The metaphoric relationship between dancing and sex is a two-way street, as in "rockin' and rollin'" and the euphemistic "horizontal tango", a term so cheesy it should turn all right-minded people into wallflowers. Latin dancing, in particular, we think of as a public analogue of intercourse. Inevitably The Simpsons has spoofed this idea with a dance called La Penetrada, which promises to make "sex look like church". In literary circles, Eros graces Jane Austen's dances, despite all the juvenile giggling over red breeches and the stubbornness of the leading man. One of the central cinematic examples of dance as erotic affirmation surely belongs to Saturday Night Fever, with John Travolta's exuberant pelvis nodding "Yes, yes, yes!" to all of life's propositions.

But dancing, especially when conducted with precision in dimly lit ballrooms, also has a ghoulish aspect, one that our innate cultural sensors immediately recognise. In fact, if people still dressed as skeletons for Halloween, rather than as someone from a viral internet video or a coquette with a smear of fake blood on her lips, then the parties thrown on 31 October would be less rock'n'roll and more evocative of that old medieval archetype, the danse macabre. This 15th-century scene was typically set in a graveyard and showed the personified figure of Death leading a troupe of the living intermingled with cavorting skeletons. It has since influenced all the major art forms, and from mid-November, London's Wellcome Collection will host an ensemble of pictorial danses macabres as part of its major winter exhibition, Death. The collection is the work of the Chicago-based former antique print dealer Richard Harris, and among this 300-piece tribute to mortality there is a sort of international championship of skeleton-weight dancing.

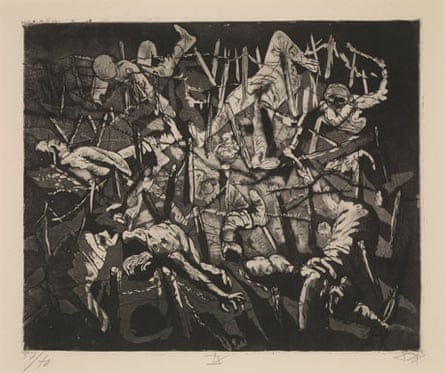

Emphasising the carefree spirit of the world beyond, the 19th-century Japanese artist Kawanabe Kyosai's Frolicking Skeletons shows a bony whorl of carcasses on a hillside. Walter Sauer's 1925 interpretation, a black-and-white woodblock print, is a more obvious cousin to our contemporary iconography of bats, tombstones, full moon and skulls, and was inspired by both European symbolism and Japanese printmaking. Otto Dix's Dance of Death 1917 is a sarcastic title for his battlefield etching of dismembered soldiers skewered on barbed wire, for there's no music in these splayed corpses. The soldiers are as evocative of a jig as a chalk outline is of a break-dancer. Tellingly absent in Dix's scene is the animating figure of Death. If war's monstrosities make collateral damage of God, then it seems that the Reaper, too, has no place in this evil world of men.

Traditionally the allegorical agenda of the danse macabre is to remind the vainglorious that all of life's roads, from the gold-paved to the potholed, lead to the final, spasmodic chorea of the deathbed. And yet dancing is a complex image through which to illustrate death's egalitarianism, since few places have traditionally shown less sympathy to democracy than the European ballroom. Courtly dances have always been animated by the violence of hierarchy. Silk fans open and close like barber knives, and even the slang of the dance is serrated: when nobles aren't cutting each other with their glances, they're carving happy couples apart by cutting in. It's therefore apposite that later versions of the danse macabre exchanged the graveyard for the aristocrat's party in order to emphasise the immoral decadence of the privileged classes. As an uninvited challenger to this opulence, Death hits the dancefloor bearing the largest and heftiest of the metaphorical blades.

In Edgar Allan Poe's story "The Masque of the Red Death", Prince Prospero holds a grand party in his mansion while around him his serfs are dying of plague. Prospero arrogantly believes that wealth ensures immunity from contagion, until the masked presence of Death gatecrashes the soirée and "with a slow and solemn movement, as if more fully to sustain its role, stalked to and fro among the waltzers". A visual equivalent to Poe's eerie massacre is Alfred Rethel's Death the Strangler – The First Outbreak of Cholera at a Masked Ball in Paris, 1831, which is also part of the Wellcome exhibition. In this wood engraving, Death is the sauciest allegory on the block, manifesting as a skeleton among the fresh corpses of partygoers, wearing something between a monk's hooded habit and a negligee. Jauntily playing the fiddle with a thigh bone, one severely well-turned ankle thrust forward, Death takes over from the band of musicians who are depicted fleeing in horror. Here Death targets the upper classes, and, as in Poe's tale, the music's tempo seems to catalyse the infection, making it an instant killer.

The great literary modernists used the danse macabre more subtly, rarefying it into a sort of dreadful fume, a felt but unspoken atmosphere that gave pallid overtones to otherwise convivial scenes. Modernism was in many ways a morbid enterprise, with keen instincts for investing the festive with the funereal. The relatively new invention of the X-ray – science's realisation of memento mori – offered a cutting-edge metaphor through which to explore our mortal fears. There's no shortage of sinister balls in Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time, and at one of them an X-ray image becomes a party-piece, eliciting one man's grave denial "at the sight of this rosary of bones labelled as being a picture of himself". Arguably this heightened awareness of what lies beneath prompts another of Proust's characters to compare an elderly guest to "a skeleton in an open dress".

Proust diffuses the heavy-handed allegorising of Poe and Rethel by working with the same ideas at the level of metaphor. His most chilling partygoer is a doctor by the name of Professor E, described as wandering around the gathering alone, "like a minister of death". But Proust also understood aristocratic vanity, and how the complex rituals of French social life were designed to suppress the possibility of death, just as Prince Prospero believes his palace gates will keep out the plague. In one of Proust's darkest and funniest party scenes, the dying Charles Swann tries to broach the subject of his impending demise with his hosts, the Duke and Duchess of Guermantes. Swann accepts their wilful evasion of his announcement, knowing "that for other people their own social obligations took precedence over the death of a friend". While his wife disappears to change her shoes, the Duke talks helplessly to Swann in morbid colloquialisms, displaying a Freudian compulsion that would make Basil Fawlty cringe. He tells poor Swann how his wife is "tired out already, she'll reach the dinner-table quite dead. Besides, I tell you frankly, I'm dying of hunger."

Virginia Woolf, an admiring reader of Proust, was interested in the dramatic potential of the party as a way of bringing to the fore that which the joviality of the occasion attempts to deny. In Mrs Dalloway's climactic gathering she describes one guest as a "spectral grenadier, draped in black". Death arrives here, too, not as a shrouded figure but in the form of gossip: a shell-shocked soldier, a patient of one of her affluent acquaintances, has that very evening flung himself from his window. "Oh! thought Clarissa, in the middle of my party, here's death." The soldier's suicide is a textbook memento mori for Mrs Dalloway, who has been rendered blasé to the terror and beauty of living by the self-absorbed anxieties of social life. One of the cruellest moments in Stephen Daldry's film The Hours, based on Michael Cunningham's Woolf-inspired novel of the same name, occurs when a terminally ill character tells his friend and carer: "Oh Mrs Dalloway, always giving parties to cover the silence."

The Christmas party in James Joyce's "The Dead" is another attempt at the suppression of existential silence, and is perhaps the most concerted modernist interpretation of the danse macabre. The floors of the house creak and thump with waltzes and quadrilles, but this liveliness summons ghosts. Gabriel Conroy's wife Gretta stands on the stairs, transfixed by a song that reminds her of a dead love from her youth. After Gretta tells Gabriel about this memory, Gabriel becomes conscious of the decay he has felt all along. In his nervous speech at the party he describes his old aunt as being "gifted with perennial youth". However, once cuckolded by his wife's reminiscences, he thinks how this same aunt "would soon be a shade … He had caught that haggard look upon her face for a moment when she was singing."

On a wall above the piano, Gabriel notices a picture of Romeo and Juliet's balcony scene hanging beside a needlework depiction of Edward IV's sons, presumed murdered in the Tower of London. Desire and death rub shoulders here, by now a familiar partnership in our post-Freud world. Richard Harris's collection reflects the dynamic between eroticism and annihilation in pieces such as Ivo Saliger's The Doctor, the Girl, and Death. In this muted etching on brown paper, a brawny doctor holds up a slumping, naked girl, his free hand jealously pushing against the skull of the crouching skeleton that grasps the girl's thighs and paws at her hair. A piece entitled "Au Revoir" is a French postcard displaying a black-and-white sketch of two lovers on the cusp of a kiss, their dark bouffant heads of hair doubling as the cavernous eyes of the skull into which their clinch is set. A photograph by the Czech photographer František Drtikol, who often used professional dancers as his subjects, shows a female nude holding a skull. The erotic vitality of the model's strong, naked physique contrasts with her sobering prop, but the meaning of the image is made ambiguous by the careful balance of its symbolism: does the dwarfed skull's empty gaze wither the nude's fecundity, or do life's largeness and vigour ultimately overwhelm the smallness of death?

The Freudian notion that pleasure and destruction are our two principal motivations continues to fuel the potency of dancing as an ambiguous symbol long after its macabre medieval career. After the modernists, Eros and Death continue their waltz in Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa's The Leopard, a novel that is clearly alert to the decay woven into youthful romance. At yet another deathly ball, men wearing black are likened to carrion crows; the women are wrapped in dresses from Naples, sent to them "in long black cases like coffins". The party's beautiful young couple, Tancredi and Angelica, remind the Sicilian prince, Don Fabrizio, of actors playing Romeo and Juliet (them again) who are unaware of where the script will lead them. Melancholy with middle age, the prince watches them blithely sailing over the dance floor, sensing both their tenderness and self-interest, and how these complexities of love are in the end trumped by the unspoken fear of death, "by the mutual clasp of those bodies destined to die". Here Don Fabrizio is sick with the nostalgia portrayed in Alexander Pope's "Epistle to a Lady", which dramatises lost beauty as a sort of hag's jig: "Still round and round the Ghosts of Beauty glide, / And haunt the places where their Honour dy'd."

There is ironic power in coupling the vivacity of dance with the tomb's stillness. At their best, the artistic progeny of the danse macabre occupy that affecting region between archetype and cliché, allowing the artist access to themes of hubris, decadence, ephemerality and sorrow. Dance being a temporal medium gives it a natural kinship with the idea of mortality. In Joyce's story, Miss Daly's waltz "made lovely time" but, while time may be many things, lovely isn't one of them. The waltz's three-quarter pulse produces a temporal circularity that attempts to defy life's linear diminishing.

Dance's temporal evasions and manipulations serve only to make the ineluctability of time more apparent, and it's arguably this curious inversion that has attracted the artistic imagination. It is harder to sense the frantic denial beating within free-style dancing's sheer exhilaration. But even young, rhythmic Tony in Saturday Night Fever feels the acceleration of all this exhilaration, as though disco, being life in fast-forward, is its own groovy kind of memento mori. "Dancing can't last for ever," Tony says. "It's a short-lived kind of thing … I'm getting older, you know?"

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion