Editor’s Note: “Battery-powered brain,” a report by CNN’s chief medical correspondent Dr. Sanjay Gupta, premieres on CNN Presents, Sunday, April 15, at 8 p.m. ET. Gupta is also an assistant professor of neurosurgery at Emory University’s School of Medicine.

Story highlights

For 40 years, Edi Guyton suffered from debilitating depression

She volunteered to have electrodes implanted into her brain

Dr. Helen Mayberg pioneered research to use "deep brain stimulation" on depression

She is now hoping for FDA approval for the method

The first time Edi Guyton tried to commit suicide, she was 19 years old, wracked with depression and unable to deal with the social and academic pressure of college.

Even as a little girl, Guyton never seemed happy. Her mother had encouraged her to smile, but she didn’t see any reason to. In her mind, everyone who smiled was “faking it.”

She often thought about taking her own life, and one night in her college dorm, Guyton’s dark thoughts gave way to action. With a razor blade, Guyton cut one wrist, then the other.

“I think I wanted it to get better or I wanted to die,” she said. “The point was that everything was so bad, I wanted people to know that it was controlling me.”

Her depression controlled her life for the next 40 years – until she decided to volunteer for an experimental treatment. A neurosurgeon would drill two holes in Guyton’s skull and implant a pair of battery-powered electrodes deep inside her brain.

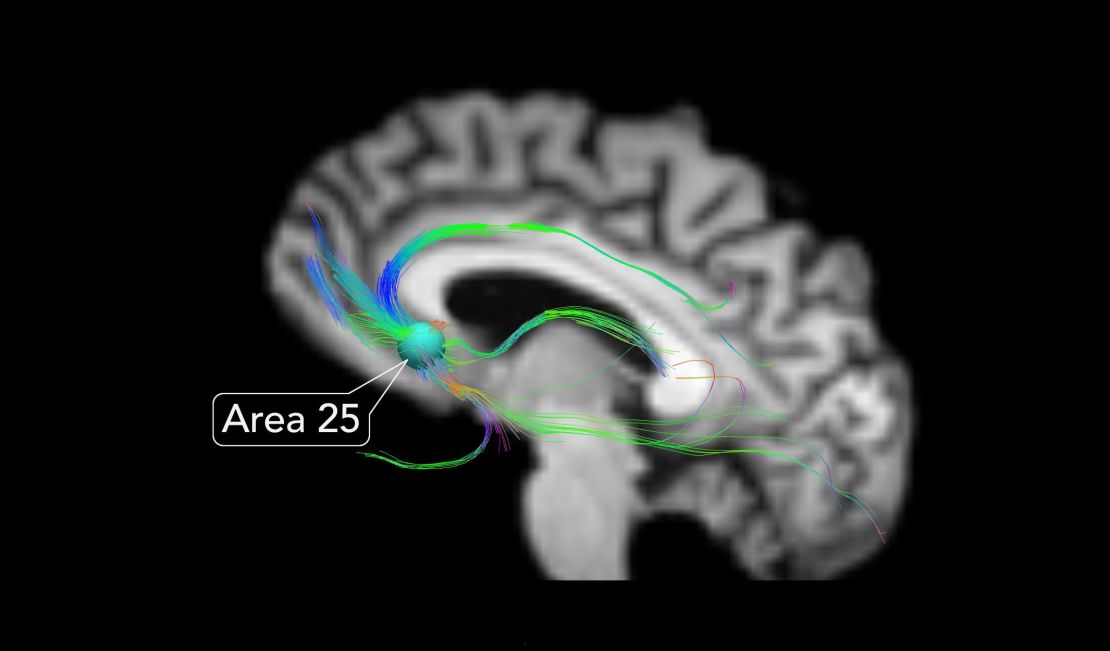

The procedure – called deep brain stimulation, or DBS – targets a small brain structure known as Area 25, the “ringleader” for the brain circuits that control our moods, according to neurologist Dr. Helen Mayberg.

Mayberg’s groundbreaking research on this part of the brain showed that Area 25 is relatively overactive in depressed patients. So, Mayberg hypothesized that in patients who do not improve with other treatments, Area 25 was somehow stuck in overdrive.

Mayberg published the results of her brain scan studies in 1999, the same year Edi Guyton attempted suicide again – this time an overdose of prescription meds that were supposed to ease her depression.

“It’s not that you won’t be happy or that you aren’t happy; it’s that you can’t be happy,” Guyton said.

The first patients

Four years after publishing her research, Mayberg was ready to try what had never before been done: applying deep brain stimulation to Area 25.

DBS had been used since 1997 as a treatment for movement disorders, including essential tremor, Parkinson’s disease and dystonia. Mayberg theorized the low voltage current from DBS could also help severely depressed patients.

Her first surgical experiment in 2003, in collaboration with neurosurgeon Dr. Andres Lozano at Toronto Western Hospital in Canada, was more about testing for safety than actually treating the patients.

“For all we knew, we were going to activate [the circuits] and actually make people feel worse,” Mayberg explained.

The six patients who volunteered for the procedure had all tried and failed conventional treatments. Some had attempted or considered suicide.

“We had patients who were profoundly without any options and suffering,” she said.

All six were lightly sedated when the holes were drilled and the electrodes implanted, but they were awake to describe what they experienced. Several patients reported profound changes just minutes after the stimulator was turned on. One said the room suddenly seemed brighter and colors were more intense. Another described heightened feelings of connectedness and a disappearance of the void.

The patients’ descriptions during the procedure went far beyond anything the doctors expected.

One patient spontaneously talked about the first crocus blooms in early spring. Mayberg wondered if the procedure had triggered a hallucination or perhaps the electrode had touched a memory circuit. The patient explained it’s the feeling of looking forward to something new and rejuvenating.

Mayberg says she struggled to remain a dispassionate scientist, but her empathy for the desperate patients who were, in effect, collaborators in the experiment got the best of her.

“I did a lot of crying,” she said.

After six months of stimulation, four of the six the patients were significantly better. Mayberg has since reported similar results for 31 other patients.

Mayberg and Lozano published the results of that first DBS experiment in 2005, the same year Edi Guyton’s depression subverted her career.

‘I felt nothing’

For years, Guyton had thought she could outrun her despair by working hard. She had earned her Ph.D. while raising two daughters, landing a tenured position as a professor, earning accolades and awards for her teaching and research, and ultimately becoming chair of Georgia State University’s early childhood education department. She said she got there by “faking it.”

“I was the great pretender,” Guyton said.

Then, after 22 years working at GSU, she told her boss and colleagues about her struggle with depression and retired from the job she loved. Still not fully grasping the nature of her illness, she blamed herself.

“After all, what do I have to be depressed about?” she thought.

She tried a variety of treatments, including talk therapy and psychiatric medicines, but nothing worked.

For the next several years, nine sessions of electroconvulsive therapy kept her stable. “I didn’t like it, but it worked,” she said. “But then I went back down. And I went back down very deep.”

With the support of her husband, Guyton managed to stay in the fight. She inquired about the experimental DBS procedure being offered by Dr. Helen Mayberg and her colleague, psychiatrist Paul Holtzheimer, at Emory University in Atlanta.

Mayberg remembers the first time she saw Edi Guyton. Her slow movements were “like being in a muck,” an obvious sign of severe depression, she said. “You could pick her out of a line up.”

Seventeen patients out of more than 1,000 who had inquired were ultimately selected for the experiment. Ten of them, including Guyton, had major depressive disorder and the seven others had depression as a result of bipolar disorder.

The doctors warned them all that the procedure carried the risks of any other brain surgery, including brain damage and death, and no guarantee the depression would lift. Guyton signed the consent form, feeling that she had little to lose.

“It was that bad,” she said.

She could not even bond with her family. The most vivid example was visiting her baby grand-niece. Guyton could barely go through the motions.

“Somebody handed her to me and I held her, but I didn’t even put her face to mine,” Guyton said. “I just held her because I thought, ‘This is what a great-aunt does. She holds the child. She admires the child. And then, thank God, she gives the child back.’ And I felt nothing. Nothing.”

A new lease on life

On February 23, 2007, Guyton rolled into a surgical suite, propelled by a sweet and sour mixture of hope and hopelessness. Her head was mounted in a rigid frame as the doctors studied computer-enhanced images of her brain.

Dr. Robert Gross, the neurosurgeon, began drilling the holes in her skull.

Edi clenched her teeth. “The tears came,” she says. “The sound of the drill, the feeling of it: Not painful, just like somebody’s touching you. That was, I think, what kind of woke me up and said this is your brain that is being drilled into. Somebody is going into your brain.”

The two holes allowed Gross to insert hollow tubes called cannulas, which created a pathway for the DBS electrodes – one on each side of the brain. The electrodes are 1.27 millimeters in diameter, “about the thickness of angel hair pasta,” Gross explained.

As they position the electrodes, the doctors are able to monitor the sound of neurons firing. The gray matter makes a raspy sound. The white matter is silent. And that’s where the sweet spot seems to be: the white matter slightly below Area 25.

Each electrode has four contacts. Each contact can be independently controlled, on or off, with various levels of electricity. Typically, the doctors apply about a thousandth of the power that’s used in a flashlight bulb. At the target, it stimulates approximately 1 cubic centimeter of brain tissue, “about the size of a pea,” according to Gross.

Finding which contact works best is done through trial and error as the patient describes what feels best. As a benchmark, the doctors asked Guyton to rate her feelings of dread on a scale of 1 to 10.

“Eight,” she reported.

Two minutes later, with contact No. 1 on, Guyton said, “Three.”

But doctors would get an ever better result with contact No. 2.

Shortly after the second contact was turned on, Guyton quietly announced, “I almost smiled.” Then she chuckled.

Dr. Holtzheimer asked, “Did something strike you as funny? Or was it just sort of spontaneous?”

“I was thinking about playing with [grand-niece] Susan,” Guyton replied. “That was when I almost smiled. But when I laughed, that was because I almost smiled.”

She had imagined holding the child and looking into her face. “I felt feelings that I thought were gone,” she would later say.

How did it feel to have a machine and electricity transform her emotions?

“It felt fantastic,” she said. “I didn’t care what was doing it!”

To determine whether the surgery was truly effective or if the patients felt better simply because they believed in the treatment, the doctors told the patients that some of the battery packs powering the electrodes inside their brains would be turned off, while others would be left on, to measure any placebo effect.

Guyton’s power pack was turned off, and her depression quickly returned. With the stimulator back on, she improved.

Based on her scores in February from a widely used psychological test called the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Guyton’s mental illness is in remission. Her ups and downs are the same that any healthy person would experience – as long as the battery in the stimulator implanted under her collarbone remains charged.

Five years after the surgery, Edi Guyton is one of Mayberg’s most dramatic success stories. She volunteers with a mental health advocacy group, she’s active with a church and she’s in a writer’s club. And last fall she toured Italy with college friends who knew her from the days she had put a razor to her wrists.

To be sure, Guyton still has some bad days. “I don’t feel good all the time,” she admitted, and she sometimes worries that a bad spell could be lurking on the horizon. “But this gives me the capacity that if I can, if there is joy in my life, I have the capacity to feel it.”

Next steps

As much as Mayberg’s experiments showcase how far brain science has advanced, there is still much more to learn. In fact, more than 10 years after her pioneering studies on Area 25, Mayberg is still trying to answer basic questions about the experimental treatment she conceived. Does the electricity from DBS activate neurons near Area 25 or inhibit them? Is DBS flipping a switch or knocking down a wall?

“To be brutally honest, we have no idea how this works,” Mayberg said.

Mayberg is the co-holder of a patent for the procedure, which has been licensed to St. Jude Medical, Inc., a company that manufactures and sells DBS equipment. St. Jude is hoping to win Food and Drug Administration approval for commercial use of DBS for treatment-resistant depression.

The FDA awarded limited approval in 2009 to Medtronic, Inc., to use DBS on a different part of the brain for intractable obsessive compulsive disorder. Medtronic is funding a study to determine if that part of the brain, the ventral capsule/ventral striatum, could also be a viable target for depression.

In the meantime, Mayberg still hopes to answer why DBS helps some patients but not others. After all, if Area 25 is the “ringleader,” why doesn’t everyone improve? Mayberg simply does not know.

“We’ve got to understand the biology better,” she says. “So until we’re actually hitting 90% or really effectively helping everybody, we’ve got our work cut out for us.”