Editor’s Note: Tune in all this week for a special series devoted to bullying and its damaging effects on children on “AC360º” at 8 p.m. ET. Then tune in Friday night at 8 ET for “Bullying: It Stops Here,” a special town hall discussion led by Anderson Cooper. Learn how you can take a stand at CNN.com/bullying and take the pledge on Facebook.

Story highlights

Jared Pettingill's parents wanted to make sure he wasn't bullied for being gay

They enrolled him in a public school that has taken steps to teach LGBT tolerance

A few miles away, another district is under scrutiny for its "neutrality" policy

That policy bars teachers from taking a position on homosexuality in the classroom

Jared Pettingill’s parents wanted a safe place for their son to attend school where he wouldn’t be harassed for being gay.

They found that place in the Minneapolis Public School district.

“It’s just been really accepting in my experience,” says Jared, a high school junior. He says he’s “never really dealt with bullying issues” in middle school or high school.

“The amount of positive reaction to LGBT issues is really amazing.”

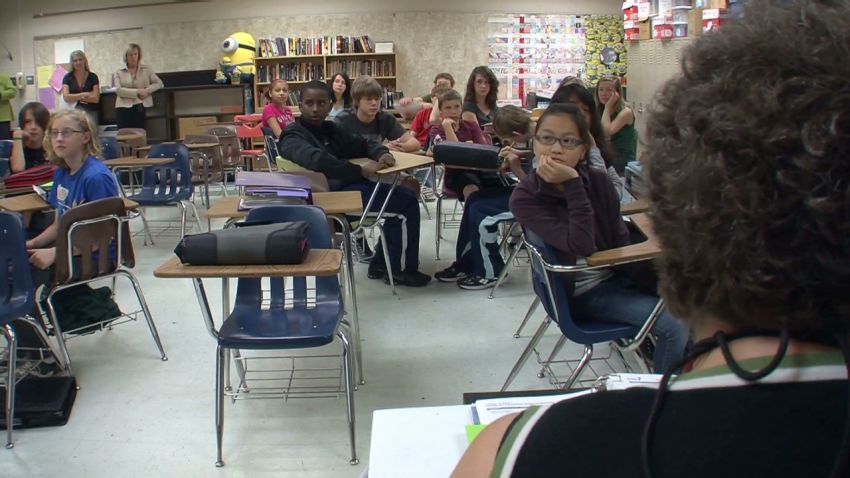

Minneapolis Public School administrators admit that by no means has bullying been eradicated from their schools. However, they firmly believe that they are leading the way in creating a safe environment for all students.

In January, the school board unanimously passed a unique resolution instructing administrators to track bullying incidents related to the harassment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students. The measure also requires all staff to be trained on LGBT issues. It injects LGBT topics into the curriculum, which includes adding an LGBT component to sex ed. They will eventually add an elective high school course on LGBT history.

Just a few miles away, another Minneapolis-area school district has attracted national attention for its policy that deals with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students much differently.

Neutral or not?

The Anoka-Hennepin School District, just outside the Twin Cities, made headlines in recent years after seven students committed suicide between November 2009 and May 2011. Parents and friends say four of those students were either gay, perceived to be gay or questioning their sexuality. They say, at least two of them were bullied because of their sexuality.

The school district says there is no evidence that the suicides were linked to bullying. Nevertheless, it stirred public debate over the school’s sexual orientation curriculum policy.

The district’s curriculum policy, adopted in 2009, bars teachers from taking a position on homosexuality in the classroom and says such matters are best addressed outside of school. It’s become known as the neutrality policy. Anoka-Hennepin, which encompasses the Twin Cities’ northwestern suburbs and is the state’s largest school district, is the only Minnesota school district known to have such a policy.

In July, gay rights advocates filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of a group of students challenging the neutrality policy. The Southern Poverty Law Center and the National Center for Lesbian Rights told CNN that the lawsuit is currently in mediation.

While the school district refrained from commenting on specifics in the lawsuit, it issued a statement in July noting that “Anoka-Hennepin has been recognized as a pro-active leader in the state of Minneosta on bullying prevention.”

The school district is also in the middle of a federal investigation into “allegations of harassment and discrimination in the Anoka-Hennepin School District based on sex, including peer-on-peer harassment based on not conforming to gender stereotypes,” according to a district memo.

Superintendent Dennis Carlson says the neutrality policy – which has attracted just as many local supporters as it has critics to heated school board meetings – is a reasonable response to a divided community.

“It’s a diverse community,” Carlson told CNN earlier this year, “and what we’re trying to do, what I’m trying to do as a superintendent, is walk down the middle of the road.”

The school district has a separate, comprehensive bullying prohibition policy, and Carlson said there is no link between the suicides and bullying.

“We have no evidence that bullying or harassment took place in any of those cases,” the superintendent said.

Carlson emphasized students need to report bullying, and he acknowledged “gay students in our district struggle with bullying and harassment on a daily basis.”

Damon Fietek, 16, knows that all too well. He says he was a target for bullies because his father, a middle school teacher in the Anoka-Hennepin school district, is gay.

Damon’s story

Jefferson Fietek had adopted Damon just before he started high school. The bullying began immediately.

“It upsets me a great deal,” says Fietek, a middle school theater teacher. “For him, being a kid from the foster system … I was just really upset that he wasn’t being allowed to celebrate the fact that he had a family now.”

Damon said the harassment went on for a full year before he even told his dad.

“Students would say stuff to me…like ‘Hey, did your dad rape you last night?’ You know, just make those kinds of jokes at me,” Damon said.

The bullying wasn’t just directed at him. He says it was a general hostility toward people who are – or are perceived to be – LGBT or who come from homes where a family member may be LGBT.

“I pulled him out of [that school],” Fietek said.

Damon now attends another school in the Anoka-Hennepin district with smaller class sizes. He says he hasn’t had any problems.

Fietek, an adviser to his school’s Gay Straight Alliance, says when he first started working at the school, several teachers suggested he keep his sexuality to himself for his own job security.

He decided it didn’t make sense to keep quiet. Risking his job is a gamble he says he has to take because the issue is too important.

“I just compare it to what these kids’ personal stories are, and they’ve got stories far worse than anything that’s happening to me,” Fietek said.

In his adviser role, Fietek says he receives phone calls, texts and Facebook messages several times a week from students who feel like they are at a dead end because of bullying or uncertainty regarding their sexuality.

Fietek believes the school district’s neutrality policy has indirectly taken the side of the bullies by not supporting these kids.

“Some of the things we’ve put in place [have] just created a scary environment,” Fietek said.

Making it better

James C. Burroughs II used to bully kids when he was in school, calling other boys “gay” for no particular reason.

“If you did something on the athletic field that wasn’t masculine or manly, you’d use the term ‘that’s gay’ or the ‘f’ word – the other ‘f’ word,” Burroughs recalled.

Today, Burroughs is the director of Minneapolis School District’s Office of Equity and Diversity, which seeks to “integrate equity, diversity, and inclusion into all aspects” of the school district.

Burroughs says his past is why he believes so passionately in putting an end to bullying, particularly of students who are perceived to be gay.

“What’s important for me is acknowledging that that happened and making it better for another generation of students,” Burroughs said.

The Minneapolis School District has taken many steps to address the issue of bullying LGBT students, including training its staff on tracking bullying of these students, injecting LGBT topics into the curriculum, hosting an “Out4Good” LGBT support program, and implementing a bullying prevention curriculum called Second Step.

“It’s very special,” Burroughs said. “I think we’re a national leader when it comes to making sure that students and families in the school system K-12 are being treated and valued equally amongst all students.”

Anti-bullying curriculum is woven into subjects like math, history and literature throughout each day, and staff from the teachers to the bus drivers are trained on how to create role play scenarios, says coordinator Julie Young-Burns.

Ultimately it comes down to how each teacher feels they’re best able to infuse the lessons into their already planned lessons on other topics, she says.

High school junior Jared Pettingill says he notices bits and pieces of an LGBT inclusive curriculum on a regular basis.

“In my English class right now, at the end of the year we’re gonna be reading a book called ‘Giovanni’s Room,’ which is all about a bisexual character living in Paris, and it hinges on a lot of his relationships,” he said. ” And there are a couple of other books like that that deal with lesbianism.”

His parents support the school’s proactive stance in teaching tolerance and offering support of LGBT students like their son. However, they say any policy is ultimately “a piece of paper” that won’t work unless the message is embraced by everyone.

“It is our public officials, it’s our media, it is each of us individually saying it’s not OK to be hurtful to somebody else,” said Marie Pettingill.

“Whether its LGBT or other issues kids experience, they should be able to be safe, and we shouldn’t have to even think that we have to talk about that. Kids should be safe.”

CNN’s Emily Probst, Poppy Harlow, and Chuck Hadad contributed to this report.

Watch Anderson Cooper 360° weeknights 8pm ET. For the latest from AC360° click here.