leaving school, he drifted, hanging out with hippies and drug dealers.

He fell in love with Diane Gettas, a nurse, and they began sharing a one-bedroom apartment. One day in 1975, when he was 22, Haggis was walking to a record store when a young man pressed a book into his hands. "You have a mind," the man said. "This is the owner's manual." The book was Dianetics: The Modern Science Of Mental Health, by L Ron Hubbard, which was published in 1950. By the time Haggis began reading it, Dianetics had sold about 2.5m copies. Today, according to the church, that figure has reached more than 21m.

Haggis opened the book and saw a page stamped with the words "Church of Scientology". He had heard about Scientology a couple of months earlier, from a friend who had called it a cult. The thought that he might be entering a cult didn't bother him. In fact, he said, "it drew my interest. I tend to run toward things I don't understand."

At the time, Haggis and Gettas were having arguments; the Scientologists told him that taking church courses would improve the relationship. "It was pitched to me as applied philosophy," Haggis says. He and Gettas took a course together and, shortly afterwards, became Hubbard Qualified Scientologists, one of the first levels in what the church calls the Bridge to Total Freedom.

The Church of Scientology says its purpose is to transform individual lives and the world. "A civilisation without insanity, without criminals and without war, where the able can prosper and honest beings can have rights, and where man is free to rise to greater heights, are the aims of Scientology," Hubbard wrote. Scientology postulates that every person is a Thetan – an immortal spiritual being that lives through countless lifetimes. Scientologists believe that Hubbard discovered the fundamental truths of existence, and they revere him as "the source" of the religion.

In 1955, a year after the church's founding, a publication urged Scientologists to cultivate celebrities: "It is obvious what would happen to Scientology if prime communicators benefiting from it would mention it." At the end of the 60s, the church established its first Celebrity Centre, in Hollywood. (There are now satellites in Paris, Vienna, Düsseldorf, Munich, Florence, London, New York, Las Vegas and Nashville.) Over the next decade, Scientology became a potent force in Hollywood. In many respects, Haggis was typical of the recruits from that era, at least among those in the entertainment business. Many of them were young and had quit school in order to follow their dreams, but they were also smart and ambitious. The actor Kirstie Alley, for example, left the University of Kansas in 1970 to get married. Scientology, she says, helped her lose her craving for cocaine. "Without Scientology, I would be dead," she has said.

In 1975, the year that Haggis became a Scientologist, John Travolta, a high school dropout, was making his first movie, The Devil's Rain, when an actor on the set gave him a copy of Dianetics. "My career immediately took off," he told a church publication. "Scientology put me into the big time." The testimonials of such celebrities have attracted many curious seekers. In Variety, Scientology has advertised courses promising to help aspiring actors "make it in the industry".

Haggis and I travelled together to LA, where he was presenting The Next Three Days to the studio. During the flight, I asked how high he had gone in Scientology. "All the way to the top," he said. Since the early 80s, he had been an Operating Thetan VII, which was the highest level available when he became affiliated with the church. (In 1988, a new level, OT VIII, was introduced to members; it required study at sea, and Haggis declined to pursue it.) He had made his ascent by buying "intensives" – bundled hours of auditing, at a discount rate. "It wasn't so expensive back then," he said.

David S Touretzky, a computer-science professor at Carnegie Mellon University, has done extensive research on Scientology. (He is not a defector.) He estimates that the coursework alone now costs nearly $300,000 and, with the additional auditing and contributions expected of upper-level members, the cumulative cost may exceed half a million dollars. (The church says there are no fixed fees, adding, "Donations requested for 'courses' at the Church of Scientology begin at $50 and could never possibly reach the amount suggested.")

Haggis and I spoke about some events that had stained the reputation of the church while he was a member. For example, there was the death of Lisa McPherson, a Scientologist who died after a mental breakdown, in 1995. She had crashed a car in Clearwater, Florida – where Scientology has its spiritual headquarters – and then stripped off her clothes and wandered naked down the street. She was taken to hospital, but, in the company of several other Scientologists, she checked out against doctors' advice. (The church considers psychiatry an evil profession.) McPherson spent the next 17 days being subjected to church remedies, such as doses of vitamins and attempts to feed her with a turkey baster. She became comatose, and died of a pulmonary embolism before church members finally brought her to the hospital. The medical examiner in the case, Joan Wood, initially ruled that the cause of death was undetermined, but she told a reporter, "This is the most severe case of dehydration I've ever seen." The state of Florida filed charges against the church. In February 2000, under withering questioning from experts hired by the church, Wood declared that the death was "accidental". The charges were dropped and Wood resigned.

Haggis said that, at the time, he had chosen not to learn the details of McPherson's death. "I had such a lack of curiosity when I was inside. It's stunning to me, because I'm such a curious person." His life was comfortable, he liked his circle of friends, and he didn't want to upset the balance. It was also easy to dismiss people who quit the church. As Haggis put it, "There's always disgruntled folks who say all sorts of things."

In 1977, Haggis and Diane Gettas got married and, shortly after, they drove to Los Angeles, where he got a job moving furniture. In 1978, Gettas gave birth to their first child, Alissa. Haggis was spending much of his time and money taking advanced courses and being audited, which involved the use of an electropsychometer, or E-Meter. The device, often compared in the press to a polygraph, measures the bodily changes in electrical resistance that occur when a person answers questions posed by an auditor. ("Thoughts have a small amount of mass," the church contends in a statement. "These are the changes measured.") The Food and Drug Administration has compelled the church to declare that the instrument has no curative powers and is ineffective in diagnosing or treating disease.

Haggis found the E-Meter surprisingly responsive. The auditor often probed for what Scientologists call "earlier similars". Haggis explained, "If you're having a fight with your girlfriend, the auditor will ask, 'Can you remember an earlier time when something like this happened?' And if you do, then he'll ask, 'What about a time before that? And a time before that?'" Often, the process leads participants to recall past lives.

Although Haggis never believed in reincarnation, "I did experience gains. I think I did, in some ways, become a better person." Then again, he admitted, "I tried to find ways to be a better husband, but I never really did. I was still the selfish bastard I always was."

At night, Haggis wrote scripts on spec. He met Skip Press, another young writer who was a Scientologist, and they started hanging out with other aspiring writers and directors who were involved with Scientology. "We would meet at a restaurant across from the Celebrity Centre called Two Dollar Bill's," Press recalls. Haggis and a friend from this circle eventually got a job writing for cartoons, including Scooby-Doo and Richie Rich.

By now, Haggis had begun advancing through the upper levels of Scientology. The church defines an Operating Thetan as "one who can handle things without having to use a body or physical means".

"The process of induction is so long and slow that you really do convince yourself of the truth of some of these things that don't make sense," Haggis told me. Although he refused to specify the contents of OT materials, on the grounds that it offended Scientologists, he said, "If they'd sprung this stuff on me when I first walked in the door, I just would have laughed and left right away." But by the time Haggis approached the OT III material, he'd already been through several years of auditing. His wife was deeply involved in the church, as was his sister, Kathy. Moreover, his first writing jobs had come through Scientology connections. He was now entrenched in the community and had invested a lot of money in the programme. The incentive to believe was high.

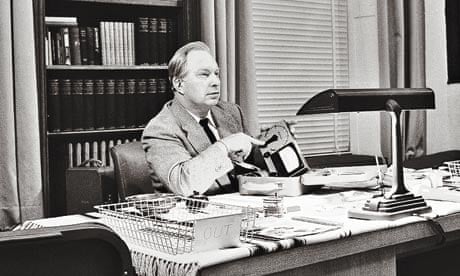

The many discrepancies between L Ron Hubbard's legend and his life have overshadowed the fact that he was a fascinating man. He was born in Tilden, Nebraska, in 1911. In 1933, he married Margaret Grubb, whom he called Polly; their first child, Lafayette, was born the following year. He visited Hollywood, and began getting work as a screenwriter, but much of his energy was devoted to publishing stories, often under pseudonyms, in pulp magazines such as Astounding Science Fiction.

During the second world war, Hubbard served in the US navy. He later wrote that he was gravely injured in battle and fully healed himself, using techniques that became the foundation of Scientology. After the war, his marriage dissolved, and he ended up in Los Angeles. He continued writing for the pulps, but he had larger ambitions. He began codifying a system of self-betterment, and set up an office where he tested his techniques on the actors, directors and writers he encountered. He named his system Dianetics.

The book, Dianetics, appeared in May 1950 and spent 28 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. Dianetics purports to identify the source of self-destructive behaviour – the "reactive mind", a kind of data bank that is filled with traumatic memories called "engrams". The object of Dianetics is to drain the engrams of their painful, damaging qualities and eliminate the reactive mind, leaving a person "Clear".

Dianetics, Hubbard said, was a "precision science". He offered his findings to the American Psychiatric Association and the American Medical Association, but was spurned; he subsequently portrayed psychiatry and psychology as demonic competitors. Scientists dismissed Hubbard's book, but hundreds of Dianetics groups sprang up across the US and abroad. The Church of Scientology was officially founded in Los Angeles in February 1954, by several devoted followers of Hubbard's work.

In 1966, Hubbard – who by then had met and married another woman, Mary Sue Whipp – set sail with a handful of Scientologists. The church says that being at sea provided a "distraction-free environment", allowing Hubbard "to continue his research into the upper levels of spiritual awareness". Within a year, he had acquired several ocean-going vessels. He staffed the ships with volunteers, many of them teenagers, who called themselves the Sea Organisation. Hubbard and his followers cruised the Mediterranean searching for loot he had stored in previous lifetimes. (The church denies this.)

The Sea Org became the church's equivalent of a religious order. The group now has 6,000 members, who perform tasks such as counselling, maintaining the church's vast property holdings and publishing its official literature. Sea Org initiates – some of whom are children – sign contracts for up to a billion years of service. They get a small weekly stipend and receive free auditing and coursework. Sea Org members can marry, but they must agree not to raise children while in the organisation.

As Scientology grew, it was increasingly attacked. In 1963, the Los Angeles Times called it a "pseudoscientific cult". The church attracted dozens of lawsuits, largely from ex-parishioners. In 1980, Hubbard disappeared from public view. Although there were rumours that he was dead, he was actually driving around the Pacific Northwest in a motor home. He returned to writing science fiction and produced a 10-volume work, Mission Earth, each volume of which was a bestseller. In 1983, he settled quietly on a horse farm in Creston, California.

In 1985, with Hubbard in seclusion, the church faced two of its most difficult court challenges. In Los Angeles, a former Sea Org member, Lawrence Wollersheim, sought $25m for "infliction of emotional injury". He claimed he had been kept for 18 hours a day in the hold of a ship docked in Long Beach, and deprived of adequate sleep and food.

That October, the litigants filed OT III materials in court. Fifteen hundred Scientologists crowded into the courthouse, trying to block access to the documents. The church, which considers it sacrilegious for the uninitiated to read its confidential scriptures, got a restraining order, but the Los Angeles Times obtained a copy of the material and printed a summary.

"A major cause of mankind's problems began 75m years ago," the Times wrote, when the planet Earth, then called Teegeeack, was part of a confederation of 90 planets under the leadership of a despotic ruler named Xenu. "Then, as now, the materials state, the chief problem was overpopulation." Xenu decided "to take radical measures". Surplus beings were transported to volcanoes on Earth, and bombed, "destroying the people but freeing their spirits – called Thetans – which attached themselves to one another in clusters." The Times account concluded, "When people die, these clusters attach to other humans and keep perpetuating themselves."

The jury awarded Wollersheim $30m. (Eventually, an appellate court reduced the judgment to $2.5m.) The secret OT III documents remained sealed, but the Times' report had already circulated widely, and the church was met with derision all over the world.

The other court challenge in 1985 involved Julie Christofferson-Titchbourne, a defector who argued that the church had falsely claimed that Scientology would improve her intelligence, and even her eyesight. In a courtroom in Portland, she said that Hubbard had been portrayed to her as a nuclear physicist; in fact, he had failed to graduate from George Washington University. As for Hubbard's claim that he had cured himself of grave injuries in the second world war, the plaintff's evidence indicated that he had never been wounded in battle. Witnesses for the plaintiff testified that in one six-month period in 1982, the church transferred millions of dollars to Hubbard through a Liberian corporation. The church denied this, and said that Hubbard's income was generated by his book sales.

The jury sided with Christofferson-Titchbourne, awarding her $39m. Scientologists streamed into Portland to protest. They carried banners advocating religious freedom and sang We Shall Overcome. Scientology celebrities, including Travolta, showed up. Haggis, who was writing for the NBC series The Facts Of Life at the time, came and was drafted to write speeches. "I wasn't a celebrity – I was a lowly sitcom writer," he says. He stayed for four days.

The judge declared a mistrial, saying that Christofferson-Titchbourne's lawyers had presented prejudicial arguments. It was one of the greatest triumphs in Scientology's history, and the church members who had gone to Portland felt an enduring sense of kinship. (A year and a half later, the church settled with Christofferson-Titchbourne for an undisclosed sum.)

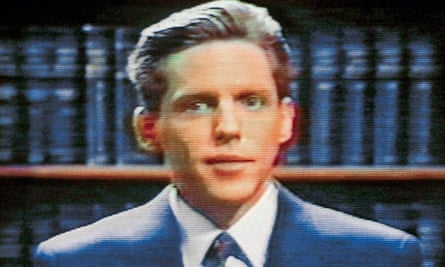

In 1986, Hubbard died, of a stroke, in his motor home. He was 74. Two weeks later, Scientologists gathered in the Hollywood Palladium for a special announcement. A young man, David Miscavige, stepped on to the stage. Short, trim and muscular, with brown hair and sharp features, Miscavige announced to the assembled Scientologists that for the past six years Hubbard had been investigating new, higher OT levels. "He has now moved on to the next level," Miscavige said. "It's a level beyond anything any of us ever imagined. This level is, in fact, done in an exterior state. Meaning that it is done completely exterior from the body. Thus, at 20:00 hours, the 24 of January, AD 36" – that is, 36 years after the publication of Dianetics – "L Ron Hubbard discarded the body he had used in this lifetime." Miscavige began clapping, and led the crowd in an ovation, shouting, "Hip hip hooray!"

Miscavige was a Scientology prodigy from the Philadelphia area. He claimed that, growing up, he had been sickly and struggled with bad asthma; Dianetics counselling had dramatically alleviated the symptoms. As he puts it, he "experienced a miracle". He decided to devote his life to the religion. He had gone Clear by the age of 15, and the next year he dropped out of high school to join the Sea Org. He became an executive assistant to Hubbard, who gave him special tutoring in photography and cinematography. When Hubbard went into seclusion, in 1980, Miscavige was one of the few people who maintained close contact with him. With Hubbard's death, the curtain rose on a man who was going to impose his personality on an organisation facing its greatest test, the death of its charismatic founder. Miscavige was 25 years old.

When Haggis finally reached the top of the Operating Thetan pyramid, he expected that he would feel a sense of accomplishment, but he remained confused and unsatisfied.

He was a workaholic, and as his career took off, he spent less and less time with his family. He and his wife began a divorce battle that lasted nine years and, in 1997, a court determined that Haggis should have full custody of the children.

His daughters were resentful. "I didn't even know why he wanted us," Lauren says. The girls demanded to be sent to boarding school, so Haggis enrolled them at the Delphian School, which uses Hubbard's educational system, called Study Tech. By the time she graduated, Lauren says, she had scarcely ever heard anyone speak ill of Scientology.

Alissa found herself moving away from the church and did not speak to her father for a number of years. When she was in her early 20s, she accepted the fact that, like her sister Katy, she was gay.

In 1991, as his marriage was crumbling, Haggis went to a Fourth of July party at the home of Scientologist friends. Deborah Rennard, who played JR's alluring secretary on Dallas, was at the party. Rennard had grown up in a Scientology household and joined the church herself at the age of 17. They became a couple, and married in June, 1997. A son, James, was born the following year.

Despite his growing disillusionment with Scientology, Haggis raised a significant amount of money for it, and made sizeable donations himself. The Church of Scientology had recently gained tax-exempt status as a religious institution, making donations, as well as the cost of auditing, tax-deductible. (Church members had lodged more than 2,000 lawsuits against the Internal Revenue Service, ensnaring the agency in litigation. As part of the settlement, the church agreed to drop its legal campaign.)

Over the years, Haggis estimates, he spent more than $100,000 on courses and auditing, and $300,000 on various Scientology initiatives. Rennard says she spent about $150,000 on coursework. Haggis recalls that the demands for donations never seemed to stop. "They used friends and any kind of pressure they could apply," he says. "I gave them money just to keep them from calling and hounding me."

Proposition 8 passed in November 2008. A few days after sending his resignation letter to Tommy Davis in February 2009, Haggis came home from work to find nine or 10 of his Scientology friends standing in his front yard. He invited them in to talk and referred them to the exposé in the St Petersburg Times that had so shaken him: The Truth Rundown. The first instalment had appeared in June 2009. Haggis had learned from reading it that several of the church's top managers had defected in despair. Marty Rathbun had once been inspector general of the church's Religious Technology Centre, and had also overseen Scientology's legal-defence strategy, reporting directly to Miscavige. Amy Scobee had been an executive in the Celebrity Centre network. Mike Rinder had been the church's spokesperson, the job now held by Davis. One by one, they had disappeared from Scientology, and it had never occurred to Haggis to ask where they had gone.

The defectors told the newspaper that Miscavige was a serial abuser of his staff. "The issue wasn't the physical pain of it," Rinder said. "It's the fact that the domination you're getting – hit in the face, kicked – and you can't do anything about it. If you did try, you'd be attacking the COB" – the chairman of the board. Tom De Vocht, a defector who had been a manager at the Clearwater spiritual centre, told the paper that he, too, had been beaten by Miscavige; he said that from 2003 to 2005, he had witnessed Miscavige striking other staff members as many as 100 times. Rathbun, Rinder and De Vocht all admitted that they had engaged in physical violence themselves. "It had become the accepted way of doing things," Rinder said. Scobee said that nobody challenged the abuse because people were terrified of Miscavige. Their greatest fear was expulsion: "You don't have any money. You don't have job experience. You don't have anything. And he could put you on the streets and ruin you."

Much of the alleged abuse took place at the Gold Base, a Scientology outpost in the desert 80 miles south-east of Los Angeles. Miscavige has an office there, and for decades the base's location was unknown even to many church insiders. According to a court declaration filed by Rathbun in July, Miscavige expected Scientology leaders to instil aggressive, even violent, discipline. Rathbun said that he was resistant, and that Miscavige grew frustrated with him, assigning him in 2004 to the Hole – a pair of double-wide trailers at the Gold Base. "There were between 80 and 100 people sentenced to the Hole at that time," Rathbun said in the declaration. "We were required to do group confessions all day and all night."

The church claims that such stories are false: "There is not, and never has been, any place of 'confinement'… nor is there anything in Church policy that would allow such confinement."

According to Rathbun, Miscavige came to the Hole one evening and announced that everyone was going to play musical chairs. Only the last person standing would be allowed to stay on the base. He declared that people whose spouses "were not participants would have their marriages terminated". The St Petersburg Times noted that Miscavige played Queen's Bohemian Rhapsody on a boom box as the church leaders fought over the chairs, punching each other and, in one case, ripping a chair apart.

De Vocht, one of the participants, says the event lasted until 4am: "It got more and more physical as the number of chairs went down." Many of the participants had long been cut off from their families. They had no money, no credit cards, no telephones. According to De Vocht, many lacked a driver's licence or a passport. Few had any savings or employment prospects. As people fell out of the game, Miscavige had aeroplane reservations made for them. He said that buses were going to be leaving at 6am. The powerlessness of everyone else in the room was nakedly clear.

Davis told me that a musical chairs episode did occur. He explained that Miscavige had been away from the Gold Base for some time, and when he returned he discovered that in his absence many jobs had been reassigned. The game was meant to demonstrate that even seemingly small changes can be disruptive to an organisation – underscoring an "administrative policy of the church". The rest of the defectors' accounts, Davis told me, was "hoo-ha": "Chairs being ripped apart, and people being threatened that they're going to be sent to far-flung places in the world, plane tickets being purchased, and they're going to force their spouses – and on and on and on. I mean, it's just nuts!"

The church provided me with 11 statements from Scientologists, all of whom said that Miscavige had never been violent. The church characterises Scobee, Rinder, Rathbun, De Vocht and other defectors I spoke with as "discredited individuals" who were demoted for incompetence or expelled for corruption; the defectors' accounts are consistent only because they have "banded together to advance and support each other's false 'stories'".

After reading the St Petersburg Times series, Haggis tracked down Marty Rathbun, who says Haggis was shocked by their conversation. "The thing that was most troubling to Paul was that I literally had to escape," Rathbun told me. (A few nights after the musical chairs incident, he got on his motorcycle and waited until a gate was opened for someone else; he sped out and didn't stop.) Haggis called several other former Scientologists he knew well. One said he had escaped from the Gold Base by driving his car through a wooden fence. Still others had been expelled or declared Suppressive Persons. Haggis asked himself, "What kind of organisation are we involved in where people just disappear?"

At his house, Haggis finished telling his friends what he had learned. "I directed them to certain websites," he said, mentioning Exscientologykids.com. The stories on the site, of children drafted into the Sea Org, appalled him. "They were 10 years old, 12 years old, signing billion-year contracts – and their parents go along with this?" Haggis told me. "Scrubbing pots, manual labour – that so deeply touched me. My God, it horrified me!"

Many Sea Org volunteers find themselves with no viable options for adulthood. If they try to leave, the church presents them with a "freeloader tab" for all the coursework and counselling they have received; the bill can amount to more than $100,000. "Many of them actually pay it," Haggis said. "They leave, they're ashamed of what they've done, they've got no money, no job history, they're lost, they just disappear." In what seemed like a very unguarded comment, he said, "I would gladly take down the church for that one thing."

The church says it adheres to "all child labour laws", and that minors can't sign up without parental consent; the freeloader tabs are an "ecclesiastical matter" and are not enforced through litigation.

Haggis's friends came away from the meeting with mixed feelings. This would be the last time most of them spoke to him.

In the days after, church officials and members came to his office, distracting his producing partner, Michael Nozik, who is not a Scientologist. "Every day, for hours, he would have conversations with them," Nozik told me.

"I listened to their point of view, but I didn't change my mind," Haggis says, noting that the Scientology officials, "became more livid and irrational."

In October 2009, Rathbun called Haggis and asked if he could publish the resignation letter on his blog. "You're a journalist, you don't need my permission," Haggis said, although he asked Rathbun to excise parts relating to Katy's homosexuality.

Haggis says he didn't think about the consequences of his decision: "I thought it would show up on a couple of websites. I'm a writer, I'm not Lindsay Lohan." Rathbun got 55,000 hits on his blog that afternoon. The next morning, the story was in newspapers around the world.

At the time Haggis was doing his research, the FBI was conducting its own investigation. Agents Tricia Whitehill and Valerie Venegas interviewed former church and Sea Org members. One was Gary Morehead, who had been the head of security at the Gold Base; he left the church in 1996. In February 2010, he told Whitehill he had developed a "blow drill" to track down Sea Org members who left Gold Base. In 13 years, he estimates, he and his security team brought more than 100 Sea Org members back to the base. When emotional, spiritual or psychological pressure failed to work, Morehead says, physical force was sometimes used. (The church says that blow drills do not exist.)

Whitehill and Venegas worked on a special task force devoted to human trafficking. The California penal code lists several indicators: signs of trauma or fatigue; being afraid or unable to talk; owing a debt to one's employer. Those conditions echo the testimony of many former Sea Org members.

Sea Org members who have "failed to fulfil their ecclesiastical responsibilities" may be sent to one of the church's several Rehabilitation Project Force locations. Defectors describe them as punitive re-education camps. In California, there is one in Los Angeles; until 2005, there was one near the Gold Base, at a place called Happy Valley. Bruce Hines, a defector turned research physicist, says he was confined to RPF for six years, first in LA, then in Happy Valley. He recalls that the properties were heavily guarded and that anyone who tried to flee would be subjected to further punishment. "In 1995, when I was put in RPF, there were 12 of us," Hines said. "At the high point, in 2000, there were about a 120." Some members have been in RPF for more than a decade, doing manual labour and extensive spiritual work. (Davis says that Sea Org members enter RPF by their own choosing and can leave at any time; the manual labour maintains church facilities and instils "pride of accomplishment".)

Defectors also talked to the FBI about Miscavige's luxurious lifestyle. The law prohibits the head of a tax-exempt organisation from enjoying unusual perks or compensation; it's called inurement. Davis refused to disclose how much money Miscavige earns, and the church isn't required to do so, but Headley and other defectors suggest that Miscavige lives more like a Hollywood star than like the head of a religious organisation – flying on chartered jets and wearing custom-made shoes. (The church denies this characterisation and "vigorously objects to the suggestion that Church funds inure to the private benefit of Mr Miscavige.") By contrast, Sea Org members typically receive $50 a week.

Last April, John Brousseau, who had been in the Sea Org for more than 30 years, left the Gold Base and drove to south Texas to meet Marty Rathbun. He was unhappy with Miscavige, his former brother-in-law, whom he considered "detrimental to the goals of Scientology". At 5.30 one morning, he was leaving his motel room when he heard footsteps behind him. It was Tommy Davis; he and 19 church members had tracked Brousseau down. Brousseau locked himself in his room and called Rathbun, who alerted the police; Davis went home without Brousseau.

In a deposition given in July, Davis said no when asked if he had ever "followed a Sea Organisation member that has blown [fled the church]". Under further questioning, he insisted that he was only trying "to see a friend of mine". Davis now calls Brousseau "a liar".

Brousseau says his defection caused anxiety, in part because he had worked on a series of special projects for Tom Cruise. Cruise says he was introduced to the church in 1986 by his first wife Mimi Rogers (she denies this), and Miscavige has called him "the most dedicated Scientologist I know". When Cruise married Katie Holmes in 2006, Miscavige was his best man.

In 2005, Miscavige showed Cruise a Harley-Davidson motorcycle he owned. Brousseau recalls, "Cruise asked me, 'God, could you paint my bike like that?'" Brousseau also says he helped customise a Ford Excursion SUV that Cruise owned. "I was getting paid $50 a week," he recalls. "And I'm supposed to be working for the betterment of mankind." Both Cruise's attorney and the church deny Brousseau's account.

Miscavige's official title is chairman of the board of the Religious Technology Centre, but he dominates the entire organisation. His word is absolute, and he imposes his will even on some of the people closest to him. According to Rinder and Brousseau, in June 2006, while Miscavige was away from the Gold Base, his wife, Shelly, filled several job vacancies without her husband's permission. Soon afterwards, she disappeared. Her current status is unknown. Davis told me, "I definitely know where she is", but he wouldn't disclose where that is.

In late September, Davis and other church representatives met with me. In response to nearly a thousand queries, the Scientology delegation handed over 48 binders of supporting material. Davis attacked the credibility of Scientology defectors, whom he calls "bitter apostates". We discussed the allegations of abuse lodged against Miscavige. "The only people who will corroborate are their fellow apostates," Davis said. He produced affidavits from other Scientologists refuting the accusations, and noted that the tales about Miscavige always hinged on "inexplicable violent outbursts". Davis said, "One would think that if such a thing occurred – which it most certainly did not – there'd have to be a reason."

I had wondered about these stories as well. While Rinder and Rathbun were in the church, they had repeatedly claimed that allegations of abuse were baseless. Then, after Rinder defected, he said Miscavige had beaten him 50 times. Rathbun has confessed that in 1997 he ordered incriminating documents destroyed in the case of Lisa McPherson, the Scientologist who died of an embolism. If these men were capable of lying to protect the church, might they not also be capable of lying to destroy it? Davis later claimed that Rathbun is in fact trying to overthrow Scientology's current leadership and take over the church. (Rathbun now makes his living by providing Hubbard-inspired counselling to other defectors, but says he has no desire to be part of a hierarchical organisation. "Power corrupts," he says.)

Twelve other defectors told me that they had been beaten by Miscavige, or had witnessed Miscavige beating other church staff members. Most of them, such as John Peeler, noted that Miscavige's demeanour changed "like the snap of a finger".

At the meeting, Davis and I also discussed Hubbard's war record. His voice filling with emotion, he said that if it was true that Hubbard had not been injured, then "the injuries that he handled by the use of Dianetics procedures were never handled, because they were injuries that never existed; therefore, Dianetics is based on a lie; therefore, Scientology is based on a lie." He concluded, "The fact of the matter is that Mr Hubbard was a war hero."

After filing a request with the National Archives in St Louis, we obtained what archivists assured us were Hubbard's complete military records – more than 900 pages. Nowhere in the file is there mention of Hubbard's being wounded in battle.

Since leaving the church, Haggis has been in therapy, which he has found helpful. He has learned how much he blames others for his problems, especially those who are closest to him. "I really wish I had found a good therapist when I was 21," he said.

On 9 November, The Next Three Days premiered in Manhattan. After the screening, I asked Haggis if he felt that he had finally left Scientology. "I feel much more myself, but there's a sadness," he admitted. "If you identify yourself with something for so long, and suddenly you think of yourself as not that thing, it leaves a bit of space." He went on, "It's not really the sense of a loss of community. Those people who walked away from me were never really my friends."

I once asked Haggis about the future of his relationship with Scientology. "These people have long memories," he told me. "My bet is that, within two years, you're going to read something about me in a scandal that looks like it has nothing to do with the church." He thought for a moment, then said, "I was in a cult for 34 years. Everyone else could see it. I don't know why I couldn't."