Amiran Natsvlishvili is not complaining about the kidnapping. Nor about the brutal beatings, or the huge ransom his family had to pay for his release. The former managing director of a state car plant in Georgia is not bitter, either, about the accusations of embezzlement and misuse of public funds.

No, as his young lawyer argues in a bright, high-ceiling courtroom in Strasbourg, what Natsvlishvili really objects to is that the state lied to him.

Locked up for more than four months in the same vile cell as the man who kidnapped and beat him as well as a convicted murderer, when the state finally offered him a deal – cop a plea, pay a fine and you're free – Natsvlishvili was so desperate that he jumped at it. And then he was told he could not appeal.

That is why we are here, says the lawyer to the judges behind the bench at the European court of human rights: this man has plainly been denied the right to a fair trial. Georgia of course denies it, but it is in breach of article 6, paragraph 1 of the European convention on human rights.

Along with the European commission in Brussels, the Strasbourg-based ECHR could reasonably lay claim to being one of the most maligned institutions in Britain. ("Hardly surprising, I suppose," quips a senior British court official. "Our name contains the words 'European' and 'human rights'. Not exactly a winning combination.")

Conservative MPs have said it is high time for Britain to "quit the jurisdiction" of a "supranational quango". The justice secretary, Chris Grayling, is "reviewing Britain's relationship" with an institution he says has "reached the point where it has lost democratic acceptability".

Grayling said last week the ECHR did not "make this country a better place". David Cameron has said the court risks becoming a glorified "small claims court" buried under a mountain of "trivial" claims , and suggested Britain could withdraw from the convention to "keep our country safe". The home secretary, Theresa May, has pledged the party's next manifesto will promise to scrap the Human Rights Act, which makes the convention enforceable in Britain.

Former lord chief justice Lord Judge and three other senior British judges have recently backed this stance in high-profile lectures, arguing that by treating the convention as a "living instrument" the ECHR is "undermining democracy". Its judges, rather than parliament, are now making British law, they allege, and parliamentary sovereignty should not be ceded to "a foreign court". But another leading supreme court judge, Lord Mance, last week forcefully defended the ECHR's contribution to British law.

Parts of the press have been more outspoken, railing against "meddling, unelected European judges" who are "wrecking British law" and demanding the government "draw a line in the sand to defend British sovereignty" by "defying Europe … and ignoring the rulings of this foreign court".

That's not how they see things in Strasbourg. In the 60 years of its existence, the ECHR has reached well over 10,000 judgments in cases such as that brought by Natsvlishvili, prompting changes to national laws and procedures in nearly 50 countries that have now signed the convention.

In the past decade, the court has required Bulgaria to care properly for people with mental and physical disabilities, and Austria to allow same-sex couples to adopt each other's children. It has forced Cyprus to take action against sex trafficking and Moldova to halt state censorship of TV. Its judgments have compelled improvements in Russian prisons, and more effective punishment of domestic violence in Turkey.

In France, laws have been passed to protect domestic servants from forced labour, while illegitimate children now have equal rights to inheritance.

Britain has been obliged to take greater care of vulnerable prisoners, regulate the monitoring of employees' communications, protect the anonymity of journalists' sources, bring the age of consent for gay people in line with that for heterosexuals and force local councils to observe proper safeguards in evictions.

"It isn't just about the human rights of individuals," says Paul Mahoney, the court's veteran British judge, "it's about the functioning of the rule of law – of democratic institutions – in countries not all of which have, like the UK, enjoyed 300-odd years of democracy and freedom.

At the end of the day, it's possible for somebody from a tiny village to come here, take their government to court and get the law changed. That really is a small miracle."

Deputy registrar Michael O'Boyle is equally forthright. "For six decades," he says, "this institution has radiated a highly impressive body of case law out to the legal systems of a large number of countries – 47 today. It's an advance in civilisation."

So: a "small miracle", an "advance in civilisation", or a meddling foreign body undermining national sovereignty. What is the ECHR?

The convention over which the court watches was drafted in the late 1940s, to protect Europeans from abuses piled on them over preceding decades. Britons were prominent in the drafting: without the likes of Ernest Bevin, Winston Churchill and David Maxwell Fyfe, the ECHR would not exist in its current form.

It secures, first and foremost, the right to life, a fair trial, freedom of expression, thought, conscience and religion, but also respect for private and family life and the protection of property. It prohibits torture, degrading treatment, forced labour, unlawful detention and discrimination "in the enjoyment of the rights and freedoms" it guarantees.

It has evolved over the years, interpreting those rights in situations its postwar drafters could scarcely have imagined: the day after Natsvlishvili v Georgia came Hamalainen v Finland, the case of a male-to-female transsexual unhappy that because same-sex marriage is forbidden in her country, her new gender could not be fully officially recognised unless she divorced or turned her religious marriage into a civil partnership.

The court – not the same as the Luxembourg-based European court of justice, which rules on the application of European Union law – sits in the eastern French (and, historically, occasionally German) city of Strasbourg, in a striking building by the British architect Richard Rogers.

It is open to a startling 800 million people, from Portugal to Siberia, all of whom can apply here if they feel their rights have been violated; equally startlingly, about 70,000 a year do.

So it is not, as one senior judge observes, your average court: "Other courts deal with demands in justice – guilty or not guilty. This one deals with demands for justice. Its job is to signal a dysfunction in the rule of law."

Down in the mail room, Nigar Shukurova points to an array of teetering piles. Each day, she says, the ECHR receives about 1,600 items of post, from scrappy handwritten letters addressed to the "Office Council Court of Europe" to foot-high dossiers "An den Kanzler des Europäischen Gerichtshof für Menschenrechte".

Perhaps 5% of cases fall at this hurdle: forms are not filled in, or the documentation never arrives. Most go on to be examined by judges, who sit singly to decide if a case is admissible and in committees – including, for the most complex, the 17-judge grand chamber – to examine its merits.

Only 30-odd cases a year get a public hearing; the overwhelming majority, maybe 90%, never get anywhere near that far, thrown out because they do not concern a convention right, or because the applicant has not personally been disadvantaged or exhausted every possible legal avenue at national level.

"We have to be a bit brutal," says one senior court official. "We can't afford to be sentimental."

This makes for a lot of disappointed people. Across the road from the courthouse, small but determined camps of Kurds and Chechens protest; on the morning of every public hearing, an outraged Romanian pensioner parades up and down with a placard.

"You are not a human rights institution," he bellows. "You are corrupt, rotten. From Satan! I want my pension, nothing else. Why have you thrown out my dossier? You have no souls."

It's a reminder, says Karen Reid, head of the filtering section – set up in 2011 to speed up the processing of cases – that however ill-founded the case, there is a person behind it.

"We've been called a lot of things," Reid says. "The European committee for the prevention of human rights, scum of the earth … But we've also been asked to legalise cannabis. And declare an independent kingdom of Sussex."

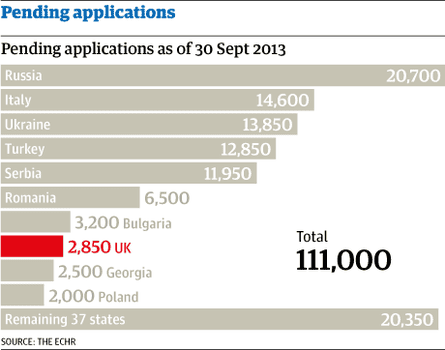

The filtering department is steadily helping the institution reduce a backlog – more than 160,000 cases at its peak, in November 2011 – caused by the avalanche that arrived with the collapse of the former eastern bloc.

The new system seems to be working: in the first nine months of 2013, the court decided 9% more cases than in the same period last year and cut the backlog by 13%; another two or three years and they hope to have got rid of it altogether."We're getting there," says Erik Fribergh, the registrar, who is in charge of a €67m (£56m) budget and a 650-strong team of lawyers and administrators serving the court's 47 elected judges (one from each country). "We can always do better. But we're making solid, quantifiable progress."

Once admitted, cases are prioritised, with those involving people at immediate risk or identifying potential systemic problems at the top of the pile.

Many others resemble each other and raise similar points of law: they are considered together, or tackled through pilot cases. Others, known as WECLs, concern well-established case law and can be dispatched by small committees of judges.

By streamlining its work like this, the court's judges delivered nearly 1,100 judgments last year; decisions on admissibility were made on a further 88,000 applications.

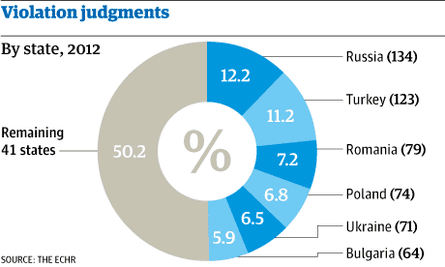

Some rights, it seems, are more often abused than others. In 2012, nearly a third of violations concerned the right to a fair trial – either because the trial concerned was plainly not fair or, often, because proceedings took too long. A further fifth involved allegations of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment. About 5% concerned the right to life.

And some countries' names recur more frequently than others. More than half the cases sent to judges involve just four: Russia, Turkey, Italy and Ukraine. The same countries – minus Italy, but plus Romania, Poland and Bulgaria – accounted for almost half the violation judgments delivered last year.

The court's caseload, in fact, reflects the diverse failings of Europe's various national judicial systems: the vast bulk of the 14,500 cases pending against Italy, for example, concern the inordinate length of Italian judicial proceedings, which can drag on for decades. The same applies to Greece.

"This is by far the biggest group of Greek cases," says the court's Greek judge, Linos-Alexandre Sicilianos.

"But the most important group concerns the detention of asylum seekers in special centres, often in degrading conditions. That's how the issue of immigration comes before the court and it's a major problem for Greece."

Applications from Serbia, which account for 10% of the total, stem mostly from the dissolution of former Yugoslavia: payment of army reservists, access to savings in present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, pensions in Kosovo.

In many former Soviet bloc countries, such as Ukraine, nonenforcement of domestic court decisions is one of the biggest problems: a local court says X must get their pension, and X never does.

With more than 20,000 cases pending, Russia is a case apart. "It's a big country," says Olga Chernishova, who heads the Russian case-processing division, "with big issues."

Often, perhaps surprisingly, the law itself is not at fault: it's about the facts: "If someone spends a year in pre-trial detention, in a cell with 15 people, with no running water, no fresh air and no exercise – that's a violation."

But like officials from most other countries represented here – with the notable exception of Britain – Chernishova acknowledges a "general consensus" in her country, in both the media and among the legal profession, on the value of the court's judgments.

Concrete changes in Russian law show the ECHR is making a difference, she says: a compensation system has been introduced for those affected by the non-execution of domestic judgments, a problem that has hurt "perhaps hundreds of thousands of people" in Russia.

There are new laws on prison overcrowding, and the removal of ubiquitous, daylight-obscuring shutters from prison cell windows. Russian courts are working quantifiably faster than they did 10 years ago; and the supreme court has explained to lower courts the difference between fact and opinion, so fewer journalists get banged up for libel.

Most tellingly, Chernishova says, Russian constitutional court rulings now routinely make reference to ECHR judgments: "And you really cannot underestimate the importance, the message sent to ordinary people when justice is finally done in cases – police brutality, for example – that domestic courts have delayed, or failed even to consider."

Inevitably, there are rulings Russia and other countries find somewhat more difficult to accept. As another judge puts it: "Our judgments tend to fall into two categories. It's either: we don't question your norms, but your system has malfunctioned. Or it's: sorry, we can't accept your norms. States generally accept the first quite readily. They don't much like the second."

In the past three years, Russia has accounted for half the ECHR's right-to-life violations. The vast majority relate to the pre-2006 "active anti-terrorist phase" of the conflict in Chechnya: disappearances, torture, extrajudicial detention, excessive use of force.

Politically, these judgments are hard for the Kremlin to swallow, and it has sometimes simply refused to co-operate. But even here there has been progress: two months ago, Russia finally accepted it used disproportionate force during a three-day artillery assault on a Chechen village that left 18 of the applicant's relatives dead, and failed to investigate.

"Now they will sometimes accept even these kind of judgments," Chernishova says. While democracy in Russia clearly has its challenges, she says people there "are telling us all the time that things could be much worse – much worse – without this court".

Which, of course, makes the attitude to the ECHR of the British government, and parts of the British press, all the more puzzling. "Actually, it's frankly quite dangerous," says Ineta Ziemele, the court's Latvian judge. "Coming from one of the court's founding members, it can make other governments, especially perhaps those in countries that may be rather less democratic, less concerned with human rights than the UK – it can comfort them. They can say: 'Britain doesn't accept your judgments; why should we?'"

Part of Britain's attitude can be explained simply by a different conception of the law. In continental Europe, judges – guardians of written constitutions – routinely overrule politicians. In the UK, parliament rules: primary legislation cannot be questioned by judges.

Partly too, it stems from a few high-profile recent cases that have not gone the government's way: the court's initial refusal, for example, to allow the deportation to Jordan of Abu Qatada, and its insistence that it is wrong to deny all prisoners, in every circumstance, a right to vote.

Mainly, though, Britain's current attitude seems to be informed most strongly by the wider problems of its relationship with Europe, and the belief among many Conservatives that loudly defending "British sovereignty" and attacking all things European will not lose them any votes. Essentially, in other words, it is political.

But whatever is driving it, Britain's stance is viewed in Strasbourg with alarm. Other countries have objected, sometimes forcefully, to individual judgments: Spain erupted last month when the ECHR ruled Madrid was wrong – as many legal experts had warned it – to apply retroactively a new law requiring prisoners serving long sentences to do the maximum 30 years.

That judgment prompted the release of, among others, a Basque separatist bomber – and howls of outrage from the press and some politicians.

But unlike David Cameron, Spain's prime minister, Mariano Rajoy, conceded that while he found the ruling "unjust and wrong", he had no choice but to comply.

Only Britain objects so strongly to a small number of ECHR rulings that it is contemplating pulling out of the convention altogether – and engaging at the same time in what many in Strasbourg, including senior British officials, see as a deliberate and often dishonest campaign against the court.

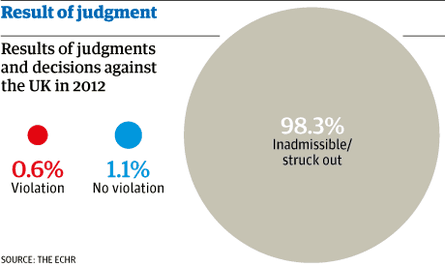

Last month, for the first time, the ECHR publicly expressed its concern about "frequent misrepresentation" and "seriously misleading" British press reports of its activities. Clare Ovey, head of the UK case-processing division, points out that of the 2,082 complaints against the UK dealt with last year, the court rejected 2,047 as inadmissible. It found no violation in 23, and upheld 12 – just 0.6% of the total.

Of the 2,500-odd potentially admissible cases pending against the UK, she adds, nearly 2,300 concern prisoners' voting rights (the remainder mainly involve the undue retention of DNA samples and criminal records data, expulsion cases, notably to Iraq, and complaints about indeterminate sentences).

True, a relatively high proportion of UK applications are by people convicted of a crime, but that's "mainly because Britain is an advanced democracy, where fundamental rights are largely respected. Other countries are not so lucky; there, this court plays a huge role in simply ensuring the rule of law is applied."

And whatever impression British newspapers may create, UK cases are not confined to criminals and terrorists: former Formula One boss Max Mosley saw his privacy complaint rejected; BA employee Nadia Eweida, who wanted to wear her crucifix at work, went home happy.

"This court has made so many positive UK judgments," says Ovey. "On press freedom, surveillance, deaths in police custody, admission of evidence, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender rights, corporal punishment in schools, protection of children … It is worrying, when you see that it is so misrepresented."

The court's determinedly anglophile president, Luxembourg judge Dean Spielmann, is diplomatic but plainly concerned. Far from exporting European values to Britain, he points out, the court has helped import British values to Europe.

"The right to be assisted by a lawyer at the first police interview, for example," he says. "That's a well-established principle in UK law, now widely accepted." Talk of withdrawing from the convention undermines "those who seek to improve human rights elsewhere in the world" and could pose real problems in British courts that today make "extensive and absolutely exemplary" use of ECHR case law in their own findings.

Official after official stresses that the European court of human rights does not "dictate" how governments should implement decisions. Rather, judgments invite states to find solutions to situations collectively deemed unacceptable.

"We are," says Spielmann, "really extremely sensitive. We realise every country is different. We don't say what states must do; we accept they each need the widest possible margin of appreciation to implement judgments."

What the court does say, though, is – for example – that a blanket voting ban on every single prisoner is not consistent with the convention by which Britain is bound (a view a parliamentary joint committee emphatically endorsed last week, saying the government had failed to advance a "plausible case" for maintaining the ban and the arguments for lifting it were "on any rational assessment, persuasive".)

But other countries mostly take the rough with the smooth: there is a wider good. So he regrets Britain's current "exceptional" position.

"It flies in the face of our shared responsibility," he says, "this joint effort to set – and to uphold – certain minimum standards for human rights, across a continent."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion