Farmers have begun to turn away from organic food production in the face of waning interest from the big supermarkets.

The amount of land being converted to organic cultivation across the UK has dropped by two-thirds since 2007, according to statistics released by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, as falling sales of organic products mean fewer farmers are seeing a reason to change.

Sales of organic products fell by 5.9% in the UK last year, according to the Soil Association, from £1.8bn in 2009 to £1.7bn. That continued a decline from record sales of £2.1bn in 2008, and came amid rising food prices. The amount of organic poultry being produced has also fallen steadily.

But many farmers who have gone organic were defiant after publication of the latest figures, arguing that switching to greener methods has drastically cut their costs and that consumer interest is still strong, particularly when farmers can use sales routes other than big supermarket chains.

"There might be lots of farmers who think they can't afford to go organic, because they think the market is restricted, but if they looked into it they would find it can be cost-effective," said Ian Noble, who represents a 12-farm cooperative in south Devon growing organic vegetables. With little or no costs for fertilisers and pesticides, and – at least on smaller farms – most animals fed on grass rather than expensive grain, organic farmers can make savings at a time of high commodity prices. Adrian Dolby, of Barrington Park, said cutting input prices was one of his key reasons for putting 7,000 acres under organic cultivation in 2005.

"If we hadn't gone organic, we would have gone out of business," added Tom Rigby, who farms 160 acres near Warrington, most of it given over to pasture. "We are a small dairy farm and small dairy farmers are going bankrupt every day. I decided that if I was going to go bankrupt, I would rather do it in the way I wanted."

Rigby knows of larger producers that have quit organic methods, such as some bigger dairy farms that found their margins squeezed even on premium organic milk as they needed to import increasingly expensive feed. His smaller grass-fed herd avoids this problem, and his organically cultivated vegetables will be sold to Manchester University.

Oliver Dowding, an organic farmer near Wincanton in Somerset for more than 20 years, blamed waning interest among farmers on the numbers who entered organic cultivation several years ago, attracted by government grants to convert their land and the offers of subsidies, and who have since reverted to conventional farming as the financial support has dried up. This is a widespread view among organic farmers, and seems borne out by figures from Scotland which show a massive decline in the acreage under organic production since the early 2000s.

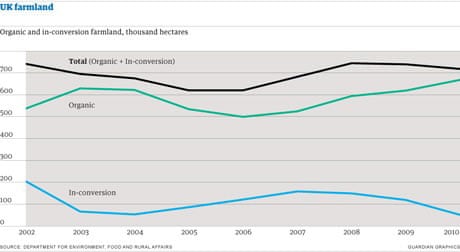

Last year, across the UK, only 51,000 hectares were in "conversion" – the process farmers need to go through to have their land and practices certified as organic. That is less than half the amount of land in conversion in 2009, itself down markedly from the 2007 peak of 158,000 hectares.

The rapid decline in "conversion" is not yet reflected in the amount of land in organic production overall in the UK, which has risen slightly. It takes several years to convert land from conventional production to organic production, in part because of the need to free the soil of fertilisers and pesticides.

That time lag, while land that has been in preparation moves into full organic production, created the small rise in the total area of land organically farmed last year – from 619,000 hectares across the UK in 2009 to 668,000 overall. As the decline in farmers entering organic conversion feeds through, the overall figure for organically farmed land is likely to stagnate or fall.

For livestock farmers, the picture is mixed. The number of cattle reared organically has risen steadily, to more than 350,000 last year. But despite widespread publicity by food campaigners on the claimed benefits of choosing free range or organic eggs and chickens, more than half a million fewer organic chickens, turkeys and other poultry were produced in the UK last year.

Amid falling sales overall, some specialists are thriving. Abel & Cole, the organic box scheme, expects a 40% increase in sales this year. Keith Abel attributes this to the same reason he believes organic sales have fallen overall – because the big supermarkets have taken organic products off the shelves to make room for cheaper non-organic goods. "It is a self-fulfilling prophecy: they take them off the shelves, and they sell less," he said. "But that's great news for me."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion