Story highlights

"Stress in America" report emphasizes toll of caring for chronically ill relatives

55% of caregivers reported feeling overwhelmed, American Psychological Association says

In survey of 1,226 Americans, 39% said stress levels had increased in past year

"People who care for loved ones ... don't take care of themselves," psychologist says

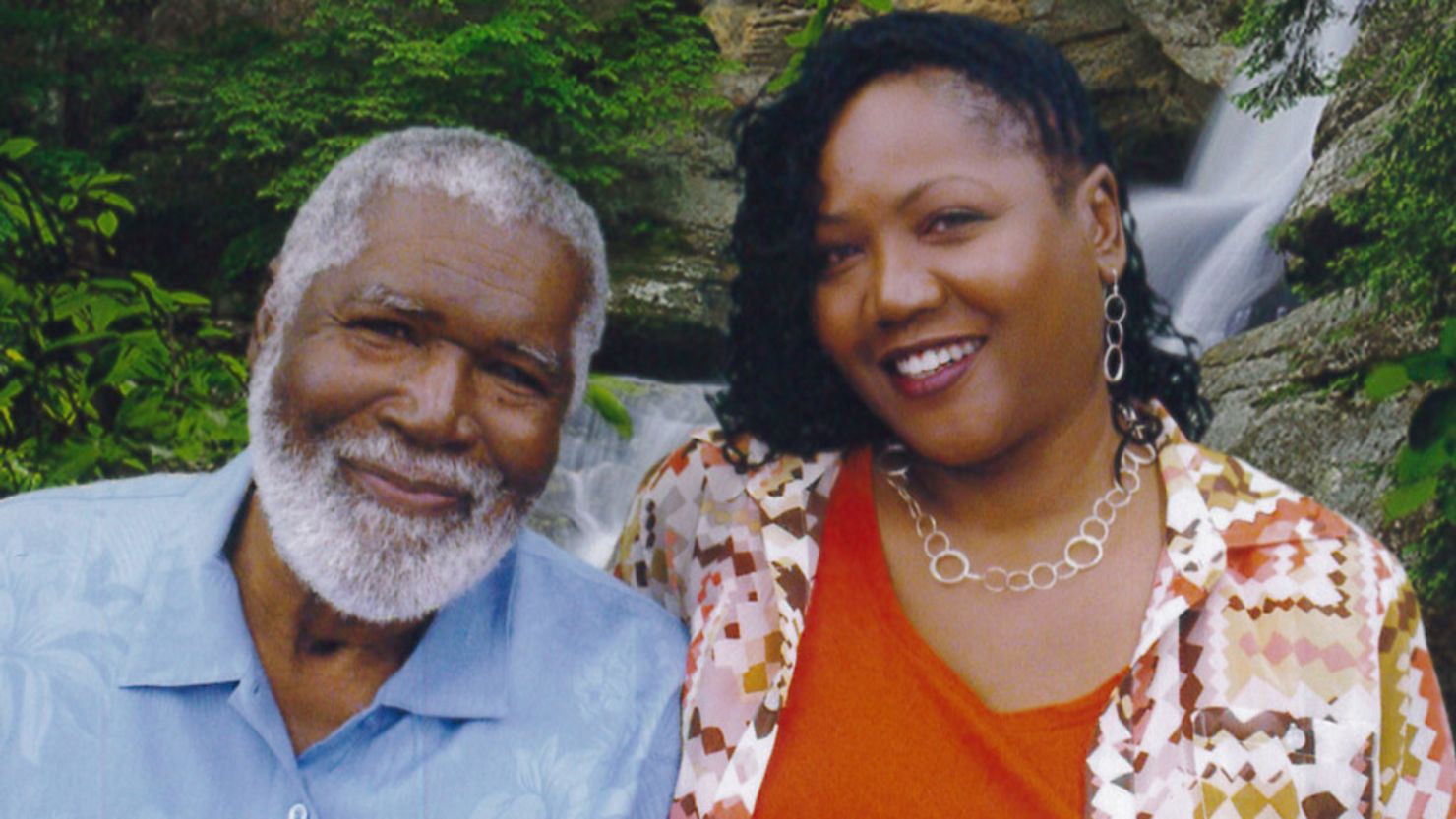

Whenever Felicia Hudson gets overwhelmed juggling a full-time job and caring for her ailing father, she finds solace in a piece of paper hanging in her office.

“Circumstances do not cause anger, nervousness, worry or depression … it is how we handle situations that allow these adverse moods,” it says. “We actually choose our own attitudes. I choose to be calm, well-adjusted and happy!”

She can’t remember where she found the motto, but focusing on it is one of several coping mechanisms Hudson has developed since she took her father out of a nursing home in July 2008 and moved him into her two-bedroom apartment in San Diego.

By then, 72-year-old Alvin Hudson had suffered three strokes and been diagnosed with diabetes, kidney failure and renal disease, requiring a long list of medication and dialysis three times a week.

It was only a matter of days before Hudson became overwhelmed, she says.

“It was like, ‘oh my, what did I get myself into?’” the 51-year-old Georgia native recalls. “Sometimes, I would just go into the bathroom and cry.”

She laughs about it now, but in the beginning, “it was horrible,” she says.

She’d go to her job at a manufacturing plant at 8 a.m., leaving at lunch three times a week to bring her father to a dialysis center. She’d return to work and stay late to make up the time, and then go back to the center to pick him up. Those were just the normal days. If he had an extra appointment with the dentist, podiatrist or general practitioner, she took the day off to shuttle him around and sit in waiting rooms.

“I put my life on hold,” she said. “I was trying to do it all.”

It’s a scenario familiar to many across the United States as adult children become caregivers for aging and chronically ill loved ones. With the first of the baby boomers turning 65 in 2011, the number of Americans entering retirement age is expected to nearly double by 2030, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration on Aging.

As the country braces for the prospect of providing health care to roughly 72 million adults, the impact on caregivers is coming into focus. A study released last week found that Americans caring for aging and chronically ill relatives reported higher levels of stress, poorer health and a greater tendency to engage in unhealthy behaviors to alleviate stress than the population at large.

Moreover, 55% of caregivers reported feeling overwhelmed by the task at hand, according to the American Psychological Association’s “Stress in America” survey, which was conducted online among 1,226 adults in the United States in August and September.

While emphasizing results among caregivers, the survey also found that 22% of Americans reported “extreme stress” and 39% said their stress had increased over the past year. Those results were higher among caregivers, who were also more likely than the general population to report doing a poor job at managing and preventing stress, according to the survey’s findings.

“People who care for loved ones tend to take on a lot, but don’t take care of themselves,” said Beverly Hills psychologist Fran Walfish, who helps look after her 90-year-old father. “It’s easy to neglect yourself when you try to be all things to everyone else, but something has to give and it catches up with you.”

The report emphasizes the public health implications of high stress levels, with caregivers reporting greater rates of high cholesterol, high blood pressure, obesity and depression.

“It takes an incredible amount of self-awareness but you have to be willing to say I need help, I’m not omnipotent,” Walfish said. “It’s impossible to be all things to everyone, so what we have to do is have honest straight talk with ourselves about how much we can handle and when we seek help from others.”

The same lesson applies to those who are stressed, without the added burden of being a caregiver, she said. Significant sources of stress among respondents included money (75%), work (70%), the economy (67%) and relationships (58%), according to survey results.

Regardless of the cause, stress often results from taking on too much and not knowing when to stop or ask for help.

“People feel a lot of pressure, especially in this economy, to not complain or set limits for themselves. Before you know it, you can have a bodily reaction that can be very negative, from extreme depression to heart attack or stroke,” said Andrew Spanswick, chairman and CEO of KLEAN, a residential addiction treatment center in West Hollywood, California.

“Americans are chronically sleep-deprived and overworked, so most people could really benefit from taking time for themselves and figuring out a way to relax,” he said.

For low-income households, a reprieve can be hard to come by. Even as work piled up around her, Hudson didn’t complain, fearing for her job security. She’d lie awake at night worrying about finances. With the rest of her family across the country in Atlanta, she felt alone. She lost contact with friends, put on weight and began to neglect basic household chores amid the hustle of work and caring for her father.

Help finally arrived for Hudson and her father when they discovered an all-inclusive elder care center that accepted Medicaid. St. Paul’s PACE, which stands for Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly, functions like a day care for the elderly, providing medical services, social outlets and meals under one roof, along with transportation to and from the Bankers Hill campus.

“What we usually encounter is a very overwhelmed adult child who is trying to work and can’t keep things together. Oftentimes, their house is a mess, they’re financially burdened and they no longer have outside ties to the community because all their time is spent caring for the mom and dad,” said Amanda Gois, marketing director of St. Paul’s PACE.

“The adult child is almost at the point of resenting the parent they love and the parent is often depressed and withdrawn and has lost a desire to thrive or connect with the community because he or she doesn’t want to be more of a burden,” she said.

Now, Hudson no longer has to bring her father to appointments. The program picks him up from home three times a week and brings him to the center, where he receives his medication and has lunch with other clients. The program also brings him to the dialysis center and back before returning him home. One night a week, someone from PACE comes to the home and cleans his room, changes his sheets and provides extras like a foot rub.

“The goal is she can now enjoy her dad versus having to care for her dad,” said Gois.

For Hudson, it’s working. She joined a gym with a goal of taking off her caregiver weight. She has the ability to focus on her job and work overtime if she wants.

At home, she still occasionally takes refuge in the bathroom if she has a disagreement with her dad. But it’s a world of a difference from when they first became roommates, almost four years ago.

“It’s a godsend,” she said. “I’m finally getting my life back.”