They have entranced generations with the beauty of their songs and glimpses of their plumage. But today the sound of the linnet and the vision of a turtle dove are becoming increasingly rare experiences for visitors to the European countryside.

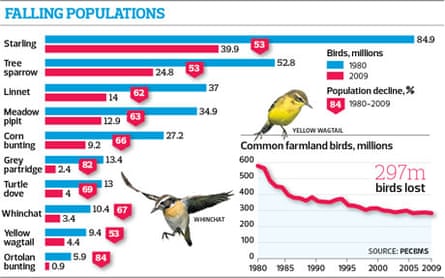

Indeed, according to a new survey, the chances of encountering any one of the 36 species of farmland birds in Europe – species that also include the lapwing, the skylark and the meadow pipit – are now stunningly low. Devastating declines in their numbers have seen overall populations drop from 600 million to 300 million between 1980 and 2009, the study has discovered.

This dramatic decline represents a 50% reduction and is blamed on major changes in farming policies enforced by the EU over the last 30 years.

In order to boost food production across Europe, the wholesale ripping up of hedgerows, draining of wetlands and ploughing over of meadows has robbed farmland birds of their homes and food. Numbers of linnets, turtle doves and lapwings have crashed as a result.

The survey, carried out by the Pan-European Common Bird Monitoring Scheme, also found that Britain has been one of the nations worst affected by losses to its farmland bird populations. For example, in Europe the population of grey partridges has dropped from 13.4 million to 2.4 million, a loss of 82%. In the UK, that loss was 91%.

These losses were described as shocking by the scheme's chairman, Richard Gregory. "We had got used to noting a loss of a few per cent in numbers of various species over one or two years. It was only when we added up numbers of all the different farmland bird species for each year since 1980, when we started keeping records, that we found their overall population has dropped from 600 million to 300 million, which is a calamitous loss. We have been sleepwalking into a disaster."

According to Gregory, who also serves as the head of species monitoring for the UK's Royal Society for the Preservation of Birds (RSPB), a range of factors are involved. In the case of the grey partridge, he blamed the intensification of farming which had killed off the plentiful numbers of insects that they ate.

With starlings, whose populations have fallen from 84.9 million to 39.9 million, a drop of 53%, it has been the destruction of woodlands and the corresponding loss of nesting places that has done the most serious damage, he said.

"By contrast, lapwings – whose numbers have declined from 3.8 million to 1.8 million, a drop of 52% – are more associated with marshes and riverbanks. It has been the draining of these lands that has destroyed their habitats and reduced their numbers so drastically."

However, the RSPB was emphatic that individual farmers should not take the blame for the devastating drop in farmland bird numbers that has occurred over the past 30 years.

"The decline of farmland birds across Europe has been one of our greatest wildlife tragedies but it is important to remember they have been driven by farming policy rather than farmers themselves," said Jenna Hegarty, the society's senior agricultural policy officer. "We work with thousands of farmers across the UK who are striving to put wildlife back on the land, but farmers cannot do this without significantly increased funding for more environmentally friendly measures."

The fact that the high losses of linnets, turtle doves and other farmland birds had not been expected was blamed by Gregory on a phenomenon known as the shifting baseline syndrome.

"We take for granted things that two generations ago would have seemed inconceivable – in this case the reduction by 300 million of Europe's farmland bird population," he said. "Apart from the removal of creatures that are beautiful to behold and beautiful to listen to, we should take note of what this means. These losses are telling us that something is seriously amiss in the world around us and the way that we are interacting with nature."

However, it is unlikely that the problem will get better in the near future, he added. In Bulgaria, Poland and the EU's other, newer member nations in eastern Europe, the farming policies that have been responsible for wiping out vast numbers of farmland birds in older member countries are only being introduced today. Once they take effect, overall numbers of farmland birds will drop even further, it is expected. "We need to introduce measures that consider the environmental impact of the agriculture policies we are implementing," said Gregory.

The discovery of the dramatic losses suffered by farmland birds since 1980 comes as the green movement prepares to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring. The book, published in summer 1962, outlined the devastating impact that the uncontrolled use of synthetic insecticides was having on populations of birds in the US and played a critical role in kick-starting the green movement on both sides of the Atlantic.

Humanity was beginning to have a dreadful impact on wildlife and in particular on birds, Carson argued. "A grim spectre has crept upon us almost unnoticed," she wrote. Her words had a major influence.

Silent Spring, which outlined dozens of examples of the widespread slaughter of birds, led directly to the banning of the manufacture of DDT and other pesticides. However, the bird losses she outlined 50 years ago have been dwarfed by the losses that have occurred in the last 30 years and which are revealed in the RSPB survey. As the environmental campaigner Jonathon Porritt put it: "I think Carson would be horrified about the state of the planet today."

Farmland species under threat

GREY PARTRIDGE

Numbers across Europe have fallen by 82%, from 13.4 million to 2.4 million, but the decline is markedly higher in Britain at 91%.

WHINCHAT

A summer visitor whose breeding grounds are in upland parts of northern and western Britain. Its population has fallen by67%.

YELLOW WAGTAIL

Breeds in a variety of habitats in the UK, including arable farmland, wet pastures and upland hay meadows. Numbers down by 53%.

LAPWING

Also known as the peewit in imitation of its display calls, its proper name describes its wavering flight. Numbers are down by 52%.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion