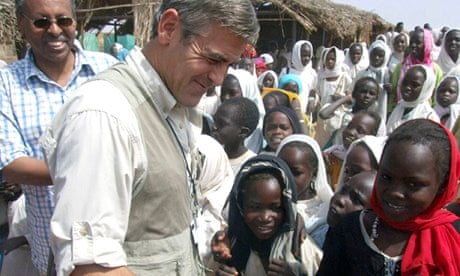

When violence erupted two weeks ago in the world's youngest country, one of the first voices to speak out, before the US president or the head of the United Nations, was that of the Hollywood actor George Clooney. There was nothing particularly objectionable about his counsel, which in any case was more likely authored by the American activist John Prendergast, with whom he shared a byline. It spoke of the need for a robust UN response and, even as tens of thousands of civilians fled ethnically motivated death squads, of the "opportunities" present in South Sudan.

This is a country, not yet two and a half years old, whose birth has been soaked in celebrity like no other. As well as Clooney, Matt Dillon and Don Cheadle have been occasional visitors who have tried to use their star power to place the international public firmly in the corner of this plucky upstart nation.

Unsurprisingly, the actors were highly effective at communicating a narrative about the new country that borrowed from a simple script. The south had fought a bloody two-decade battle for its independence against an Islamic and chauvinist north led by an indicted war criminal. The cost of that war, regularly touted as two million lives, meant that the south would need huge development support to lift it from the impoverished floor of every quality of life index published.

The great threat in this narrative was the vile regime in Khartoum, the capital of rump Sudan, which would seek to undermine its southern breakaway, or march back to war to reclaim some of its lost oilfields.

It was a seductive story that could be well told by handsome movie stars against the lavish backdrop supplied by South Sudan's superheated swamps and deserts and often beautiful people. But the narrative – part truth, part wilful misunderstanding – was deeply flawed. This would have mattered less if it had only informed public opinion, but instead it found its way into the building of a state.

Sudan, the former British colony that became Africa's largest state, has been in a condition of slow-burning internal conflict almost since independence in the 1950s. The second instalment of civil war was ended by the comprehensive peace agreement signed in 2005. The deal provided for a cooling-off period of six years before a loosely geographically defined south would be given the chance to vote on secession from the north.

The war had been brought to life in the US by broadcast evangelicals such as Billy Graham, who cast it as a heroic battle by Christian and African underdogs against a more powerful Muslim and Arab foe. The fact that religious and geographical lines were never remotely this clear and clean-cut was routinely ignored. The Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), under the leadership of the charismatic John Garang, was not fighting for an independent south but a democratic "new Sudan". Its forces were drawn from areas far beyond what are now the borders of South Sudan. And its battles were, for the most part, not against the national army, the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) but against rival militia groups, often drawn from the same great southern tribes, such as the Dinka and Nuer, that the SPLA leadership came from.

Much of the fighting and dying took place in the south, often with funding and encouragement from the north. This meant that a new country would have to be built in what had been the main theatre of the war, with a nation drawn from opposing sides in much of that conflict. No serious effort was made by any side in the post-2005 cooling-off period to reconcile the north and south. The US, Europe, the UN and the south's near-neighbours, Ethiopia, Uganda and Kenya, all pushed for the country to be broken up. This effort was formalised in a referendum in 2011.

The pursuit of separation at all costs made it harder to admit certain truths such as ethnic divisions and created the need for the "big lie", as one senior UN official calls it. "The big lie is that there was no ethnic problem in South Sudan. There is a political problem."

The midwife to the state-building was the UN peacekeeping mission – now known as Unmiss – a sprawling operation costing roughly $1bn a year. A further $1bn in development aid was pumped in annually by donors such as the US and Britain. As it was believed that there were no entrenched ethnic issues to overcome, the mandate for Unmiss – when it was drafted by the UN security council – framed the challenges for the new country as purely developmental. The choice of Hilde Johnson, a former Norwegian minister of international development, to head the mission reflected this.

While demobilisation and disarmament schemes were announced, for much of the time between 2005 and the referendum governing consisted of farming out oil and aid money to civil-war-era military commanders in order to keep the peace. Little was done to break up old units and forge a truly national army. The SPLA had become a big tent into which armed ethnic militias with no uniform, training or shared identity had wandered in order to get paid.

The complete dysfunction of South Sudan's government since independence in 2011 was largely ignored. When the president, Salva Kiir, accused his own government of looting $4bn in state assets and foreign aid money, little was said. When Kiir, who is from the south's biggest ethnic group, the Dinka, began to entrench its power at the expense of other communities, creating what people called a Dinkocracy, the UN said nothing. In the meantime Johnson, who is criticised by her own staff in private for being too close to the president, trumpeted the need for "service delivery", even as a vicious power struggle raged in the ruling party.

While critics argue that the prime focus should have been security instruments (the army) and executive instruments (the government), all the talk was of democracy, human rights and development – even though this was rarely matched by any action.

"You can't do that if the elites are arguing and trying not to kill each other," said the senior UN official, on condition of anonymity.

"A lot of people who knew about state building in Africa were screaming bloody murder."

When Kiir sacked his entire government to pre-empt a political power grab by his vice-president, Riek Machar, an ethnic Nuer, from South Sudan's second most populous group, the international community chided him half-heartedly. As both sides mobilised their supporters along ethnic lines and prepared for a renewed conflict, the UN and diplomats continued to refer to the increasingly autocratic president as "steadfast".

When fighting finally broke out on 15 December and elements of the presidential guard went house to house in the fledgling capital, Juba, murdering Nuer civilians, the talk was still of a political not an ethnic conflict. When Nuer youths who mobilise under the banner of the civil-war-era White Army overran a UN outpost, killing two peacekeepers and murdering Dinka officials, it was blamed by some on media inciting tit-for-tat attacks.

Jok Madut Jok, an academic and former culture minister, who had been one of the most passionate exponents of South Sudan, was among many intellectuals who railed against international reporting of the ethnic slaughter as irresponsible and lacking in context.

After visiting Nuer colleagues among the 63,000 South Sudanese who had gone into hiding in UN bases around the country, he described in an open letter how he had wept by the roadside: "My Nuer friends are very scared and will not even fathom returning to their homes, given what they saw during the fighting in Juba. But their present circumstance is humiliating to them, big army officers, senior government officials and university students who feel they cannot be safe in their own capital city in which they have lived for many years."

Much trumpeted peace efforts remain just "talks about talks", according to diplomats involved. Both sides are dusting off veterans from the 1990s – the era of the most deadly fighting. A battle looms for the oilfields of the ironically named Unity State, currently held by rebels under the former vice-president.

After years of denial from the international community, the only way out of a repeat of past wars will be another round of payoffs to military commanders and a reluctant return to square one on the state-building board, accompanied by an admission of past failures.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion