Story highlights

A blockage in Patrick Divricean's intestines prevented him from moving his bowels

The rare birth defect called rectal atresia occurs in one out of every 5,000 babies

In the hands of children, strong magnets have proven dangerous, even deadly

Surgeons have used magnets in a variety of ways for treatment

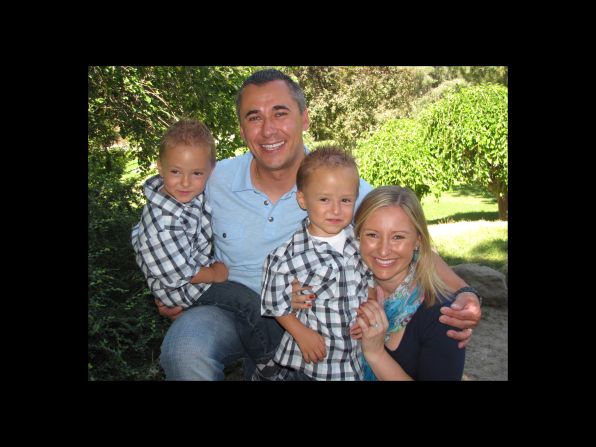

The day after Nelly Divricean gave birth to twin sons Andrew and Patrick, doctors gave her terrible news: one of her tiny, premature babies was in serious trouble.

“Something’s wrong,” the doctors told her. “We think Patrick has a blockage. We need to move him to a different hospital.”

A blockage somewhere inside Patrick’s intestines was preventing him from moving his bowels. Doctors needed to fix it before his intestines ruptured and he died.

Weighing just 4 pounds, Patrick was too small for a major surgery that could solve the problem permanently, so doctors moved him from Salt Lake City’s Intermountain Medical Center to nearby Primary Children’s Medical Center, where a section of his intestines was temporarily diverted into a colostomy bag.

“Because he couldn’t poop, they had to make a way,” Divricean said.

A few months later, Divricean and her husband, Michael, brought Patrick back to his surgeon, Dr. Eric Scaife.

“OK, what do we do next?” she asked him.

Scaife took an X-ray and what he saw wasn’t good. A thin, hard membrane was blocking a section of Patrick’s intestines – the result of a rare birth defect called rectal atresia that occurs in one out of every 5,000 babies.

“We need to remove it,” the doctor told the couple.

Scaife described to Patrick’s worried parents a long, technically difficult surgery. Patrick would be cut open through his abdomen and vertically along his tailbone. Once inside, Scaife would remove the membrane and then piece together two sections of intestines.

He had his concerns. It was a big operation on a little baby. The surgery might cause scarring, or it might injure nerves in Patrick’s pelvis that could lead to incontinence.

If Patrick was Scaife’s son, what would he do? Divricean asked the surgeon.

Scaife told her he’d think on it and give them an answer the next week.

“Hopefully, they’ll come up with something that will save Patrick or will give us a better option at least,” Divricean thought as she waited for the week to pass.

A better option

A week later, Scaife had an idea.

Instead of removing Patrick’s blockage, he wanted to break through it – with two powerful magnets.

In the hands of children, strong magnets have proven dangerous, even deadly. When swallowed, they’ve passed into the intestines, and their attraction to each other has forged a hole in tissues.

It occurred to Scaife that in the skilled hands of a surgeon, magnets might be a useful tool instead of a hazard. If he placed a magnet on either side of Patrick’s blockage, their attraction might make a hole and destroy the membrane, allowing stool to pass.

Scaife’s idea was untested and unproven – but if it worked, Patrick wouldn’t need surgery.

“A magnet’s a wonderful thing,” said Dr. R. Adam Noel, an associate professor of pediatrics at the Louisiana State University Heath Science Center in New Orleans. “They can be used in very clever medicine.”

Surgeons have used magnets to bore drainage holes in intestinal tissue, lengthen the esophagus and straighten dips in chests.

For Scaife’s idea to work, he would need to find the perfect magnets. They had to be strong enough not to slip off the membrane and sized just right to create the hole.

“I’m not quite sure how we get them,” he told the couple.

So the Divriceans went shopping.

“We went to Toys R Us,” Divricean said. “They just had some that were too big.”

A few more toy stores later, not finding what they needed, they realized kiddie magnets weren’t going to cut it. Divricean searched the Internet and bought industrial-strength magnets from an online company.

The couple then made an appointment for Patrick’s procedure.

The procedure: ‘It made sense’

At the hospital, Patrick went back under the X-ray machine. Scaife, along with a radiologist who was helping him, could see the blockage.

What they were about to do next was an experiment. The magnets they wanted to place inside Patrick weren’t approved by the Food and Drug Administration as a medical device, and Scaife knew of no one who had performed the procedure.

“Innovation, even with simple magnets and a pretty simple kind of procedure, is not easy. It’s tricky, so you have to proceed cautiously, even when the parents are saying, ‘Yeah I’d like to do that. It sounds better,’” said Art Caplan, a bioethicist at New York University’s School of Medicine.

“If you’re doing unapproved experiments, or something novel, the risk is enormous, especially with a child.”

Scaife had consulted his colleagues and determined that if the magnets slipped and somehow created a hole in Patrick’s intestines, he would be forced to do the operation he was trying to avoid. Otherwise, he didn’t see a downside to the procedure.

“This certainly did not go through, sort of, formal medical channels,” Scaife said. “But there was very clearly, I think, an informed consent … it made sense to them, it made sense to me, and I think with that kind of clear understanding we proceeded.”

Scaife and the radiologist maneuvered the magnets into position.

“We just dropped the magnets in like coins into a slot, and they immediately clicked together,” he said.

Over the next few days the force of the magnets applied pressure to both sides of the membrane, pinching it and draining it of blood until it weakened and broke.

The magnets had made the hole that Scaife was expecting. They were still connected a week later when Scaife took them out. Sandwiched between them was a wafer-thin disc of membrane tissue.

“We couldn’t believe that that really worked,” Divricean said. “It was just something really amazing.”

After the procedure, Divricean took Patrick into her arms. Holding him, she knew he was spared a complicated, invasive surgery.

“It worked out well – really well – for him,” Scaife said.

The procedure was covered by insurance, Divricean said.

In December 2009, nearly six months after Patrick was born, he had a bowel movement in a diaper for the first time.

“We took pictures of the diaper,” Divricean said, laughing. “We thought we were crazy doing that, but we were so excited.”