There is a saying in Guinea that is popular among those who work in development: "Everything is a priority". It is a wry observation that, in a country in which almost nothing works, it is difficult to work out what to tackle first.

The facts are stark. A recent survey showed that 62% of Guineans have no access to running water, 62% have no access to electricity, 65% say they have inadequate access to roads, and 72% think the justice system is broken. The country's human development indicators are well below those of other sub-Saharan African countries – the UN ranks the country's development 178th of 185 in the world.

As a result, Guinea's first democratically elected government since independence – led by Alpha Condé, a former doctor of law and professor at the Paris-Sorbonne University in France – is trying to reform and rebrand the country after decades of chronic mismanagement.

Former World Bank economist and minister of finance in Guinea, Kerfalla Yansané, says: "We want to attract not only donor money but to interact with the private sector, and we are working hard at this." "We are trying to reach out to all partners, to ensure that we can be in a position to send our message across."

Condé, Yansané and other government figures convened investors at a hotel in London last month to promote the merits of doing business in the west African country.

At the heart of efforts to attract investors are reforms to the mining code, and the creation of a committee to re-evaluate all 18 mining contracts and make recommendations for some to be renegotiated. "We are making an in-depth assessment of the contracts. If there are some imbalances, our mandate is to negotiate with the mining companies in order to regulate them," says Nava Touré, president of the committee.

But the review has come under criticism from all sides. Mining companies – many of which are watching the criminal investigation of BSG Resources (BSGR), which is accused of using bribery to obtain concessions – are nervous about the prospect of scrutiny and dubious about being asked to renegotiate legally binding contracts.

Anti-corruption activists say the process lacks teeth and depends on the goodwill of companies to renegotiate the terms of mining deals, something the government admits.

"It's true that it will be through persuasion we are going to work, and through evidence," says Yansané. "We expect these companies to be concerned about the image, their credibility. They should sit down around the table and discuss with us."

Olivier Manlan, principal economist for Guinea at the African Development Bank, which is supporting the review process, says: "The process is more symbolic than anything else. It is really about setting the tone for the future governance of Guinea. But it is important that these messages are sent now, so that any future government can build on them."

Guinea is not short of anti-corruption bodies. In addition to the mining review committee, the country has an anti-corruption agency (ANLC), audit committee, and an inspectorate division of the finance ministry, applauded this year for uncovering corrupt practices among its staff.

But corruption remains a formidable problem. A recent survey found that 98% of businesses in Guinea, and 93% of citizens, experienced corruption, with 86% of businesses and 79% of citizens saying the issue had got worse. "Our analysis of corruption over the past three years is that it is present in all sectors in Guinea," the report says.

Some question whether anti-corruption bodies have the power to make a difference. Abdoul Rahamane Diallo, Guinea programme co-ordinator for the Open Society Initiative for West Africa, says: "The problem with all these bodies is that they do investigations, they get reports, but they cannot prosecute.

"They refer their files to the government, who sit on them. Some of the people in the current government were also in the past government, and if they are implicated, then they are not going to act. These bodies have no real authority, their funding is a problem. If you visit their offices, you can see that they are yet to function properly in terms of mobility, office supplies, salaries."

At the anti-corruption watchdog, perhaps fittingly located at Guinea's "kilometre zero" – the point from which all distances are measured – the director, François Falcone, admits a struggle to balance attracting foreign investment and protecting national interests. "The rules are very weak for multinationals. If you try to bring them to account, they can hire 50 lawyers to defend themselves. It's difficult for a country like ours to compete with that," he says.

"Sometimes it feels as if the state is disappearing beneath these private enterprises," adds Falcone, whose organisation has 44 staff and a budget of only £75,000 a year. "These companies have the means to influence our politicians and political parties. But fortunately we are beginning to form stronger institutions to take them on."

Guinea's government says it has demonstrated its commitment to tackling corruption, by taking on BSGR and by investigating its own staff. Last year, several central bank employees were convicted of embezzling state funds using fake documents.

"This is evidence that we can't sit down and ignore corruption within," says Yansané. But in response to allegations that only the most junior civil servants involved had been prosecuted, the minister admitted that until the judiciary was strengthened, accountability would remain imperfect.

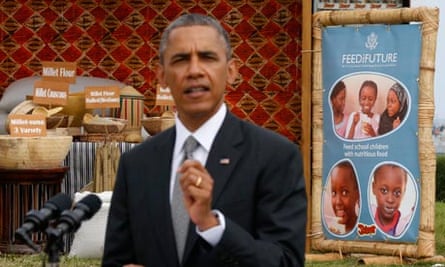

Guineans say they were the only neighbouring country whose supreme court judges were not invited to Dakar to meet Barack Obama on his Senegal tour last month, which has been interpreted as a damning but not unfair indictment on the state of the judiciary.

"We have to keep addressing the weaknesses of all our institutions, particularly in the judiciary," says Yansané. "If there is no judiciary, there is no security for contracts, and if there is no security, there will be no investment."

One western diplomat, who spoke on condition of anonymity, agreed: "We are starting from an extremely low base. It will take decades for Guinea to transform itself the way that some other countries in the region have. But it has made a start."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion