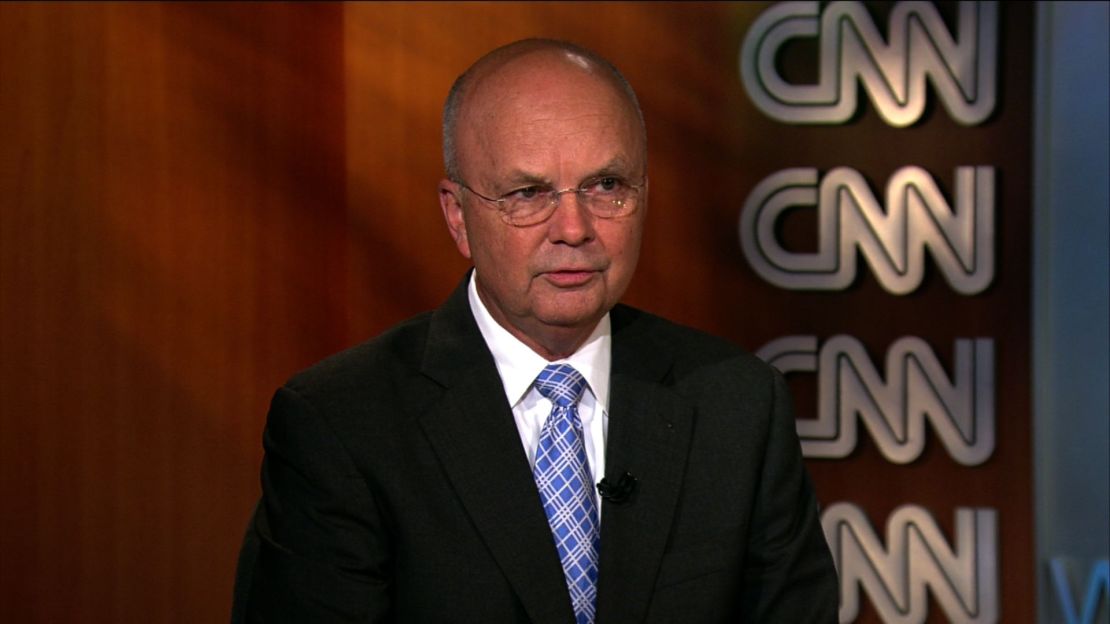

Editor’s Note: Gen. Michael V. Hayden, who was appointed by President George W. Bush as CIA director in 2006 and served until February 2009, is a principal with the Chertoff Group, a security consulting firm, and a distinguished visiting professor at George Mason University. He formerly was director of the National Security Agency and held senior staff positions at the Pentagon.

Story highlights

Last week saw death of Gadhafi, plan to withdraw all U.S. troops from Iraq

Michael Hayden: U.S. is ramping up its responsibility in one Arab country, leaving another

He says it's vital to make sure Libya doesn't turn into a "Somalia on the Mediterranean"

Hayden: Rulers in Syria, Yemen, Iran will draw lessons from fate of Gadhafi

U.S. security policy showed the effects of two substantial pivots this past week: ramping down our role in regime transformation in one Arab country even while ramping up our responsibility in another.

First to Libya, where the death of Moammar Gadhafi has finally ended the first act of what promises to be a long drama. As Iraq and Afghanistan have amply proven, collapsing the old regime is the easy part; building a functioning civil society is the real challenge.

Gadhafi’s apparent execution after he was captured, on top of the still unexplained murder of the anti-Gadhafi forces’ commander Abdel Fattah Younis three months ago, highlights the chaos and infighting that still exist in Libya and the need to help the Libyans build a viable state.

Michael Scharf: Investigate Gadhafi’s killing as a war crime

There is more than altruistic international good citizenship involved here. If Libya is left to its own devices, it is not difficult to conceive of it becoming Somalia on the Mediterranean, an ungoverned space threatening the heart of Europe as well as critical international lines of communication. We have already begun to fret over the loss of control of thousands of man-portable surface-to-air missiles. These are reasons enough to stay engaged.

There are other effects from this week’s success that will also need to be managed. NATO stretched the United Nations’ mandate to “protect civilians” as far as legally possible (about as far as we domestically stretched the definition of “not war”), actively isolated portions of the battlefield to ensure local advantage to the anti-Gadhafi fighters, and conducted what at times looked like close air support – integrating NATO airpower with the fire and movement of their ground forces. What impact will being the air force for the National Transitional Council’s fighters have on Security Council members when next they face a question of “protecting” civilian populations?

Are reprisals an inevitable byproduct of revolution?

The Libyan success will also have to be managed within NATO. It was American intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, defense suppression, electronic warfare, refueling and precision weapons that kept the alliance in the game. Will the lesson be that Europeans will have to do more in the future? Or did the Libyan adventure teach them that current levels of investment are “good enough”? It’s not an idle question, as many seem to already be crowding around the exits in Afghanistan.

And this week’s events in Libya will have regional impacts. For Egypt and Tunisia, they hold the long-term prospect of a like-minded neighbor. For rulers in Syria and Yemen, they pose an existential question: Does Libya teach me what happens if I stay too long? Or does it simply reinforce what I already knew – that the stakes of this game are very high and I have to do whatever I have to do to win? For rulers in Tehran the issue is less ambiguous: So this is what the West might do to you if you give up your nuclear program.

Gadhafi and son buried in undisclosed location

While managing these byproducts of success in Libya, the president also announced that, by the end of the year, “the last American soldier will cross the border out of Iraq with their head held high, proud of their success.”

For some in the United States and in Iraq this was a rewarding moment, the end of a bad chapter for both peoples. Others, though, smell danger. Many had expected a sustained American presence; even Iraqi military leaders had talked about the continuing need for training, intelligence, logistics and air defense from the United States.

There was also just the raw political impact of a continued American footprint. In the north, Americans on the ground had dampened native passions along an Arab-Kurd-Turkmen fault line. American presence overall gave heart to those in the Iraqi political spectrum who would oppose undue Iranian influence in Iraqi affairs. That presence also seemed to help manage Turkish reaction (and potential overreaction) to PKK raids allegedly mounted from Iraq. And for Iraqi Sunnis, a visible American footprint was often seen as their best guarantee against the actions of what many viewed as a predatory Shiite government.

In short, a continued American presence was seen as calming, buying time for Iraqi politics and institutions to grow to meet the demands they are facing.

To be sure, the United States is not abandoning Iraq. Our talented ambassador there, Jim Jeffrey, will have some 16,000 government employees and contractors under his command. But this is not the same as an enduring military presence.

Many seemed to realize this. American commanders in Iraq regularly called for a substantial five-figure residual force, and two successive secretaries of defense advocated publicly for a continued American presence, even as the president they served did not draw back from his campaign commitment to end the American military’s role there.

In the end, though, it was the Iraqis, and especially Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, who could not deliver on the one nonnegotiable American demand – immunity from Iraqi law for U.S. troops. No American administration could accept anything less.

Given al-Maliki’s worldview and his fragile political situation, it was hard enough to wrest this concession from him in 2008. It required a sustained, unrelenting, personal effort from the highest levels of the U.S. government, and success was never guaranteed. It is not clear that similar efforts were made in 2011.

Obama makes war policy an election strength

In any event, the president chalked up the U.S. withdrawal as a “promise kept,” even as his officials worked to the last minute to sustain a U.S. presence.

In both Iraq and Libya it was an interesting week: engagement and disengagement, leadership and resignation, moving in and moving out – with both the burden and the necessity of global leadership on clear display.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Michael V. Hayden.