Tune in to “Anderson Cooper 360°” all week for the surprising results of a groundbreaking new study on children and race at 8 and 10 p.m. ET.

Story highlights

AC360° commissioned a groundbreaking study on children and race

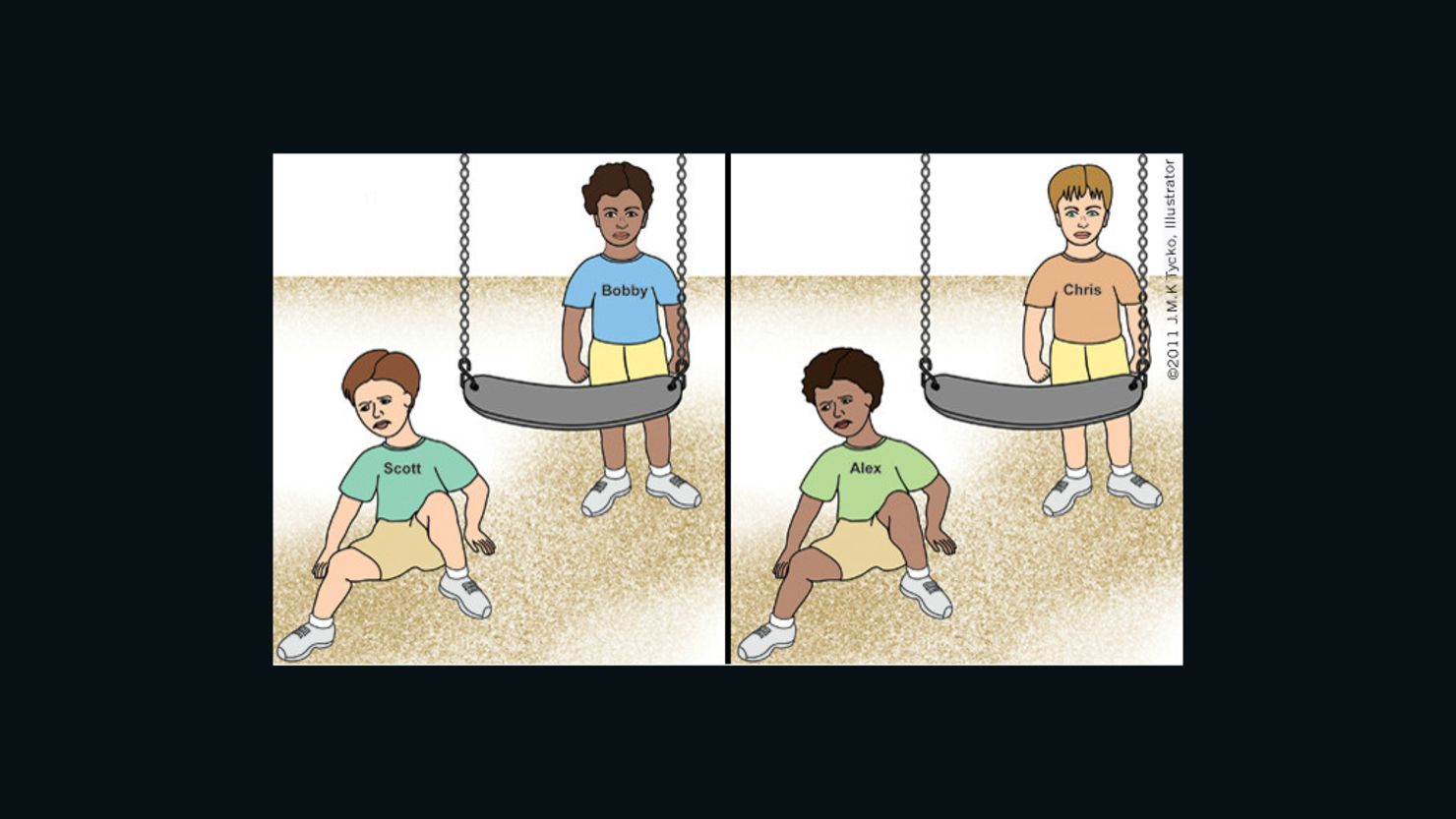

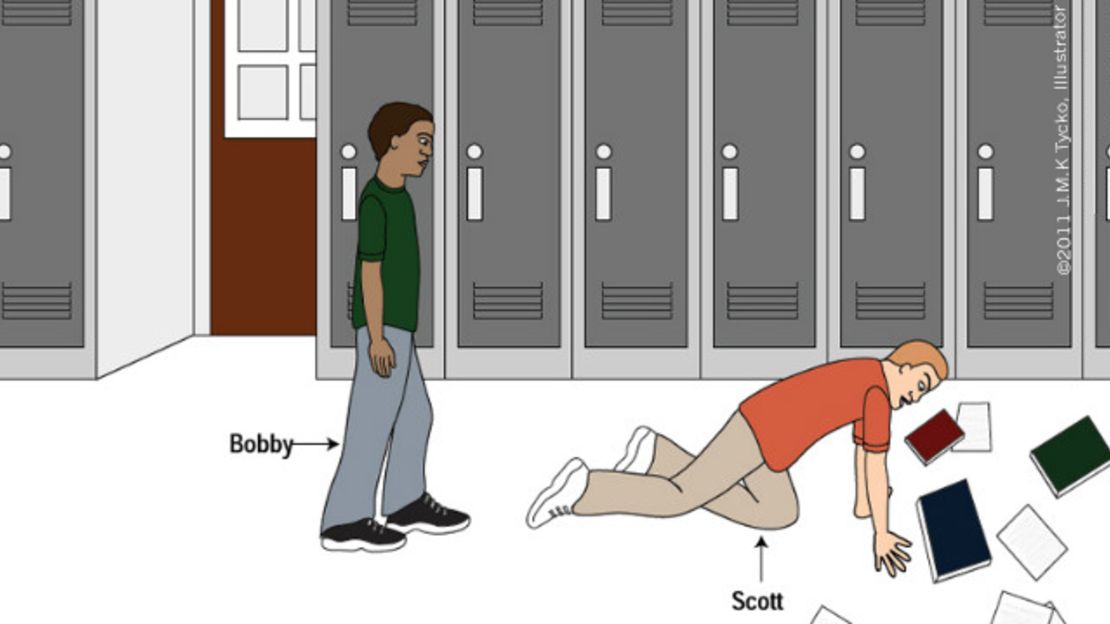

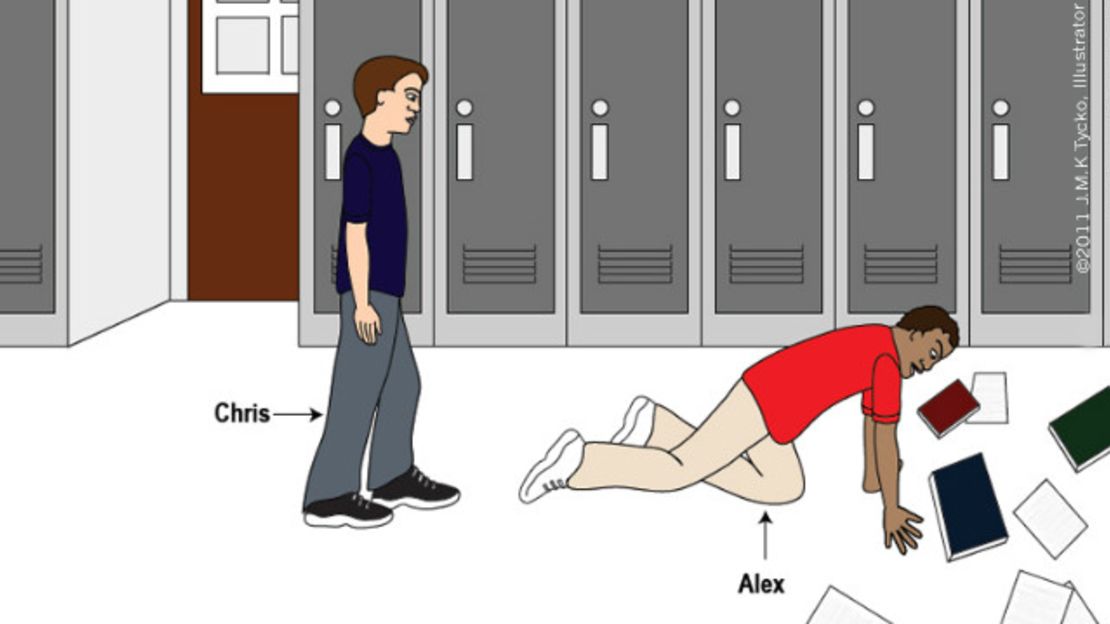

White child and black child looked at the same picture of two kids on a playground

Black first graders had more positive interpretations than white first graders

Psychologist says divide often starts with how parents talk to kids about race

A white child and a black child look at the exact same picture of two students on the playground but what they see is often very different and what they say speaks volumes about the racial divide in America.

The pictures, designed to be ambiguous, are at the heart of a groundbreaking new study on children and race commissioned by CNN’s Anderson Cooper 360°. White and black kids were asked: “What’s happening in this picture?”, “Are these two children friends?” and “Would their parents like it if they were friends?” The study found a chasm between the races as young as age 6.

Overall, black first-graders had far more positive interpretations of the images than white first-graders. The majority of black 6-year-olds were much more likely to say things like, “Chris is helping Alex up off the ground” versus “Chris pushed Alex off the swing.”

They were also far more likely to think the children pictured are friends and to believe their parents would like them to be friends. In fact, only 38% of black children had a negative interpretation of the pictures, whereas almost double – a full 70% of white kids – felt something negative was happening.

But why? CNN hired renowned child psychologist and University of Maryland professor Dr. Melanie Killen as a consultant to design and implement this study. She says the divide often begins with the different ways parents talk to their kids about race.

“African American parents … are very early on preparing their children for the world of diversity and also for the world of potential discrimination,” said Killen, adding, “they’re certainly talking about issues of race and what it means to be a different race and when it matters and when it doesn’t matter.”

In contrast, the negativity for white children could be more of a result of what parents are not saying to their children than what they are saying. Dr. Killen contends that white parents often believe their children are socially colorblind and race is not an issue necessary to address. “They sort of have this view that if you talk about race, you are creating a problem and what we’re finding is that children are aware of race very early,” said Killen.

Read full “Kids on Race” study (PDF)

That racial void left by parents is filled with all of the overt and subtle messages on race from the rest of society – what children see and hear from their teachers and friends, TV shows they watch, and what they’re exposed to online all have a profound and lasting effect. Killen also points out that parents can send silent subconscious messages about race to their children that have a big impact.

“When …we’re in a situation in public, we’re in a room, and we have the opportunity to ask two different people for help … we might just you know be more likely to ask the person of the same race than somebody’s who’s in opposite race for help.” Killen uses it as an illustration of an everyday interaction that can send an unintended message to children.

The study found that black children’s optimism about interracial friendships unfortunately fades by adolescence. Killen and her team also tested 13-year-old children and showed the teens similar pictures designed to be ambiguous.

While black children start out positive, by age 13 they become as pessimistic as white kids. Dr. Killen says experiences of rejection and the harsh realities of race relations most likely explain the trend.

Dante, a black teen, told the heartbreaking story of racial bullying so severe, he had to change schools. “I’ve been bullied for like the way I look and the way of my skin at my previous school …and they just kept on bullying me and … I just asked them to stop over and over again and then I tried not to break, like, but I couldn’t hold on anymore,” said Dante, adding, “so I asked my mom, ‘Can I leave?’ “

Jimmy, another black teen, talked of a white friend’s mother forbidding her son to play with him because he was black. Jimmy said when his mother questioned the woman, she spelled it out in no uncertain terms, saying, “It’s because you’re black so we can’t hang out.”

Are we doing enough to teach kids about race?

Both teens told their stories in an open-ended question session, conducted by Killen and her team, at the request of CNN to fully understand how children’s racial views are shaped. Killen says stories like these represent a painful reality check on race for black children. “(If children) have that kind of experience and you have that repeatedly over a number of years, I think it’s adaptive to pull back,” she said, adding, “I think your optimism is going to decline because you’ve been told you know you really don’t belong here or you’re really not part of us .”

The CNN study had a key piece of good news for children of all ages. The racial makeup of a school can play a dramatic role on kids’ attitudes on race – especially with white children. Both white and black students were tested at three types of schools – majority white, majority black and racially diverse. White students at majority white schools were overwhelmingly the most negative, but there was a seismic decrease in that negativity among white kids at the other two types of schools.

The reason, according to Dr. Killen, is about friendships. “There’s almost nothing as powerful as having a friend of a different racial ethnic background to reduce prejudice, to … have that experience that enables you to challenge stereotypes,” she said.

Samantha, a white teen at a majority black school, epitomized that finding. “My grandparents are very racist against African Americans and other races. It’s 2012, they have to push that aside … they say, ‘You want to stick with your own race.’ And I say, ‘No, I’m friends with everyone.’ ”

Watch Anderson Cooper 360° weeknights 8pm ET. For the latest from AC360° click here.