Watch Tuesday’s presidential debate and CNN’s exclusive expert analysis starting at 7 p.m. ET on CNN TV, CNN.com and CNN’s mobile apps for iPhone, iPad and Android. Web users can become video editors with a new clip-and-share feature that allows them to share favorite debate moments on Facebook and Twitter. Visit the CNN debates page for comprehensive coverage.

Story highlights

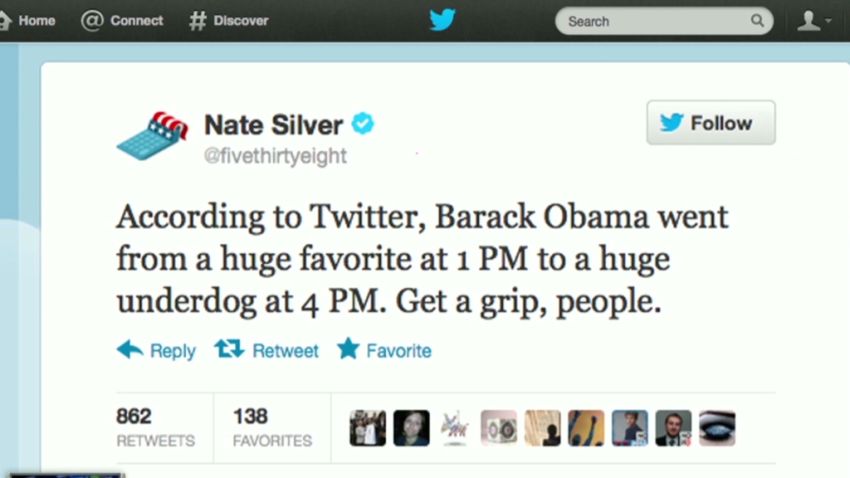

Some people jump to conclusions based on polls, putting uncertainty aside

We're uncomfortable with uncertainty -- hence the market for predictions

FiveThirtyEight.com's Nate Silver: A "dose of humility" necessary

When predictions go wrong, some people deny the result

These are the days of uncertainty. The pollsters tell us so.

You wouldn’t know it from the pundits, however. They rend their garments or sing hosannas as if each little survey statistic was handed down from on high, chiseled into tablets.

“Is Mitt Romney panicking?” asked a Washington Post headline in mid-September after polls indicated President Obama had received a post-convention bounce. “Did Obama just throw the entire election away?” an alarmed Andrew Sullivan asked after the first presidential debate, reeling off a flurry of the president’s poor polling numbers.

The fact is, every day is a day of uncertainty – and we hate that.

Psychologically, it gives us comfort to determine our fates, says Dr. David Reiss, a San Diego-based psychiatrist and expert on personality dynamics.

“We’re sort of hardwired to predict what is going to happen to protect ourselves,” he says. After all, for much of mankind’s recorded history, a prediction could literally mean the difference between life and death – whether it was determining a village’s vulnerability to attack or attempting to figure out the size of the coming harvest.

But, he adds, there’s also a sense of power and ego in knowing the future: “If I can predict things, I have some control and it releases feelings of helplessness or fear,” he says. “The more I can predict, the smarter I am and the better I look to others.”

Throw in the chattering, nattering, opinion-splattering classes – which traffic in confidence and authority – and you create a stew of statements that seldom veers from bet-the-house conviction.

In his new book, “The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail – But Some Don’t,” statistician and FiveThirtyEight.com creator Nate Silver looked into almost 1,000 predictions of the D.C.-based “McLaughlin Group” pundits. They were about half right – no better than a coin flip. These Beltway insiders “displayed about as much political acumen as a barbershop quartet,” Silver writes.

Compare that with weather forecasters, Silver says in an interview. The profession, which has improved consistently over the years, makes a virtue out of unknowns, such as the “cone of probability” in hurricane tracking. “They’re being honest about how much they know and how much they don’t know,” he says.

“So they’ve made progress, whereas people who are trying to make the perfect prediction and take political science and treat it as though it’s physics are failing much more often,” he says. An appreciation of uncertainty “requires a dose of humility that the weather forecasters have that the (pundits) don’t.”

Numbers overload: Polling data hype sways voters

‘You find the uncertainty and kind of wallow in it’

We may want to laugh about the “McLaughlin” folks – they’re providing entertainment, not prophecy – but the overall point of Silver’s book is that poor predictions can cost society dearly. Look at the financial crisis, which blindsided most economists, or the early visions of the Iraq war, which turned out to be anything but the predicted “cakewalk.”

It’s no wonder that, throughout history, kings and emperors put so much stock in soothsayers, or that tales of Joseph, Daniel, Cassandra and the Oracle at Delphi are still touchstones.

We also revel when the experts are wrong. An Irish mathematician said speedy trains were impractical because they’d cause breathing deprivation. A 1901 critic said only one of Mark Twain’s works would endure: “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.” And then there’s the founder of the onetime technology behemoth Digital Equipment Corp., who said in 1977, “There’s no reason a person would want a computer in their home.” Digital was bought by home computer-maker Compaq in 1998. (TheWeek.com has a whole page devoted to such opinions.)

Pollsters shouldn’t get cocky, either. In 1936, the prestigious Literary Digest – which ran what was then considered the gold standard of presidential polls – proclaimed that Republican Alf Landon would beat President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Instead, Roosevelt won the greatest electoral landslide of modern times. The Digest, suddenly a laughingstock, folded two years later.

The Digest’s failure led to the rise of pollster George Gallup, who brought statistical rigor to polling. But even Gallup could falter: His poll missed the Harry Truman-Thomas Dewey contest of 1948.

Futurists are professional predictors, some of them paid tidy sums for their expertise in forecasting the direction society, technology and nations are moving. Cindy Frewen Wuellner, an architect and chairwoman of the Association of Professional Futurists, says the key to good forecasting is knowing what you don’t know and doing your research.

“As a futurist, you find the uncertainty and kind of wallow in it,” she says. “You make sure the uncertainty is explored layer by layer.”

She observes that context is key. We’re always making fun of the fact that we don’t have a “Jetsons”-like present of flying cars, she points out, but seldom think about what’s required to build that kind of society. “It’s not the innovation, it’s the diffusion of it,” she says, pointing out that we’d need to create a whole infrastructure for such vehicles (which do exist). “It’s enough to have the FAA dealing with all the planes in the air. What if every single car was a plane?”

People (like, perhaps, sports talking heads or Washington pundits) often believe predictions are “a single scenario,” she adds. “Futurists believe in futures with an ‘S,’ meaning multiple scenarios. And the only scenario that isn’t going to happen is business as usual. You can’t just take today and multiply it out and call it tomorrow.”

Which is one of the issues in interpreting polls. Too often, observers look at what is so often characterized as a “snapshot” of data and jump to conclusions. It doesn’t help, says Emory University political scientist and polling expert Alan Abramowitz, that there are more polls than ever.

“If you go back to the 1950s and ’60s, there were only a few polling organizations,” he says. “It’s really in the last two or three presidential election cycles that we’ve seen a proliferation of polls.”

Moreover, as technology has changed, so have polling methods. Polling used to be done face to face. Now it’s all done by telephone – a much cheaper alternative, Abramowitz says, but not necessarily more accurate, what with robocalls, lack of callbacks and sampling challenges based on land line and cell phone users. Then there’s “rational ignorance” – the consciously shallow understanding and apathy of many possible respondents. There have been movements to counter these flaws, such as Stanford University’s “Deliberative Polling,” but the general process remains imperfect.

Some organizations have adjusted well, others have not – but all the data are thrown into the mix, a haystack of straws for pundits to grasp.

‘Town meeting’ or fodder for denialists?

In his book “When the People Speak,” James Fishkin, a Stanford political scientist, observed that George Gallup believed polling solved a host of civic ills. Along with mass media, polling “created a town meeting on a national scale,” Gallup wrote in 1938.

So much for that. Instead, many people have used the snapshot statistics as a club with which to pound their opponents – or they deny their usefulness entirely.

Indeed, these days, some people hold onto their views so strongly that they resist actual facts. Both parties have fallen into the trap: In 2004, some Democrats, lulled by early exit polls that indicated a narrow victory for John Kerry, claimed that the election had been stolen. More recently, some Republicans have claimed that the polls themselves are skewed.

In an essay for Slate, law professor Richard L. Hasen, author of “The Voting Wars,” asked if Republicans would accept an Obama victory. He pointed to a rise in distrust of election results – from members of both parties – since the 2000 Bush v. Gore contest.

“The lesson from these statistics is simple. If my guy won, the election was fair and square. If your guy won, there must have been some kind of chicanery,” he writes.

Sigh.

Sometimes, says futurist Frewen Wuellner, you just have to accept that you don’t know the future until it occurs. In the meantime, research, prepare – and expect uncertainty.

“Anybody who says they know for sure – they’re lying,” she says. “They don’t know. Nobody knows for sure. There’s always something that can happen.

“It’s what makes the prediction business so big.”