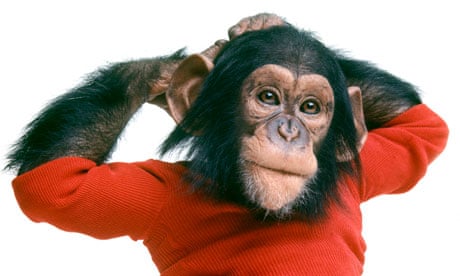

Whether he's zooming past in a pushchair, perched on a lavatory seat or getting a little too intimate with a passing cat, it's impossible not to be charmed by Nim the chimpanzee. Nim Chimpsky, to give him his full title, was born at the Institute for Primate Studies in Norman, Oklahoma, in the early 70s. Highly intelligent, he was chosen to be the subject of a language experiment at Columbia University, called Project Nim, that aimed to discover whether or not chimpanzees could use grammar to create sentences if they were taught sign language and nurtured in a similar environment to human children. His name is a pun on Noam Chomsky, the linguist who theorised that language is unique to humans, which the experiment hoped to disprove.

Nim's life story is told in Project Nim, a new documentary by Man on Wire director James Marsh, described by the New York Times as a "probing, unsettling study of primate behaviour". He has used archive footage, photographs and interviews with those who cared for Nim to create a tribute to the chimp and his turbulent life.

"Nim behaves in a way that is normal for a chimpanzee, but he's in a human world. He's in the wrong context and that becomes his tragedy," Marsh says, drinking his third espresso of the morning on a drizzly Sunday in Edinburgh. "The nature-versus-nurture debate clearly was part of the intellectual climate of that time and remains an interesting question – how much we are born a certain way, as a species and as individuals. In Nim's case, he has a chimpanzee's nature and that nature is an incredibly forceful part of his life. What [the scientists] try to do is inhibit his nature and you see the results in the story.

"I was intrigued because I hadn't seen that in a film before, the idea of telling an animal's life from cradle to grave using the same techniques as you would use for a human biography."

Marsh admits that conveying Nim's experiences was tough. "The overlap between the species [human and chimpanzee] does involve emotions. But at the same time I was very wary of those from the get-go. I felt that Nim's life had been blighted by people projecting on to him human qualities and trying to make him something that he wasn't."

Marsh, 48, fresh from the Oscar success of Man on Wire, was looking for a new documentary subject when his producer came across The Chimp Who Would Be Human, Elizabeth Hess's book about Project Nim, which he thought had potential.

"I want to find a dramatic way into the story, which is part of the story. So in Man on Wire's case it was Philippe [Petit] having a nightmare the night before, and he wakes up in feverish excitement and fear. In Project Nim's case, it's the original sin, the abduction of Nim [from his mother], that sets the whole thing off."

Another reason Marsh decided to make Project Nim was the rich seam of human drama that unfolded around the chimp.

"The human behaviour we see flushed out by Nim's presence in our world was very interesting, and revealed something about us," he says. "I can't always be sure about what Nim is thinking and feeling because he's a chimpanzee, but I've got a better grip on what humans are doing. Well, I hope I do!"

In his interviews, Marsh has teased out the sexual relationships, conflicts and rivalries between Nim's carers, including Stephanie LaFarge, Nim's first surrogate mother, Professor Herbert Terrace, head of Project Nim at Columbia University, Laura Ann Petitto, a research student, and Bob Ingersoll, who befriends Nim when he returns to the research facility in Oklahoma.

"Nim had these intense relationships with people, which became very important episodes in their lives. Everyone who I approached agreed to be in the film and spoke, I think, with great candour," Marsh says. "There was quite a lot of regret and guilt in some of the people involved and that came out in quite a confessional way in the interviews, which were long and very intense.

"For the women in particular, there were very complex feelings involved in their relationships with Nim, maternal feelings, powerfully so in Laura and Stephanie's case. So you're dealing with powerful memories and it's your job to give those memories the right context and to elicit them in a respectful way."

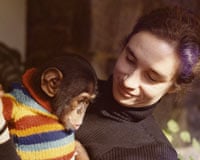

Young Nim, adorably clothed in outfits more suited to a toddler than a baby chimpanzee, seems perfectly designed to excite feelings of affection and protectiveness. At one point in the film, Stephanie LaFarge admits to breastfeeding Nim, as she did her other, human, children.

"But it's a mistake to think they're like us in our ways," Marsh warns. "Chimps seem to have emotions we recognise – they feel sorrow and sadness; they feel grief if they are bereaved; if they're on their own they get incredibly lonely; you can see that in Nim. But it's a mistake to think they are more like us than they are."

Marsh goes on to describe his impression of Nim. The chimp had a sweet and tactile side but could also be violent, messy and vicious. But as Marsh points out, that's what chimpanzees are like, that's how they behave. The only problem is that humans can't always understand or deal with it.

"An overlap that I find very interesting is the hedonistic side," he adds. "It seems hard-wired that chimpanzees like thrills and sensations and altered states. Nim likes to smoke pot and drink beer. But that's like us. Maybe it's hard-wired in us too. It seems to be hard-wired in me!"

Marsh has two children – they live with him and his wife in Copenhagen – and parenthood had a big impact on his decision to make the film.

"I'd seen my children acquire language, I'd seen them acquire two languages – they speak Danish and English. It was simple for them to have two languages on the go, all the time. Not a problem. So it does suggest that humans are utterly made for language. Nim was not.

"And if you have children, you soon understand that there's an embryonic personality from birth. You mess with that at your peril. You need to understand what your children are like, rather than try to impose your desires upon them. There's a fine line between letting them be what they are and making them responsible in the world, and that's definitely a theme that I brought to Nim, or some personal experience." He thinks parents will definitely respond to the portrayal of Nim's upbringing on screen in a unique way.

When I ask Marsh what he hopes audiences will take away from the film, he leaves it open. "I've made choices and selections that I think are true to the events of Nim's life. But I don't think I'm making overt judgments about people's behaviour. I think everyone in the film has reasons for doing what they do, which I respect. So the judgments, in a sense, are up to you."

The key players: Project Nim's human cast

PROJECT LEADER: Professor Herbert Terrace, Columbia University

"Terrace had a very simple question – can a chimpanzee create a sentence? And the word 'create' is the operative verb there. Are they endlessly inventive with language in the way we are? Do they use grammar? Do they organise words around a principle of syntax?

"His endgame was incredibly radical. It was, if I can give a chimpanzee language, I can empty the contents of his mind. He can tell me what he's thinking, how he sees the world. It would be a bit like being in touch with an alien from outer space!

"But his conclusion is they do not use language in that way, and I would not argue with that. He comes up against a very strong boundary between the species. Perhaps we can never know how a chimpanzee sees the world, or how a dog sees the world. We can make attributions, but those are very, very suspect.

"I don't know how he reacted to the film, though he wrote me an email saying it was well made but there was a deficiency in the science of it, and I wouldn't disagree with that.

"Up until now I think that Terrace had quite a privileged rendering of the story. He wrote his own book about Project Nim, and he's the person you would talk to about the science of the project and his conclusions. But I put his actions in the context of the people who were doing most of the work, and therefore looked at those power relations between him and women such as Laura Ann [Petitto] and Joyce [Butler], and how those played out.

"I didn't give him a privileged point of view, which he had at the time, because he was the most powerful figure in that experiment. In my telling of the tale he has an equal status with the other people, and that's how it should be."

FIRST MUM: Stephanie LaFarge, ex-student and former lover of Professor Terrace

"Nim's environment really should have been a jungle in Africa. But it wasn't. He was born in a cage in Oklahoma, in a breeding facility for chimpanzees. Very shortly afterwards, he was abducted from his mother. He was given to Stephanie LaFarge, to be brought up a nice brownstone on the Upper West Side of New York. The whole premise was that if you brought up a newborn primate of intelligence with humans, could you essentially inhibit his primate behaviour and give him human language?

"The LaFarges were a bohemian family. Comfortable. There were lots of children. Stephanie was an experienced mother. She brought him up for around 18 months, in her home, as if he were a human child, but Stephanie quickly understood that Nim's nature was way more powerful than anything we could do to inhibit it.

"When she first got him in her arms, he was tough and wiry already. Within a couple of months he could scoot around the house, and in a few more months he could climb the walls. And yet he had nappies and was vulnerable and needed to be fed. But very quickly, his physical attributes emerged. Though he wasn't a human baby he was certainly treated as one, and that's the whole idea, to find out if nurture of an alien species would make him like us. Does that work? Well, I think the answer is in the film.

"The tension that played out between her and Professor Terrace is about that. For the purposes of the experiment, he wanted Nim to be a sterile box being drilled with language. And she said that's against his nature, why don't we try to find some middle ground, but she didn't prevail, and he was taken away from her.

"You can scoff at some of Stephanie's methods and some of her actions, but I would not. I think that she was trying to get with what Nim is, as opposed to what others were trying to make him. I have a lot of time for her approach. You can laugh at giving him a beer or a puff on a joint, or letting him scoot around on a motorcycle. But at the same time that felt like it was more in his nature than putting him in a classroom and teaching him language. He embraced those things much more!"

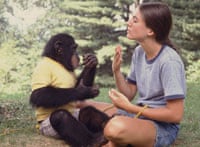

SECOND MUM: Laura Ann Petitto, research student, Columbia University

"Nim went from a nice big bohemian, Upper West Side brownstone to a huge mansion in Riverdale that Columbia University owned in the Bronx, where he continues to be taught to use sign language.

"His second human mother was Laura, only 18 at the time, extraordinarily young, but a very bright, capable woman. She then got, like Stephanie, embroiled emotionally with Professor Terrace. And that caused her complications.

"I'm not one to judge, but you feel she was in a very vulnerable position. She was 18 years of age, running this language experiment with a chimpanzee that increasingly began to test her and to attack her, and she was also embroiled in a relationship with a professor that perhaps was very unequal, in view of his position, and he was 20 years older than she was.

"Science has to involve detachment and empiricism and the collection of reproducible data, but if you ask a woman to bring up a chimpanzee, it involves their emotional life, and emotions can't be subject to the same kind of rational inquiry. That's the inherent problem of Project Nim; it's a scientific experiment that involves messy and volatile emotions – human emotions, and chimpanzee emotions, too."

TEACHER: Joyce Butler, research student

"The people who were most successful with Nim were the people who dominated him, which meant he knew his place and understood that this person was more powerful than he was. Joyce bit Nim's ear when he misbehaved and from then on their relationship progressed well.

"Nim wasn't always sweet, cute and kind. If you showed weakness in his presence then he exploited that; he would put you in your place in a violent and aggressive way, as you see in the story. So you couldn't be too kind to him, as he became an adolescent, because if you were he would not respect you.

"Unfortunately, or fortunately, the fact of the matter was he respected people who actually bit him and hit him. He responded to that. You can't hurt a chimpanzee. If you think it was wrong to whack him, you're making a mistake, actually. We shouldn't be sentimental about this, because he understood that language, if you can call it that."

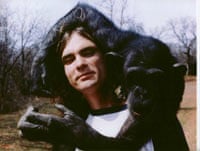

BEST FRIEND: Bob Ingersoll, research student at Institute for Primate Studies, Oklahoma

"I think Bob felt very sorry for Nim when the chimp returned to Oklahoma, and he began to give him certain freedoms. He was taken out from his cage, they'd go on these lovely walks together and they'd sign and communicate in a rich way, way beyond just the narrowness of the sign-language experiment, using verbal communication and body language. Nim also had recreational drugs at that point. Who could begrudge him those?

"Nim was Bob's friend. There's a kind of beauty in their relationship that I really cherish and wanted to show in the film. He accepted Nim for what he was. The best human relationships with animals come when you meet them halfway, when you're not saying: 'Be like us.' You're saying: 'You're like you, and I'm like me, let's find the middle ground.' I think Bob found that middle ground with Nim."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion