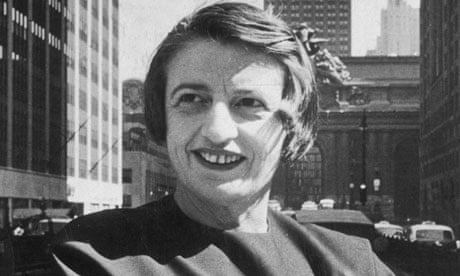

As an atheist Ayn Rand did not approve of shrines but the hushed, air-conditioned headquarters which bears her name acts as a secular version. Her walnut desk occupies a position of honour. She smiles from a gallery of black and white photos, young in some, old in others. A bronze bust, larger than life, tilts her head upward, jaw clenched, expression resolute.

The Ayn Rand Institute in Irvine, California, venerates the late philosopher as a prophet of unfettered capitalism who showed America the way. A decade ago it struggled to have its voice heard. Today its message booms all the way to Washington DC.

It was a transformation which counted Paul Ryan, chairman of the House budget committee, as a devotee. He gave Rand's novel, Atlas Shrugged, as Christmas presents and hailed her as "the reason I got into public service".

Then, last week, he was selected as the Republican vice-presidential nominee and his enthusiasm seemed to evaporate. In fact, the backtracking began earlier this year when Ryan said as a Catholic his inspiration was not Rand's "objectivism" philosophy but Thomas Aquinas'.

The flap has illustrated an acute dilemma for the institute. Once peripheral, it has veered close to mainstream, garnering unprecedented influence. The Tea Party has adopted Rand as a seer and waves placards saying "We should shrug" and "Going Galt", a reference to an Atlas Shrugged character named John Galt.

Prominent Republicans channel Rand's arguments in promises to slash taxes and spending and to roll back government. But, like Ryan, many publicly renounce the controversial Russian emigre as a serious influence. Where, then, does that leave the institute, the keeper of her flame?

Given Rand's association with plutocrats – she depicted captains of industry as "producers" besieged by parasitic "moochers" – the headquarters are unexpectedly modest. Founded in 1985 three years after Rand's death, the institution moved in 2002 from Marina del Rey, west of Los Angeles, to a drab industrial park in Irvine, 90 minutes south, largely to save money. It shares a nondescript two-storey building with financial services and engineering companies.

There is little hint of Galt, the character who symbolises the power and glory of the human mind, in the bland corporate furnishings. But the quotations and excerpts adorning the walls echo a mission which drove Rand and continues to inspire followers as an urgent injunction.

"The demonstration of a new moral philosophy: the morality of rational self-interest."

These, said Onkar Ghate, the institute's vice-president, are relatively good times for Randians. "Our primary mission is to advance awareness of her ideas and promote her philosophy. I must say, it's going very well."

On that point, if none other, conservatives and progressives may agree. Thirty years after her death Rand, as a radical intellectual and political force, is going very well indeed. Her novel Atlas Shrugged, a 1,000 page assault on big government, social welfare and altruism first published in 1957, is reportedly selling more than 400,000 copies per year and is being made into a movie trilogy. Its radical author, who also penned The Fountainhead and other novels and essays, is the subject of a recent documentary and spate of books.

To critics who consider Rand's philosophy that "of the psychopath, a misanthropic fantasy of cruelty, revenge and greed", her posthumous success is alarming.

Relatively little attention however has been paid to the institute which bears her name and works, often behind the scenes, to direct her legacy and shape right-wing debate.

"We are providing the intellectual ammunition," said Ghate, 42. "We are helping the Tea Party and others to understand what is going on in America, and to understand what the alternatives are. This is an exciting time. A tremendous opportunity."

Intellectuals and policymakers largely scorned or ignored Rand in the 1950s. In the 1960s she was discovered by university students drawn to her radicalism and emphasis on self-reliance. Ayn, they learned, rhymed with mine. Her books became best-sellers and filtered down to high schools.

However, politicians continued to shun her economic and social libertarianism. Democrats resented her attacks on government activism. Republicans chafed at her attacks on Christianity, the Vietnam war and Ronald Reagan, whom she considered a medieval throwback for mixing religion and politics.

A decade ago, said Ghate, the institute struggled for attention. "We were knocking on doors and people were not answering." In the aftermath of 9/11 that began to change. Rand had warned of "Islamist totalitarianism" after the 1979 Iranian embassy crisis, a warning which seemed prescient to the neo-conservatives who cheered the Bush administration's wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The institute, in fact, turned against the wars on the grounds attempted nation-building and democracy-spreading were "misguided altruism" which did not advance US interests. This iconoclastic critique from the right did not change US policy but gained the keepers of Rand's flame respect and credibility, said Ghate, a Canadian of German and Indian parentage with a PhD in philosophy.

With annual revenue of around $8m and 40 staff the institute burrowed deeper into national consciousness, running an undergraduate degree course, sending hundreds of thousands of Rand's books to schools and drawing 20,000 entrants to essay contests with $10,000 prizes. (Last year's entries surged to 29,000.)

And then, in February 2009, came Rick Santelli's televised rant against the Obama administration's mortgage bailout plan, a tirade which endorsed Rand and galvanised scattered anti-government protests into the Tea Party movement. The institute took off along with it.

"There is no formal relationship between us and the Tea Party but we view them as a good phenomenon, a healthy reaction on the part of Americans," said Ghate. Tea Partyers were not the backward dimwits caricatured in the media. "They read and explore ideas. And they think America is headed in the wrong direction. This is a market for us."

The institute supplied intellectual rigour in the form of speakers, commentators and publications to the Tea Party's legitimate "emotional response", said Ghate, whose office has portraits of Rand and Aristotle.

"Obama is taking us further away from capitalism: look at the controls over the financial system, or Obamacare. Instead of freeing the economy he is distorting the market."

He rejected the mainstream view that lax financial regulation fuelled the economic crisis and blamed excessive regulation and spending. This message has found echo in Paul Ryan, a Tea Party favourite who as the senior Republican on the House budget committee proposes sweeping cuts which could be enacted under a Romney administration.

"His budget proposals are better than what anyone else is proposing but I don't think they're good," said Ghate, who wished Ryan would go even further to end the "legalised theft" that is the social welfare system. "Taking money from someone who has earned it and giving it someone who hasn't."

A trickier problem for both sides is Ayn Rand's vocal support for abortion rights and hostility to religion – she considered faith in God a psychological disorder.

Liberal foes, said Ghate, tried to use that as wedge between the institute and Tea Party social conservatives. Some in the movement recoiled upon discovering Rand's Godlessness, he said, but the de facto alliance would survive. "The Tea Party has tried to keep its focus on economic issues. The Republicans and Democrats pander more to religion."

Rather than assail Ryan as a sellout who had abandoned Rand the institute's vice-president struck a conciliatory tone. "It's tempting for any politician to backtrack. His enthusiasm [for Rand] might be a bit more muted than before … but he is still influenced by her."

The institute, said Jennifer Burns, author of Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right, was proving more pragmatic than its late prophet.

"It has evolved very rapidly in the past 10 years and has made efforts to become part of the broader dialogue. It recognises, as Ayn Rand did not, that if you don't compromise you limit yourself to a very limited audience."

In the same vein politicians like Ryan shunned her electorally toxic strands. "In her pure form she'll never be that powerful. Her most successful followers are those who have taken her ideas and blended them with others."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion