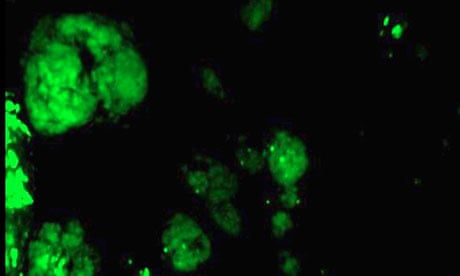

A group of women with ovarian tumours have become the first in the world to have surgery using a procedure that makes cancer light up in the body.

Operations were performed on 10 women as part of the first phase of a clinical trial to evaluate the technique, called fluorescence-guided surgery.

Doctors developed the procedure to help surgeons remove malignant tissue from ovarian cancer patients and reduce the risk of the disease returning months and years later.

The method illuminates cancer cells inside a patient's body to make it easier for surgeons to spot smaller cancers that can be easily missed, and to help them identify the borders between tumours and the healthy tissues that surround them.

Figures from 2008 show that 6,537 women were diagnosed with ovarian cancer and 4,373 died from the disease, according to Cancer Research UK. The disease is more likely to return if malignant cells remain in the body after surgery.

Many ovarian cancer patients have operations to remove or reduce the size of tumours before they receive other anti-cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy. But distinguishing tumours from healthy tissue can be difficult, with surgeons relying on a combination of feel and appearance to decide what material to remove.

With the new technique, surgeons could spot clusters of cancer cells as small as one tenth of a millimetre across, compared with around 3mm using visual and manual inspections. Doctors believe it will reduce relapses in the disease, caused by malignant tissue re-growing after patients have had surgery.

"Ovarian cancer is notoriously difficult to see, and this technique allowed surgeons to spot a tumour 30 times smaller than the smallest they could detect using standard techniques," said Philip Low at Purdue University in Indiana. "By dramatically improving the detection of the cancer, by literally lighting it up, cancer removal is dramatically improved."

Doctors performed operations on 10 women aged 41 to 76. Five had benign tumours, four had malignant cancer and one had a borderline tumour.

Before surgery, patients were injected with a liquid that contained a fluorescent dye attached to a chemical called folate. These build up in ovarian tumours because they contain more "folate receptors" than healthy tissue. During surgery, patients lay under a camera system that shone laser light on to the body. It detected which cells fluoresced and displayed them on a screen beside the patients.

"You see the image in real time as you work. You can zoom in and operate using the fluorescence," said Gooitzen van Dam, a cancer surgeon who led the study at Groningen University in the Netherlands. The operations are described in the journal Nature Medicine.

The surgeons found on average 34 tumours, compared with just seven picked up by traditional observations alone.

"This system is very easy to use and fits seamlessly into the way surgeons do open and laparoscopic surgery, which is the direction most surgeries are headed in the future," Van Dam said. "I foresee it becoming a new standard in cancer surgery in a very short time."

Much larger trials over longer periods are needed before doctors can be sure the procedure improves survival from ovarian cancer, but it is known already that follow-up treatments, including chemotherapy and radiotherapy, are more successful when less cancerous tissue is left in the body.

"What we are really after is a better outcome for patients, but if we had instead designed the clinical trial to evaluate the impact of fluorescence-guided surgery on life expectancy, we would have had to follow patients for years," Low said.

"By instead evaluating if we can identify and remove more malignant tissue with the aid of fluorescence imaging, we are able to quantify the impact of this novel approach within two hours after surgery. We hope this will allow the technology to be approved for general use in a much shorter time."

The team has ethical approval to trial the system on breast cancer patients and expects to perform several operations in the next two months. The method should reduce cases where too much breast tissue is removed, a problem that can lead to more mastectomies and more complex cosmetic surgery after cancer treatment.