Chris Sangster tilts his head upwards so the light on his helmet picks out a pale vein of quartz on the roof of the narrow mine. "Think of that running 100 metres above you and 200 metres below. That's where you'll find the gold." Behind him on an old rail line, lies a rusting trolley. Water drips from the roof, pooling between the tracks.

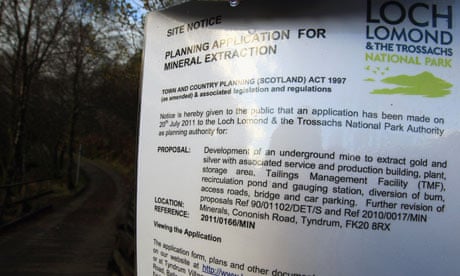

The mine, tucked into the hills of Glen Cononish, near Tyndrum, some 50 miles (80km) north of Glasgow, has been derelict since the 1980s when it was first sunk but not developed after a collapse in gold prices. But after permission was granted this week by the Loch Lomond and The Trossachs national park authority, what would be Britain's only commercial goldmine could be operational as early as spring of next year.

It is the second time Australian-backed mining company Scotgold has applied to mine gold and silver at the Cononish site, which it bought in 2007. It was turned down last year over concerns about size and restoration, but after making amendments to the original plan, the park authority granted permission.

At current prices, Scotgold believes there could be around £170m of the precious metals in the site, which could be extracted over the 10-year project. At least 50 jobs will be created and money will go to the local community to help develop a visitor and heritage centre.

"We can now move things forward," said Sangster, a veteran mining engineer and Scotgold's chief executive. "We are looking at financing options for the project and if it all goes well, sometime in April or May it will kick off."

Down in the village of Tyndrum, a popular tourist and walking centre bisected by the West Highland Way, locals talk positively of the project in the hills above them. The area has long attracted amateur gold-panners, and John Riley, of Strathfillan community council, says the community is excited about the development.

"The mine will provide obvious advantages in employment, training and education for the young people and others in the community, which will have all sorts of knock-on effects on ancillary trades and the hotels and guest houses," he said. "People will want to come and see the mine. It will have a very beneficial effect. Obviously there are environmental issues but we think they have been very adequately addressed."

Opponents, however, say the project's approval makes a mockery of the founding principles of the country's national parks, where conservation of the environment should be the overriding concern.

"If it were artisanal, a small scale mining operation, even if it went the way of a museum-type facility, that would be a better prospect for a national park than the full-scale industrialisation of a Highland glen," said Bill McDermott, of the Scottish Campaign for National Parks. "We are talking about millions of tonnes of spoil being deposited in the glen. They will shape it, of course, but it will never be the same as it was before."

Hebe Carus, access and conservation officer at the Mountaineering Council for Scotland, is also concerned about the visual impact of the mine. "It is going to be a pretty alien looking feature in a relatively wild area. Just the fact that it is in the heart of the wild area, surrounded by all these mountains where people walk to get away from it all."

It takes one tonne of rock to produce enough gold particles to fashion a wedding ring. Chris Sangster says over the course of the project, some 400,000 tonnes of spoil will be produced then landscaped into the glen. The visual impact when finished will be minimal, he says. The gold, meanwhile, will be extracted using gravity and flotation processes, without resorting to older methods involving cyanide or mercury.

"We accept there are short to medium-term impacts, but in the long-term these impacts will be successfully mitigated," he said.

Linda McKay, convener of the national park authority, says the authority has thought long and hard about the proposal but felt the project allowed for a balance between conservation and the needs of the local community.

"It left us able to find a way to recognise the sustainable needs of the community with the very, very significant role that we have as a park to protect and enhance the environment," she said.

There are fears, however, that the project could set a precedent for development elsewhere in the Loch Lomond park, or in other national parks.

"The national parks have been designated primarily because of their landscape," said Carus. "If this becomes a trend I don't think the national parks will be delivering what they were set up to deliver."

Gordon Watson, head of planning for the park, believes such fears are unfounded. "This is pretty unique. It does not open the door to other quarries happening. We have treated this as very specific."

Back in Sangster's office, housed in Tyndrum's tiny railway station, a large map is marked out in vivid coloured patches, stretching well beyond the Loch Lomond park area. Scotgold has a crown licence to look for gold in a 3,000km square area that stretches from Upper Knapdale in Argyll to Pitlochry in Highland Perthshire.

"The other part of our business is exploration," said Sangster. "We are actively looking within a relatively short distance of here."

In Glen Orchy, about six miles from Tyndrum, some test holes have been sunk. The prospects, says Sangster, look good.