Story highlights

Singapore is using crowdsourcing to compile its recent history

The city-state will celebrate 50 years of independence in 2015

It's calling on all citizens to upload memories to its Memory Project

Singaporeans have shared memories in photos, blog posts, e-books and videos

Dr. George Khoo vividly remembers the opium dens.

Fifty years ago, they lined the street just down from his small Singapore clinic. It was the time just before independence in 1965, before the shiny skyscrapers, velvet freeways and almost-painfully spotless streets.

Many of his patients were addicts struggling to unhook, he writes. Many would not come to the clinic. He had to go into the dens to find and treat them.

“It was hard treating them in the pitch darkness,” he recalled. “I had to call out their names and they would call out to me. I would then give the injection, but I never really knew for sure who exactly I was treating.”

Khoo’s gritty memories have been captured as part of a unique, crowdsourced history project that Singapore has commissioned ahead of its 50th anniversary of independence in 2015.

The goal of the Singapore Memory Project is not to produce a slick history.

“We’re not going for certain types of people,” said Memory Project director Gene Tan. “What we’re looking for is specificity. It’s the messiness of it, of the lives people lived and the communities they lived in, that we want to have.”

So far, Singaporeans have sent in more than 400,000 memories – including text, audio, still images, even e-books and video uploaded to the project’s website or through a free iPhone app available on iTunes. With the support of 120 partner groups and 130 volunteers, the project hopes to record 5 million Singaporeans, virtually everyone in the country.

Before the economic boom

Along Singapore’s shoreline in the years after independence, fishermen would lay their morning catch on the beach where vendors from the nearby “hawker” stands would buy fish to serve at their small, hot food shacks, recalled Faridah Anom.

Today, that site is home to a row of terrace houses.

“Everything is gone,” Anom said. “It was so long ago.”

It was only the 1960s, the 1970s. But in Singapore, that was another eon.

In 1965, the year of independence, Singapore’s per capita GDP was $516. Last year, it was about $60,000 – among the top five in the world.

That mammoth growth has dramatically transformed Singapore’s landscape in just a few short decades, from rows of hardscrabble fishing shacks and bungalow neighborhoods to a towering glass, steel and concrete wonderland of efficiency, wealth and dazzle.

Little remains of what was there just a short time ago: Many of the houses, the stores, the neighborhoods and the communities have been transformed.

Hamzah Yaacor, 17, only remembers today’s booming Singapore. As a volunteer for the Singapore Memory Project, Yaacor and two other students are interviewing seniors along a just a few streets for a small book of interviews titled “Streets We Remember.”

Yaacor said he is learning more than he ever did in school about Singapore’s history from people like Anom.

“You start talking about their memories, and they just open up,” Yaacor said. “Looking at this personal history, it’s more authentic.”

Singapore schools, he said, teach history as a blanket of facts, figures, dates and places. But he said it’s actually more like a patchwork quilt, something that he and his fellow students hope to capture for the Memory Project.

All the memories collected have fallen into two broad categories: individual recollections about Singaporeans’ communities, their friends, their schools, the way they were. The other are collective memories – the experiences and objects that nearly everyone shared.

Big and small memories

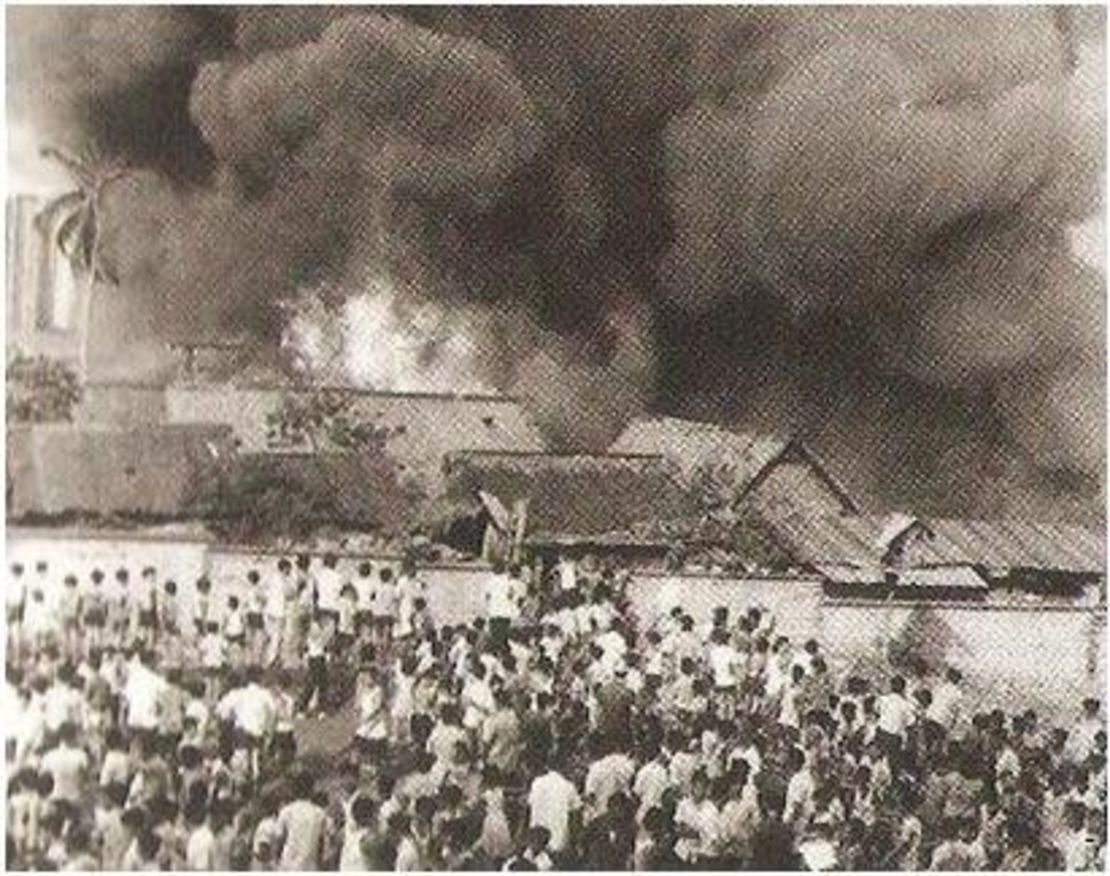

James Seah was 11 years old in 1961 when a massive fire tore through his neighborhood, Singapore’s Bukit Ho Swee squatter settlement, destroying some 2,000 homes.

“Dark billowing smoke filled the sky, the smell was toxic,” Seah recalled in his Singapore Memory Project blog post. “People were screaming and shouting ‘Fire, Fire’ … I had never seen a big fire that burnt down houses and places before. I had not read about it, or watched it on television (monochrome TV broadcast in Singapore only began in April 1963) or at the movies.

He described a feeling of “excitement rather than a fear of danger.”

“My mother and I ran as fast as we could as we fled from the burning houses,” Seah said. “There was a stampede. The older and weaker people were carried by younger and stronger ones.”

The Bukit Ho Swee fire left four dead and thousands homeless and is one of those moments in Singapore’s history where most people alive at the time remember where they were when they learned about the massive blaze.

Other memories focus more on Singapore’s rapidly evolving culture, including one e-book focusing on the traditional games children played, arranged by clicking on alphabet letters made to look like children’s blocks. Another e-book covers the playgrounds that have been swept away by the city-state’s rapid development.

Ruth Ann Keh, 17, and two of her fellow students compiled the memories of people living in the Rochor Centre complex that is slated to be torn down in 2016 to make way for a new expressway. Many residents have lived there for decades, and neighbors were like family. One resident told Keh the story of a birthday party some boys held years ago on an open deck, and how all the neighbors came down.

“What struck me the most was the sense of family,” Keh said. “All the people I talked to mentioned the bond. Now, you don’t know your neighbors. It’s not as it was before. But it is possible to have a sense of neighborhood. It’s just a matter of making time.”

Sharon Ng recalled fond memories of growing up watching her grandmother use a bucket instead of a cash register at the Kian Guan sauce factory.

“Inside, my father, uncle and one hired worker would sit on small stools or on the floor, hard at work six days weekly making chilli, tomato and soya sauces, bottling them and tying the bottles expertly with thin rope-like twine in packs of six or 12,” Ng wrote in her Singapore Memory Project post. “Grandma sold sauces at the ground floor shop while the rest were sold to other businesses. All her takings were kept in an iron pail on a pulley. She just pulled the rope down, put in the money and the pail went up.”

A generation’s gift

Singapore’s Memory Project is about a country getting personal with itself, and project director Tan said most of the posts are “very emotional.”

“There’s a lot of longing in all the memories – longing and attachment to people who are gone, places that are gone,” he said.

But he said there’s also celebration about the stability that Singapore enjoys today.

“There’s a great sense of relief of where we are today,” Tan said.

In the process, the Memory Project staffers say, they are learning things about themselves that they never expected. They thought the project was about talking to others, about something external. But they’ve realized that documenting Singapore’s history is about them, too.

“We started out with a lot of arrogance,” Tan explained. “We started with an intent to hack into other people’s memories. What’s humbling is there’s nothing to hack into, but only things to discover.”

Singapore is a young country that has packed more history into its few years than most others. But in a place where most everyone came from somewhere else, the Memory Project is helping define what it means to be Singaporean.

It is bringing texture to the life of the nation, endowing a diverse people with a common identity, a way to look forward together. The submissions also make for astonishingly interesting reads.

“This is the gift of our generation,” Tan said. “History is not just for the leaders. It’s about random people, too.”