Story highlights

China has 55 official minorities but preserving language and culture is difficult

Education system prioritizes national language Putonghua

China likes appearance of ethnic diversity, but wider trend is of gradual assimilation

Tourism a mixed blessing; some villages like "human zoos"

Shi Wenchang has been an elementary school teacher in this remote rural village for 39 years but he doesn’t teach his mother tongue, even though it’s used by almost three million people.

His job is to get the village, home to members of the Dong ethnic group, chattering in Putonghua, also known as Mandarin – China’s national language – although he can switch into the local language – Dongyu – in the early years to bridge any gaps.

“When they start learning to write, they start learning the Han language,” he says, referring to China’s largest ethnic group, which makes up 90% of the population and is politically and culturally dominant.

Teacher Shi thinks it’s important they master Putonghua, which will enable them to seek work beyond the confines of their isolated village, but fears his language is disappearing.

“If we don’t have our own language, there are many things, many stories from the past that we won’t have and that will be a big loss.”

READ: China’s migrant workers seek a life back home

The threat is not just the result of an education system that prioritizes the official national language.

As China’s economy has boomed in recent years, many have left their villages to work in coastal factory towns and returned more at ease conversing in Putonghua than their native tongue.

Some slip into Chinese for even the closest family relationships, calling their mother and father mama and baba.

“Before we’d never use these words,” he says. “In our Dong language it’s bu (father) and nei (mother).”

China is home to 55 ethnic minorities, but only two – Tibetans and Uighurs in China’s far West – get much international attention, usually because of discord with their Han Chinese rulers and neighbors.

The others are dotted around the country, with most, like the Dong, clustered in the poorer mountainous regions of southwest China.

Ostensibly, there is little overt friction with the Chinese majority although Shi says when he was younger, he was afraid if Han people came to the village.

As minorities, they are not subject to the strictures of China’s one-child policy but carving out a distinct cultural identity is difficult.

China is happy to have the appearance of ethnic diversity, but the wider trend is of gradual assimilation, says June Teufel Dreyer, a professor at the University of Miami.

“It’s a wrecking of their culture under the guise of preserving it,” she says. “People complain that their folk tales are rewritten to fit Communist ideals.”

READ: Chinese village braces for change

The Dong’s cultural heritage is also weakening as a younger generation adapts to more modern ways.

The ethnic group has a strong musical tradition and when Teacher Shi was a teenager, songs were used for courtship.

Accompanied by a gang of friends, he stood outside the house of his now wife and declared his love for her in song.

“The girl keeps the door shut and you have to keep singing until they open it and let you in,” he says, before plucking a stringed instrument off the wall of his living room to demonstrate he still has the knack.

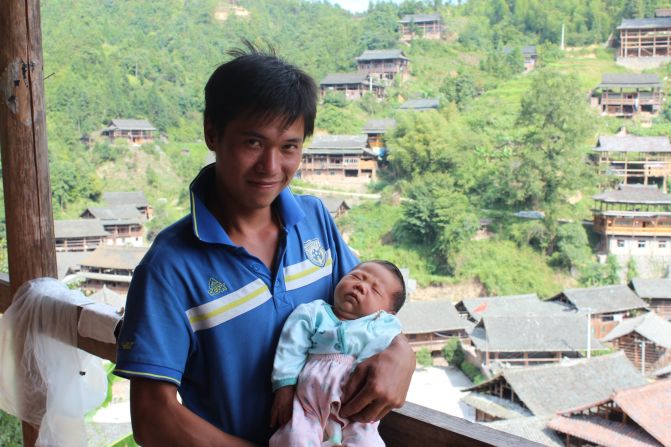

However, things have changed since his youth. Shi Tao, a 25-year-old factory worker back in the village for the birth of his son, laughs when asked if this was how he met his wife. “Our grandparents did this, we do not,” he says.

Teacher Shi hopes that tourism may reinvigorate the Dong’s unique culture and encourage younger people like Shi to stay closer to home and engage in traditional pursuits.

The village, a picturesque cluster of timber houses surrounded by bamboo groves, has been designated a heritage site and earmarked for tourism development.

“The tourists will come here to see our people’s traditions and culture. If more people come then maybe the preservation of our traditions will be stronger,” says Teacher Shi.

Elsewhere though, tourism has proved, at best, to be a mixed blessing. In villages already on the tourist trail, minority culture is a commodity to sell to passing crowds.

“Some villages become human zoos,” says Dreyer. “Some are happy about what they get out of it but others resent it.”

This spectacle is on display in nearby Xijiang, home to the Miao ethnic group, where villagers perform a live show every afternoon in a specially created outdoor amphitheater.

It’s standing room only and the audience laps it up. But, with girls performing in mini skirts and skits lampooning the group’s predilection for drinking potent rice wine, it makes some older residents shudder.

“These performances aren’t real Miao culture,” says Tang Cheng, the village chief. “People just want the entertainment factor.”

The hope is Dali will escape the rampant commercialization that has engulfed some minority villages – its development is being overseen by the provincial bureau of cultural heritage with help from a U.S. NGO, the Global Heritage Fund.

Both organizations want to preserve the village’s cultural DNA and hope it can become a UNESCO world heritage site.

Still, the lives of Teacher Shi’s three children, who all work outside their village, demonstrate that the chances of a cultural revival for the Dong are slim.

In their 20s and 30s, one is an accountant in Wuhan, a large city in central China. The other two are teachers in the same province. They only wear traditional clothes when they come home.

Shi has no grandchildren yet but is sanguine about the chances of his descendants speaking his native tongue.

“If they are always living outside the village, then they will definitely speak Putonghua, ” he says.