A 40-year-old man who was critically ill with heart failure has become the first person in Britain to be allowed home with an artificial heart.

Matthew Green, who is married and has a son, was given the all-clear to leave Papworth hospital near Cambridge after surgeons fitted the device in a six-hour operation last month.

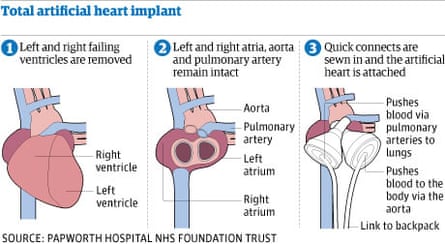

Doctors removed most of Green's heart before implanting the plastic device, which circulates blood around the body using two pumps powered by a unit Green wears in a 6kg (13lb) shoulder bag.

Green's departure from hospital went smoothly – apart from a brief wave of panic caused by an alarm sounding from his portable powerpack during a press conference with journalists. "It doesn't like it when I get nervous," he said.

Speaking of the operation, he added: "Before, I could barely feel my pulse, but now I've got a very strong heartbeat."

Green had been suffering from a condition called arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), a heart muscle disease that causes arrhythmia and heart failure and is recognised as a cause of sudden death in the young.

The disease, which is caused by genetic mutations that are passed down the family line, takes hold when healthy heart cells become detached from their neighbours and replaced by fat and scar tissue. Despite its name, the condition can destroy both of the main chambers of the heart.

Doctors offered Green the implant as a last resort when his health began to rapidly deteriorate. The artificial organ, known as a total artificial heart, is a temporary measure used to keep the most seriously ill patients alive until a matched donor heart becomes available.

More than 900 have been implanted in patients, mostly in the US and Europe, in some cases for several months. Papworth hospital is the only UK medical centre certified to implant the devices. The creation of the portable powerpack last year made it possible for patients to leave hospital after surgery.

"I want to thank all the wonderful staff at Papworth hospital who have been looking after me and who have made it possible for me to return home to my family," Green said.

"Two years ago, I was cycling nine miles to work and nine miles back every day but, by the time I was admitted to hospital, I was struggling to walk even a few yards.

"I am really excited about going home and just being able to do the everyday things that I haven't been able to do for such a long time, such as playing in the garden with my son and cooking a meal for my family."

The implant replaces heart valves and the two large ventricles that collect and pump blood around the body. According to the Arizona-based manufacturer, SynCardia, 60% of patients who are fitted with the device are able to walk more than 30 metres two weeks after surgery.

The transplant team, led by Steven Tsui, a consultant cardiothoracic surgeon and director of the transplant service at Papworth, had training in Paris before attempting the operation. The team was assisted by Latif Arusoglu, a transplant surgeon from Bad Oeynhausen, Germany, who has experience of fitting the devices.

Green said he was looking forward to returning to his wife, Gill, and five-year-old son, Dylan, at their home in London. In the long term, he hopes to return to his job as a scientist for a pharmaceutical company. "My movement will still be limited but at least I can return home to be with my family. That means the world to me," he said.

"My background as a research scientist meant I could understand how it worked and perhaps made me less nervous. But it's a miraculous bit of technology and it's given me my life back. I can't stress enough how important this development could be for people like me. The freedom to be at home and live something close to an ordinary life is important and will help with my recovery."

A spokeswoman for Papworth hospital said Green was the first patient to undergo the artificial heart operation at the centre. The device, which costs £100,000 plus £20,000 a year to maintain, is slightly larger than a normal human heart and can only be implanted into patients with large chest cavities.

Tsui said: "At any point, there may be as many as 30 people waiting for a heart transplant on our waiting list at Papworth, with one-third waiting over a year.

"Matthew's condition was deteriorating rapidly and we discussed with him the possibility of receiving this device because, without it, he may not have survived the wait until a suitable donor heart could be found for him.

"It would not be possible on all people but, when suitable, it is a medium-term solution which buys us time when looking for a transplant. We're delighted this has been a success and we are delighted Matthew and his family will be able to return to something close to normality."