Story highlights

Health care spending for children growing fastest, report says

Consumer out-of-pocket spending for child health care rose 7% from '09 to '10

Families of children with chronic illnesses say they're being hit hard

Heather Bixler wishes she could undo the moment she’s relived countless times: She was leaving her New York apartment with her 4-year-old daughter and infant son, who was in a baby carriage. It was May 2, 2003, and they were going to rent a movie.

The doorman, perhaps just to play around, picked up the stroller and held it almost vertical. Sean, the baby, fell out. His head bashed against the marble stair.

Sean’s skull was fractured, and he was bleeding internally. The incident left him with scar tissue in his brain.

Two years ago, the seizures started. So did the never-ending medical expenses.

The Bixler family is just one example of how a child’s chronic illness can strain a family emotionally and financially – and children represent the fastest growing health care spending group in America, according to a new report.

Bixler is a professional violinist, her husband teaches music at a local college; they now live in Bowling Green, Ohio. Their children are covered under his insurance, but the coverage doesn’t include everything Sean needs to be healthy – they could end up paying $50,000 or more this year alone, depending on what their insurance ends up covering.

And Sean’s mother can’t work because someone needs to be with Sean at all times. She estimates that between 30% to 50% of the family income goes toward care for Sean; most of the costs have been out-of-pocket.

“I have put my life on hold,” says Bixler, 47. “I’ve depleted my entire savings account, pretty much,” she said.

When Sean started having seizures, Bixler took him to a neurologist, who diagnosed epilepsy. Insurance covered 80% of the procedures required to make that determination, but that still left the Bixlers with about $1,500 to pay out of their own pockets.

The boy’s condition worsened last fall, when Bixler started pursuing a college degree in Memphis that required her to leave their Ohio home for half the week.

“He started having seizures all the time, sometimes six a day, gran mal seizures that would last a couple minutes, and would be so bad that a couple times I called the ambulance because he was turning blue and stopped breathing,” Bixler said.

If someone wasn’t right by Sean’s side during a seizure, he would fall. Once, he was holding a glass in his hand, it broke, and he fell into the shards, slashing the side of his head.

“He had to be watched constantly. And if he wasn’t being watched, like if I had to take a shower, I would make him sit in a cushioned armchair and tell him, ‘You can’t move,’” she said. “It was more work than when he was a baby.”

They tried another neurologist. Different medication. Alternative medicines.

As the seizures got worse, so did the child’s ability to communicate. Sean had been an “unusually smart” until recently; he could tell you names of complicated dinosaurs, Bixler said. He was talented at art and would draw so much that Bixler couldn’t keep all of his works. But in January, Sean’s teacher told Bixler that Sean had failed a spelling test.

In February, he couldn’t read his own birthday cards. He lost the ability to answer basic questions – even “What’s your name?” Sometimes he couldn’t even talk beyond “hi Mom” and “I love you.”

A $31,000 visit to the Cleveland Clinic determined that the seizures are connected to that scar tissue that formed after Sean hit his head on the marble stair. Bixler’s insurance company initially told her that that expenditure wasn’t necessary; Bixler fought back, and is waiting to see how much of it will be covered. The family is fund-raising for Sean through the website giveforward.com.

She’s now paying about $100 per week more for groceries because she has put her son on the ketogenic diet – a strict high-fat, low-carbohydrate regimen – that has helped reduce seizures for other children with epilepsy. On Tuesday, Sean’s first day on the diet, he suffered a couple of seizures, but as of Friday he hadn’t had any others. And he actually was able to read a page of a book – although slowly and painstakingly.

“I’m trying to work with him to try to get him to read again, and then eventually we’ll try to do some math,” Bixler said.

Families like the Bixlers are always paying attention to the math of adding up medical bills.

Health care expenses growing fastest among children

A report released Monday from the Health Care Cost Institute, details how out-of-pocket health care expenses are on the rise, and spending in general is growing fastest among Americans 18 and under.

The institute is an independent nonprofit research organization that partnered with four major insurance companies (Aetna, Kaiser, United and Humana) to analyze 3 billion insurance claims of people with group employer-sponsored health insurance.

The study said consumers’ out-of-pocket expenses rose 7% from 2009 to 2010, according to the institute. For insurers, costs only rose 2.6% during that time period.

Per person under 65, the average annual spending on health care was $4,255 – that’s a combination of what people and their insurance companies paid.

Between 2009 and 2010, it rose 4.5% for Americans under 18. The trend has been upwards for children since 2007, when the average annual expenditure for this group was $1,790, compared to $2,123.

Older Americans still spend more in absolute terms, however. The 55 to 64 age group spent $8,327 in 2010, a 3.1% increase over the previous year.

Prices rising

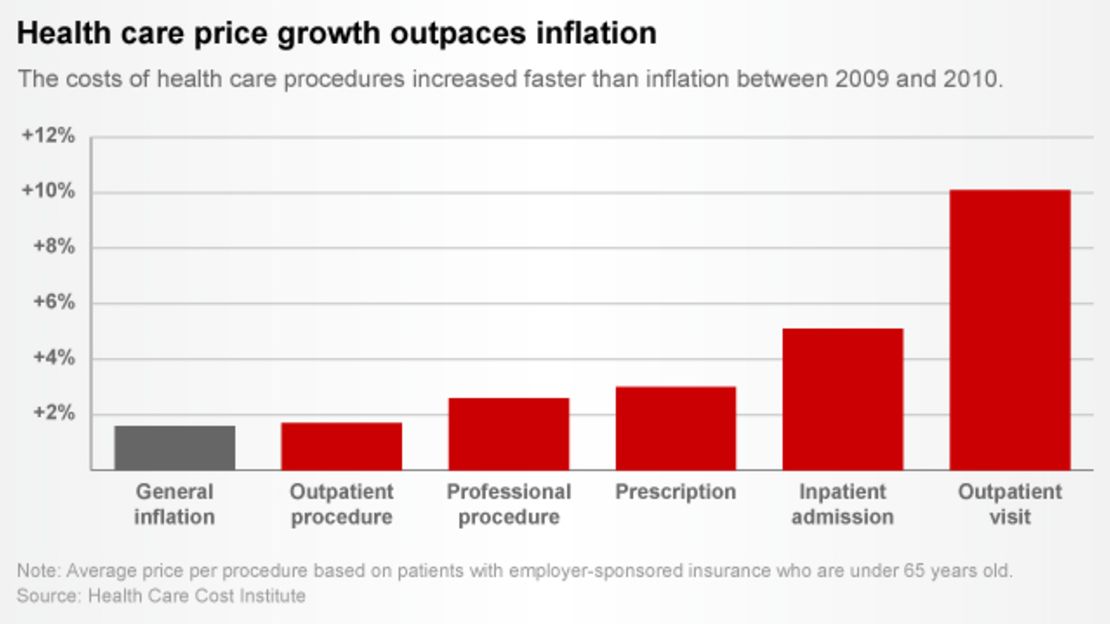

What is driving the trend in health care expenditures? The report suggest that it’s prices. The average facility price for an emergency room visit grew 11% from 2009 to 2010 ($1,327). Average inpatient surgical admission prices rose 6.4%; outpatient surgery prices rose 8.9%.

If her family didn’t have insurance, Bixler has no idea what she would do – perhaps declare bankruptcy.

Tammy Davenport, 38, laughs when she thinks about what would happen if she lost the health insurance she’s getting through her job. Her son’s medication alone costs $65,000 per month before insurance. In theory, she’d have to bear that burden – in reality that would be impossible. Like the Bixlers, she’s given up a lot for the sake of her chronically ill child.

Davenport’s 17-year-old son Garret has a bleeding disorder called hemophilia. So does Davenport. Because people with hemophilia take a long time for their blood to clot, minor injuries can result in major trauma.

Expenses are going up all the time. Her deductible three years ago was $500 per person, now it’s $1000.

When Garret was very young, Davenport worked in daycare, partly so that he could be with her during the day. She also substitute-taught for awhile, another profession that allowed her the flexibility of spending a week in the hospital with her son if he had an accident.

Davenport never got to go for a bachelor’s degree; her ex-husband never finished his.

“I think anybody with a chronic illness has to make certain decisions in order to make sure they have health care coverage,” she said. “Sometimes you sacrifice food, sometimes you sacrifice living in a decent house, driving a decent car, just to make sure your kids are taken care of.”

Davenport works at a specialty pharmacy where she takes care of people with bleeding disorders. Families that include individuals with bleeding disorders tend to be low-income, Davenport said.

“It’s not normal for a family to be able to have a nice life, not have to worry about insurance and know their kids are going to be taken care of, it just doesn’t happen,” she said. “You spend your time sacrificing everything else to make sure that their medication is available to them.”