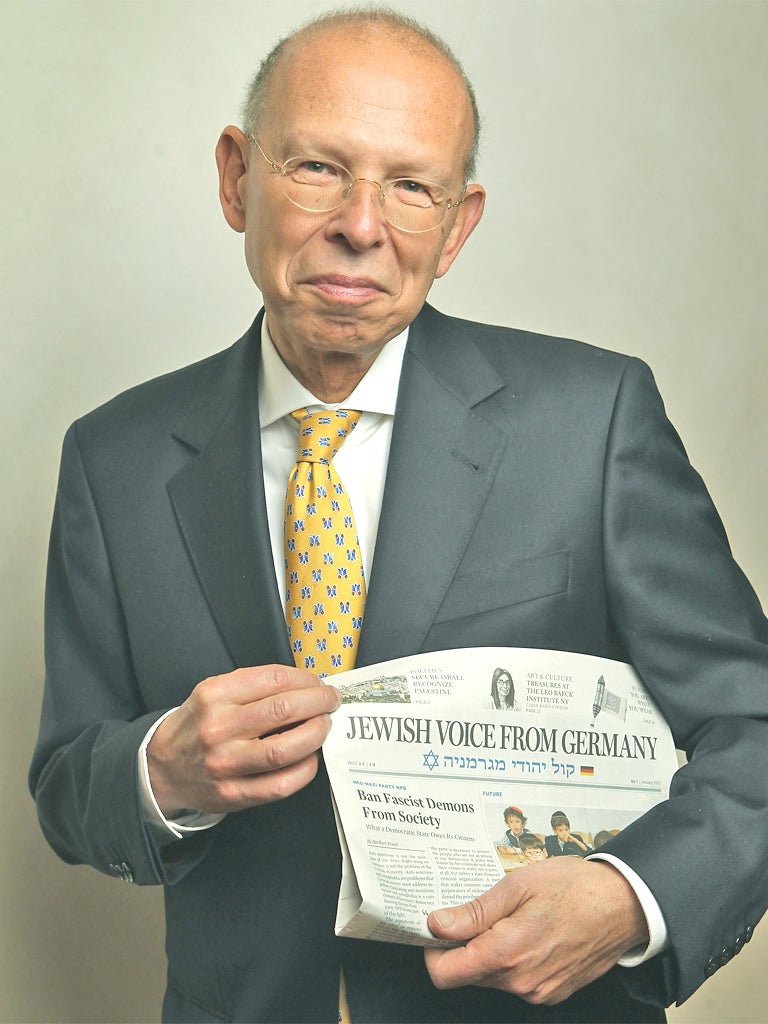

Rafael Seligmann: 'I didn't want Hitler to have the last word'

He lost family in the Holocaust, but one German Jew is fighting back, in print

Rafael Seligmann has reasons enough to despise, if not loathe, the Germans. The Nazis murdered his aunts and uncles. At school in post-war Munich, his teachers boasted that Hitler was a "brave soldier" and his first German girlfriend's parents said his relationship with her "defiled" the German race.

With experiences like these in his luggage, it might seem remarkable that 64-year-old Mr Seligmann – who happens to be both German and Jewish – has just launched an English-language Jewish newspaper from Berlin, which is intent on showing the rest of the world how in Germany, Jewish life is enjoying an extraordinary renaissance.

"My own life as a German Jew brought up in post-war Germany and the dramatic changes in Jewish life that have occurred since the fall of the Berlin Wall prompted me to start the paper," Mr Seligmann told The Independent. "I was adamant that Hitler should not have the last word on German-Jewish history."

Jewish Voice from Germany was launched at the beginning of January. The paper claims to have a readership of around 150,000 with the bulk in the United States and the remainder spread across Britain, Canada, Australia and Germany. It contains a broad cross section of contributions from independent commentators and journalists, many of whom are not Jews.

The first edition features a front-page article by a well known liberal (non-Jewish) journalist calling for a ban on Germany's neo-Nazi National Democratic Party. It also contains a commentary by the Israeli historian, Moshe Zimmermann, proclaiming pessimistically that there will be "no rebirth of German Jews", and a piece by a young Israeli Berliner celebrating the arrival of young Israelis in the German capital.

The paper is published four times a year and Mr Seligmann, a well-known German author, newspaper and television journalist, funds it himself with the help of advertising and subscription fees. He says the project is an attempt to reflect the way Jewish life has begun to flourish in Germany in a way never deemed possible.

"Few dreamt that this would ever

happen. It may not be the same as it was before the Second World War – it may never be like that again," Mr Seligmann says. "But now there are Jewish doctors, scientists, academics and journalists coming to the fore. Jews are becoming a recognisable part of modern German society again."

Before Nazi rule, there were about 600,000 Jews living in Germany. By the time the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989, their number was down to a mere 30,000. Most of them were either Holocaust survivors or – like Mr Seligmann – their children. The majority, who lived in capitalist West Germany, belonged to what was almost a token community dedicated to keeping alive the memory of genocide. The tiny Jewish minority living in East Germany were used as useful propaganda for the country's communist rulers who boasted that their presence proved they had exorcised Nazism forever.

Then in 1990, the government of reunified Germany made what may be regarded as one of its most significant acts of atonement for the Holocaust: it declared immigration a right for anyone able to prove that they were Jewish. The upshot has been an unprecedented influx of Jews from the former Soviet Union and many have even come via Israel. Nowadays, the number of Jews in Germany is estimated at more than 200,000 and rising. It includes about 20,000 Israelis who have settled in Germany, which now has the only growing Jewish population in the world.

It is a far cry from 1957, the year in which Mr Seligmann, aged 10, arrived in Germany for the first time. His parents were both German Jews who had fled Nazi rule and escaped to Palestine before the war. His mother's brothers and sisters did not escape. They perished in the death camps.

By the mid-Fifties, Mr Seligmann's father, a clothing salesman who had never fully adjusted to life in what was by now Israel, decided to move back to Germany with his family. The young Mr Seligmann was told by his father, "You will like Germany" – a phrase which has remained with him ever since: he later used as the title of his autobiography.

For a long time "liking Germany" was something Mr Seligmann found difficult, if not impossible, to do. "I was dreadfully unhappy," he recalls. The Germany of the late-Fifties and Sixties was a country still heavily infected with the poison of Nazi-inspired anti-Semitism. When Mr Seligmann was beaten up by fellow pupils at school, his mother complained to the headmaster. His advice was: "If you don't like it here, take your boy and go back to Palestine." His history teacher told him that Hitler was a "brave soldier who volunteered to fight for Germany". His Nazi party merely wanted to "restore Germany's greatness" and end the "blackmail" the country suffered under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

The doses of Nazi ideology were not only dished out at school. The parents of his first German girlfriend let it be known that they considered Mr Seligmann's relationship with her "defiled" the purity of the German race. When, several years later, Mr Seligmann published his first novel, Rubinsteins Versteigerung (Rubinstein's Auction) giving a warts and all account of his life in post-war West Germany, he found himself under attack from the Jewish community.

"Nobody would publish the book at first. Its Jewish critics even used a Nazi propaganda term: they called me a 'Nestbeschmutzer' – somebody who fouls his own nest," Mr Seligmann says.

It could be argued that even today, reunited Germany has still not got all that much to be proud of when it comes to shedding the influences of Nazism. Neo-Nazi violence has increased massively since reunification. The majority of Germany's new Jewish immigrants are not openly acknowledged as such. Instead they are almost universally referred to as "Russians". Only five years ago, Daniel Alter, the first rabbi to be ordained in Germany since the Holocaust, said he felt more comfortable wearing a baseball cap over his skull cap in public because he feared being identified as a Jew.

Nevertheless, most Jews, including Mr Seligmann, say they live in relative safety in Germany, even if every synagogue and Jewish school in the country is under a constant police guard.

Mr Seligmann says that the most important change wrought by Germany's new generation of Jews is that they are dispensing with the negative perception of themselves as victims. "They feel much easier about expressing themselves than Jews did two decades ago," he says. "In Germany, perhaps more than anywhere else, Jews should be allowed to become as self-confident as anyone else in society."

Jewish Voice from Germany and the man behind the paper are evidence enough that such ideals are being realised. "Fifty years ago I was afraid of the Germany of the Nazis that murdered the Jews," he writes in his autobiography. "Nowadays I feel as if I have found my place among these people as they have with me."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies