Maps are at the centre of a worldwide commercial power struggle this weekend as Apple faces criticism of the technology it has developed for its new smartphone. But two new books and an exhibition at the Royal Geographical Society reveal that maps have been at the centre of both politics and commerce down the ages, as well as key to the development of the human imagination.

In his new book, On The Map, Simon Garfield explains that, just as the empires of the past understood that marking territory was crucial, so Google and its rivals now wield influence. They are even implicated in border disputes. Garfield describes how in 2010 the Nicaraguans cited Google Maps in support of their action when they invaded Costa Rica. Brian McClendon, who developed the mapping technology bought up by Google in 2004, told Garfield that the Nicaraguans argued that they were justified in moving onto the extra territory accidentally assigned to them.

And Garfield believes the commercial and political significance of reliable maps can only grow. "Not only will it become the decisive element in the smartphones and apps we buy, it is also the way that shops will find out when we are nearby," he said.

A revived interest in representations of planet Earth is also reflected in Jerry Brotton's book, A History of the World in Twelve Maps, out last month, and in an exhibition of globes at the Royal Geographic Society in London next month.

"The amount of interest in maps and globes at the moment has probably got something to do with the fact that we are all able to find ourselves on maps now at the touch of a screen," said Garfield. Throughout history, he points out, the centre of a map of the world has been the place to be, and today individuals find themselves at the centre courtesy of their smartphones.

"It used to be Jerusalem that was placed at the centre of Christian maps," said Garfield. "Or in China, it would have been a place called Youzhou. Now for the first time we are all at the centre."

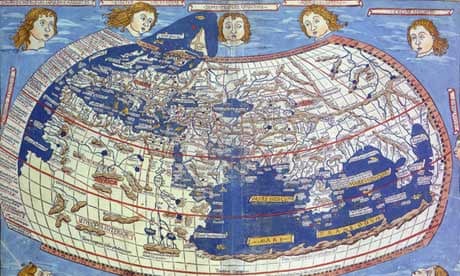

Histories of cartography often start in AD150 when Claudius Ptolemy, the first "geographer" to use the term, wrote a book about the skill of map-making. He laid out rules about the geometric lines of latitude and longitude and gave co-ordinates for more than 8,000 locations in the ancient world. But Garfield believes it is possible to look back further, to the moment when the human mind began to develop.

"In Unweaving the Rainbow, Richard Dawkins suggests that map-making is one of the basic things that first distinguished us from animals. We needed to explain to each other where to hunt, so spatial awareness, plus the skills of representation and communication, had to develop."

In his book about maps, Brotton, a professor of renaissance studies at Queen Mary, University of London, examines the difficulties faced by map-makers through the stories of 12 key maps, going from Ptolemy's ground rules right up to Google Earth, and taking in influential Islamic and East Asian works.

He concludes that maps rarely come without an agenda. "The idea of the world may be common to all societies, but different societies have very distinct ideas of the world and how it should be represented," he writes. Garfield sees the history of cartography as a way to understand political influence too. "It is always about the proprietorial impulse," he said. "A map says not only 'We know all this', but often 'We own all this' too."

This is clear when shipping routes, the paths to gold and spices, are first traced, and even with British Ordnance Survey maps, which Garfield believes conveyed a sense of power and territory.

The appeal of maps can also be purely visual. "I am a sucker for all kinds of maps and it seems that lots of people are," said Garfield. "For many, the best ever is the 17th century Atlas Maior made by Joan Blaeu. It is just an absolutely wonderful thing – the coffee-table book of its day, complete with wonderfully strange creatures in the sea."

A fresh interest in hand-drawn and personalised maps is providing some antidote to the advance of digital technology, Garfield thinks. The work of artist Grayson Perry, who maps out British social mores with his wall tapestries, is an example. Garfield also notes the enduring appeal of maps in children's literature, from Treasure Island to The Chronicles of Narnia and The Hobbit. JK Rowling's Marauder's Map in the Harry Potter books is a recent example. "Vladimir Nabokov also did a wonderful map of the characters in Ulysses and of where they all go in one day," said Garfield.

Peter Bellerby, a professional globemaker, fell under the spell of cartography five years ago when he tried to make a globe for his father's birthday and he has not stopped since. "I had to figure out the very basics of globemaking," he has explained. "How to make perfectly spherical balls for instance." A selection of his work will be displayed at the Royal Geographical Society next month.

Garfield owns two globes. "There are things you can only get from a globe," he said. "There used to be one in every Victorian classroom and, even if it wasn't consulted, it was a symbol of power."

As the battle for pre-eminence in smartphone maps escalates, there will be slip-ups and deliberate misrepresentations on the way, he says. There always have been: for two centuries the state of California was shown as an island. And for a century the mountains of Kong stretched across Africa, until a French explorer found they were not there, while names are a political minefield.

"We have places that are named that are claimed to be owned by three different countries," Google's McClendon told Garfield. "And they have two or three names associated with them."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion