Story highlights

Bob Forrest was one of the worst junkies in Hollywood

He got sober for good in 1996, after 24 stints in rehab

He is Dr. Drew Pinsky's "head counselor" on "Celebrity Rehab"

A documentary on his life opens in theaters in January

One by one, the famous train wrecks and no-name junkies come to see the addict whisperer in his sunny aerie above the fabled corner of Hollywood and Vine. Eleven stories above the strip clubs and head shops and crowded sidewalks embedded with shiny golden stars, they seek Bob Forrest’s help in fighting their demons.

Forrest is a former rocker known for his intoxicated rants and onstage antics as the lead singer of the post-punk band Thelonious Monster. Yes, he fell off the stage and set the props on fire. That was part of the draw. Yes, he cursed out Jesus, said scary things about the first George Bush and mangled “The Star Spangled Banner.” That was over the top. And yes, he planned to kill himself on stage during a concert but chickened out. That was the monster talking.

He was one of the worst heroin junkies on the Hollywood club scene until he shocked everyone by getting sober in 1996. He says he delivered cocaine, crystal meth and heroin to some of the most famous people in the world. Helping addicts stay sober is his shot at redemption, or as Forrest puts it, “breaking even on some of the sh—y things I did in the past.”

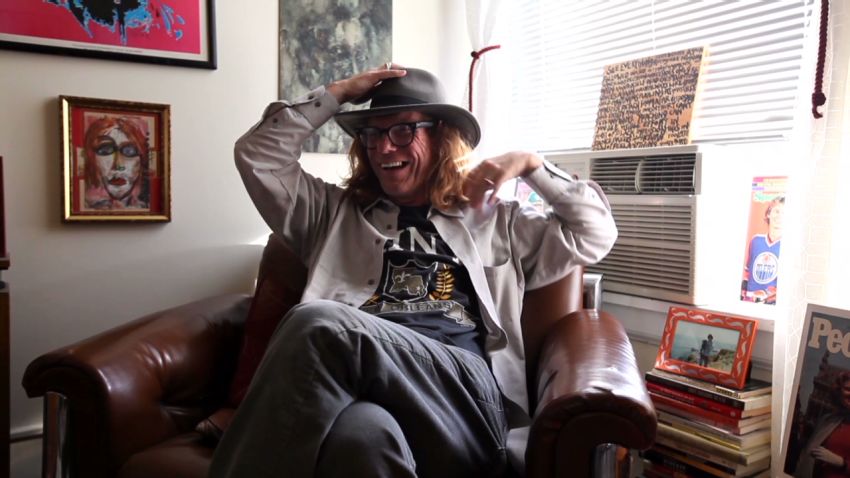

Heads turn when Forrest strolls down Hollywood Boulevard. Some people recognize him as Dr. Drew Pinsky’s trusty sidekick from VH-1’s “Celebrity Rehab.” He refers to himself as “the guy in the hat,” and it’s hard to miss that trademark fedora atop a shoulder-length reddish mop. His pale blue eyes peer out at the world from behind thick, black spectacles – the type musician Elvis Costello wore as an angry young man.

Forrest’s lined, pockmarked face is a road map of what a couple of decades of hard drinking and drugging can do to a person. He laughs when he tells the story about being mistaken for a panhandler when he showed up earlier this year for a guest appearance on Piers Morgan’s CNN show.

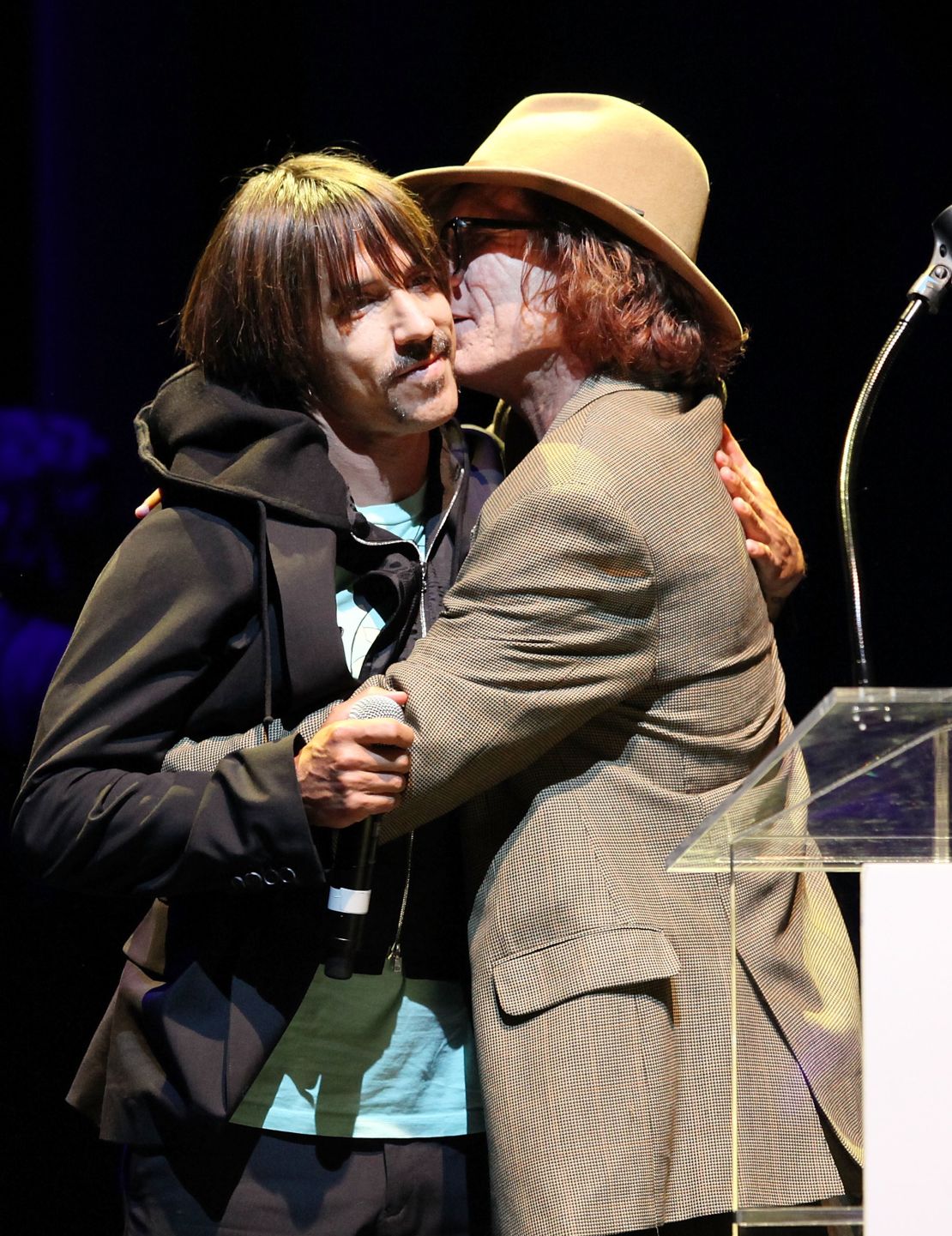

But Forrest knows his look resonates with clients, most of whom are 20-something and see him as “this cool old guy.” His footnote in music history – his band opened for The Red Hot Chili Peppers and Jane’s Addiction – and stories of rock ‘n’ roll excess give him street cred with the addicts he counsels in his office at Hollywood Recovery Services. He takes on about eight clients at a time – some famous, some wealthy, some with no money to pay him.

He’s undeniably charismatic and articulate and funny. And he has an uncanny way of getting through to even the most defiant addicts.

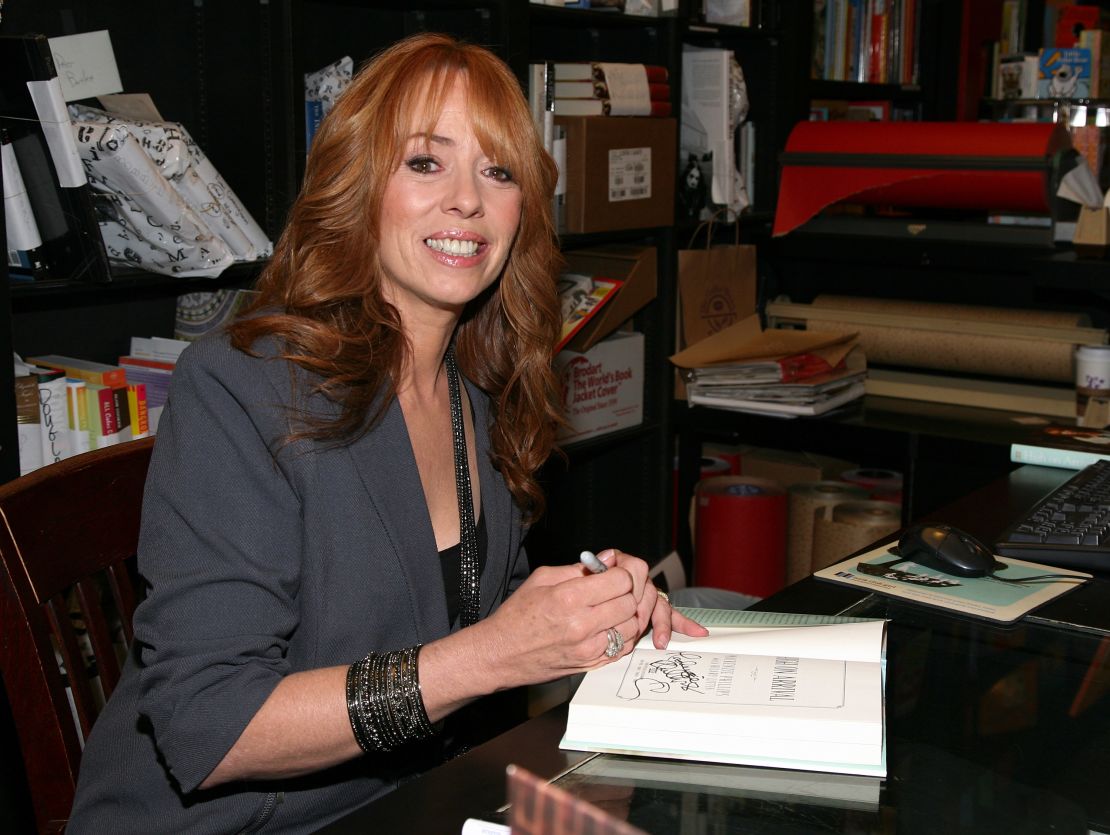

“Bob hasn’t forgotten what it’s like to be a junkie,” says actress and “Celebrity Rehab” alum Mackenzie Phillips. “He doesn’t talk down to you.”

Actor Eric Roberts (brother of Julia, father of Emma) is another “Celebrity Rehab” grad who kicked cocaine years ago and is on a mission to abstain from marijuana for 1,000 days. He calls Forrest “an instinctive genius.”

“Dr. Drew is a little clean-cut for my taste, but Bob is Mr. Funky,” he says, stopping by Forrest’s office one morning. “Don’t get me wrong, though. Bob will kick your ass.”

Now that he’s 50, and with 16 years of sobriety behind him, Forrest has found his niche in Hollywood. He’s a homegrown addict with a unique perspective on the deadly cocktail of addiction and fame.

As Forrest recounted his life story late last month, the sordid details of Michael Jackson’s overdose death were being detailed in court, starlet Lindsay Lohan and her father were in and out of jail again, and the final word came down on what killed singer Amy Winehouse: alcohol poisoning. It was just another week in the endless real-life drama of celebrity addiction.

What does Bob Forrest, addict whisperer and self-described straight shooter, have to say about fame and flameout? Plenty.

“I live in the belly of the beast. I have an office here in Los Angeles, and I have an office in Las Vegas. I don’t know how you could possibly see any more of this fame and ridiculousness.”

Experience has been his teacher.

The monster comes knocking

“My life is measured by album releases and the deaths of friends,” Forrest says. And the reign of the monster.

Recalling those times, this natural-born raconteur mixes up names, dates, and even the cities he was in. Is that the result of decades of drug abuse, or simply a function of being 50? Hard to say.

He tells a hilarious story about shooting cocaine in a motel with a famous rock star in Cleveland – or was it Chicago? – and hearing helicopters outside. Paranoid, they were sure the cops were coming with a SWAT team. Let’s pretend we’re asleep, they decided, crawling under the covers of the two queen beds.

What seemed like hours later, Forrest says he whispered, “Dude, we’ve got our clothes on. They’re gonna know we’re faking.” By then, the sun was up. They peered out the window and realized why they’d heard helicopters: The motel was next to the airport.

Forrest’s relationship with drugs may have its roots in childhood trauma, which he and PInsky see as the perfect petri dish for addiction. His life started out smoothly; he was a privileged kid – and a decent golfer – who was the center of attention at home in Palm Springs, California.

Sure, his parents drank, but didn’t everyone’s? One day, while they were drinking, a secret slipped out, and the bottom dropped out of Forrest’s world. His sister, he learned, was actually his mother. “Sister mom,” he calls her. And the people he thought were his parents were his grandparents.

Forrest was 13, and he remembers feeling angry that his family had lied, but he didn’t ask questions. He holed up in his room, reading. A passage from Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road” became his credo:

“The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing but burn, burn, burn, like fabulous yellow Roman candles …”

He longed to be like Kerouac and was so deeply affected by a biography of comedian Lenny Bruce that he thought shooting heroin might be cool. He’d do just that for the first time at 21, with a blues musician named Top Jimmy.

But first there were the rum and Cokes. The alcohol helped soothe the pain of a sudden fall from the upper-middle class when the man Forrest knew as his father died and, at 15, he moved with his family to a trailer park.

“I knew I was an alcoholic at an early age because I drank with people in high school who really didn’t want their parents to know and didn’t want to go home and were worried,” Forrest says. “I wasn’t worried. I wanted to drink until the sun came up. And then I found other people who wanted to drink until the sun came up.”

After high school, he attended Los Angeles City College and discovered the clubs and the emerging punk-grunge scene. He dropped out and was working as a DJ when he befriended a couple of guys named Flea and Anthony. They also liked to party until the sun came up, and he let them sleep on the floor of his apartment.

The L.A. club scene in the 1980s was burbling with talent and creative energy. Courtney Love was there and maintains a friendship with Forrest to this day. Jane’s Addiction was on the rise. Forrest’s friends – Flea, whose given name is Michael Peter Balzary, and Anthony Kiedis – formed the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Forrest fronted Thelonious Monster. Another hard-partying friend, John Frusciante, was about to sign with Forrest’s band but joined the Chili Peppers instead.

The 1988 overdose death of the Chili Peppers’ guitarist, Hillel Slovak, was enough to convince Kiedis to enter rehab, but Forrest wasn’t ready. His band was getting some buzz, and he didn’t want the party to end.

That year, he was invited to talk about a new album on an L.A.-based radio show, “Loveline,” but he showed up wasted. The show’s host, Dr. Drew Pinsky (who would go on to create a prime time show on HLN, CNN’s sister network) wrote him off as someone not long for this Earth.

“He was a horrific drug addict,” Pinsky recalls. “I told him if he took care of himself he could do great things. I declared to everybody, ‘This guy is dying.’ There was no way he could survive that kind of addiction.”

But he did, and if anything, it only got worse. By 1993, Thelonious Monster was on the verge of breaking up. Other bands were passing them by, and it ticked Forrest off. He didn’t stop to think the reason might be that he, the band’s front man, was a full-fledged heroin addict.

“I was crashing down,” he recalls, “I spent so much money on drugs and lawyers and trying to get out of trouble that I didn’t even have a place to live, even though I had albums out and was playing concerts. I had gotten to a place where I was spending $300 to $500 a day on drugs.”

When the tour ended, all he had waiting for him was a crack motel. “So I just decided to go out with a bang.”

He’d kill himself onstage at the annual Pinkpop Festival in the Netherlands and make the front pages of newspapers around the world.

“I had planned to climb to the top” of one of the speaker towers “and jump off,” he says. “That is how far gone I was – mentally ill, drug addicted, hopeless and caught up in this whole stupid idea of what people say about me is so important, but what I internally have is just nothingness and darkness.”

In the end, he couldn’t do it. “I got up there and got scared. I became paralyzed.”

What happened next can be seen on YouTube and is painful to watch. Back on stage, he runs in circles and tries to wrap one of his bandmates in duct tape. He gets tangled in the microphone wire, slips and falls. Someone untangles him but he just lies there, and then slowly begins to curse out Jesus.

Finally, he finds his way to a speaker, where he sits slumped over as he finishes the song.

The crowd eats it up.

Fame and flameout

Addiction’s “friend” can take many forms: companions, lovers, family, managers, assistants, fans, wannabes – even doctors.

After his flirtation with death at Pinkpop, Forrest saw the powerful role the audience can play. The publicity boost his aborted suicide gave Thelonious Monster kept the band going for several more months, he says. His bad behavior was being rewarded.

“People are watching you self-destruct and then you in turn feel like you need to reciprocate with them by self-destructing.”

It’s a celebration of the negative – and a constant dance in Hollywood, if headlines are any indication. In the end, only the addict can control how the journey ends. But along the way, there is no shortage of enablers.

“Michael Jackson was enabled to death,” says Tatum O’Neal, a longtime friend of Jackson’s who has fought addiction. “Everyone around Michael Jackson, shame on all of them,” she scolds. “What no one is saying is Michael Jackson was an addict. He had no veins left. His behavior was drug-seeking.”

Anyone who says so faces a Twitter fury. “They’re like bullies,” O’Neal says, adding that she received a barrage of hateful tweets after suggesting on Piers Morgan’s show that Jackson had a problem with controlled substances. Mackenzie Phillips also received hate tweets after speaking out about Jackson’s drug issues.

But the sad truth was borne out by testimony at the manslaughter trial of his personal doctor and underscored by Jackson’s own slurred voice, captured on Conrad Murray’s iPhone.

Families of celebrity addicts become the worst enablers when they have a financial stake and can’t say no, Forrest says. They fear being cut off, emotionally and financially.

“If you’re generating revenue, then nobody questions you,” Forrest says. “And so, Michael Jackson being the greatest revenue generator in music history, no one questions him. Not his family, who are living off him. Not his managers, because he can always get another manager.

“I feel for the family of Michael Jackson, who have to come to grips with woulda, shoulda, coulda. They’re at this dilemma constantly: ‘What do we do? We can’t stop him.’ And you can’t. With people that powerful and that wealthy, the only thing that gets them sober is the fear of death.”

Murray’s trial focused the national conversation on the role of unscrupulous doctors and prescription drugs in the ever-evolving world of addiction. District Attorney Steve Cooley said Murray’s conviction serves as a warning to every “Dr. Feelgood.”

It’s about time, Forrest says.

“When Heath Ledger died, I thought people would be all over the prescription drug tsunami that is killing young people all over America,” he says. “But instead, within 72 hours it was all about how Heath Ledger couldn’t (move on) from ‘Batman.’ Where did that narrative come from? He couldn’t stop being Joker? Really? That’s why he choked on his own vomit? I hate to be so rude, but honesty is the only way we’re going to get some sanity about this enabling.”

Narcissism, unlimited cash, childhood trauma, chaotic families and star-struck hangers-on are all it takes to feed an addiction, he says, and Hollywood has those ingredients in spades. If you are famous, your doctor is impressed and even your drug dealer feels important, he adds.

Pinsky studied the link between narcissism, celebrity and addiction, and published his findings in a book, “The Mirror Effect.” He says narcissism is grounded in childhood trauma that leaves a person feeling empty and incomplete. Narcissists gravitate toward fame as a way to fill the void, and addiction is another way to relieve the feeling of emptiness, he says. Celebrities are insulated and famous addicts can avoid consequences until the problem is severe.

As celebrity addicts spiral, the people around them get sleazier. “I watched that with Tom Sizemore,” Forrest says. The acclaimed actor got addicted and went to jail after assaulting his girlfriend and fellow addict, Hollywood madam Heidi Fleiss. “He’s over two years sober now, but he just kept getting sleazier and sleazier managers and taking lamer and lamer roles,” Forrest says. “You’re building a career from ‘Natural Born Killers’ and ‘Saving Private Ryan’ to this slow downward spiral. Guys who don’t even have offices are your manager; they manage with cell phones in their cars.”

Celebrity addicts acquire “too much posse,” he says, surrounding themselves with sycophants and parasites who pose as friends. Mackenzie Phillips, who relapsed after a decade of sobriety, says she moved some “old friends” – translation: drug dealers – into her house to keep her cocaine supply flowing.

“When you’re going down like that and you’re crazy, only the weirdos of Los Angeles latch on to you, because you’re providing a free place to live and free drugs and free sex and cable TV,” Forrest says. “The people hanging out with you are opportunistic, gutter-dwelling people. I was that, so I can judge. I was that to a lot of people in this town.”

‘Why does this keep happening?’

“Want to see where I died? It’s right around here,” Forrest says, suddenly steering his Prius off Melrose Avenue and onto LaBrea. He pulls a U-turn and glides up behind a bus in front of Pink’s iconic hot dog stand, which has stood at the corner for more than 70 years; its famous chili dog is a favorite celebrity snack to top off a night of club hopping or awards show photo ops.

He idles the Prius and tells the story: It was some time in 1993 or early 1994 and he’d just gotten out of jail, scored some heroin and used the last of his money on a cab. When he overdosed in the back, the driver dumped him on the street, sometime before the sun came up. Forrest got lucky. He was near the bus stop popular with employees at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. A nurse gave him CPR and called 911.

He refused to go back to rehab because he saw his overdose as “a simple mistake.” It would take a couple of more years, several more jailhouse detoxes and several more overdoses.

“Being high is extraordinary,” Forrest says, “beyond the place of worry, like being safe and warm. Detox is a hell unlike any other, like a terrible flu combined with panic and fear and hate.”

During detox, addicts don’t sleep and can’t eat. They have stomach cramps and throw up.

“You’re exhausted, suicidal, crying, feeling great sadness and grief, all rolled into one big nothingness,” Forrest adds. “You feel everything. One addict told me, ‘My eyelashes hurt.’

“I formally detoxed 24 times in rehab. But probably 50 times I have gone through that,” he says. He finally got clean in 1996 after waking up in the rain, “soaking wet, toothless and down to 120 pounds.” He asked himself, “Why does this keep happening?” And then it dawned on him: It’s the drugs.

Ten years after he wrote Forrest off as hopeless, Pinsky was surprised to run into him again at a seminar on chemical dependency. Forrest was a star AA sponsor by then, and was spending most of his time volunteering at the Musicians Assistance Program, helping the music industry’s endless supply of addicts.

“He’d added the hat and the glasses, and I thought, ‘That guy looks like Bob Forrest but there’s no way Bob Forrest is alive,’” Pinsky recalls. “But it was Bob and he was working in recovery. And he was good.”

Pinsky offered Forrest a job at Las Encinas Hospital, where he was working in addiction medicine. Forrest says he took the job because he was running out of money and thought he might as well get paid for what he was already doing free. The deal struck, Pinsky advised Forrest to clean up his rock ‘n’ roll way of speaking, especially his penchant for dropping f-bombs.

“Get a dictionary,” he said. “You work in a hospital now.”

Life after heroin

Life is good when the monster is sleeping.

These days, Forrest is enjoying being present in his life. He has a year-old son named Elvis, and Forrest and his much-younger girlfriend, Sam, are fixing up a house in Encino, the suburban heart of the glitz-free San Fernando Valley.

He loves Hollywood and musicians and drug addicts, and he’s cool in the manner of underground hipsters. That is unlikely to change, even if he moves to the suburbs. He’s just not a Dockers kind of guy.

“I don’t think you get sober to shop at Wal-Mart and become like everybody else,” he says.

He buys records and devours music magazines, even if he doesn’t play in the clubs anymore. He used to fear performing would make him want to get high; now he just thinks aging rockers are “pathetic.”

Most weekends, he can be found on the film-festival circuit promoting “Bob and the Monster,” a documentary about his life that is due in theaters in January. Later this month, he can be seen back at the Pasadena Recovery Center when VH-1 airs more installments of “Celebrity Rehab Revisited.” Forrest has a book deal in the works. And there’s the weekly radio show, “All up in the Interweb,” on indie1031.com.

Once again, Bob Forrest is almost famous.

The radio show is a labor of love; there’s no paycheck and one of his producers, “Nate the Man” Pottker, holds down a day job as Bob Forrest’s favorite Starbucks barista.

“All Up in the Interweb” is laced with Forrest’s social commentary, and much of it centers on addiction and recovery. He believes the “anonymous” part of Alcoholics Anonymous is outdated, especially in Hollywood. Rather than protecting an addict’s identity, he says, it now implies a stigma. And asking an addict if he or she is willing to give up everything for a cure rings hollow to affluent celebrities, he says, who “are accomplished artists and musicians and have houses all over the world.”

He opened Hollywood Recovery Services after growing dissatisfied with what he calls “the for-profit recovery industry” and its “cookie-cutter” emphasis on placing “heads on beds.” He prefers the old-fashioned, one-on-one approach of talk therapy, and he believes it takes a year or more to fully regain sobriety – not just the 28 days in “the rehab bubble” that is covered by insurance.

Society needs to stop looking at addiction as a moral issue, Forrest says. “When friends get cancer, everybody goes on the Internet and tries to find out everything about cancer. But when they have addiction, it’s just like, ‘Oh, whatever, they need to grow up.’”

The point was embraced recently by the American Society of Addiction Medicine, which updated its definition of “addiction.” It is now considered a chronic brain disorder, not simply a behavioral problem.

“Let’s get the stigma out of this,” Tatum O’Neal agrees. “We’re not bad people. We’re not immoral people. We’re not weak people. We’re sick people, and we need help. We don’t deserve the scarlet letter.”

Prescription pain medications kill 15,000 people in the United States each year, more than heroin and cocaine overdoses combined, according to a report this month by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. At the center of that epidemic is Bob Forrest.

On the walls of the waiting room at Hollywood Recovery Services, he has hung two black and white photos of punk rockers. One is of Darby Crash, a heroin addict who died of an overdose. The other features Ian MacKaye, who started the “straight edge” punk movement, whose adherents avoid drugs, alcohol, promiscuous sex – even meat.

Forrest could have gone either way, but ultimately found a third path. He didn’t burn out, but he didn’t fade away, either.

“I think it’s extraordinary that he recovered and continued his passion for life and wanting to make changes,” says Keirda Bahruth, the documentary director. “That’s what the Kerouac passage was all about. He still has his youthful rebellion and hope and energy.”

He remains “mad for living,” as Kerouac so famously described it. “The problem is,” Forrest says, “people have to stay mad for living the whole time.” And so, he blends early inspiration with his own hard lessons in the lyrics of “Burn, Burn, Burn,” a song he wrote for the documentary:

“Don’t have a religion, but I do have faith

Love is the answer to the burnin’ ache

‘N friends have come, you know, ‘n friends have gone

To throw your life away’s so f—in’ wrong

The trick is to burn, burn, burn but don’t burn out.”

As Bob Forrest likes to say, “It’s worth sticking around just to see what happens.”