Editor’s Note: James Smith is CEO of Aegis Trust and Freddy Mutanguha is Country Director for Aegis in Rwanda, and a survivor of the 1994 Rwandan genocide. The Trust is an international organizational working to prevent genocide. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of James Smith and Freddy Mutanguha.

Story highlights

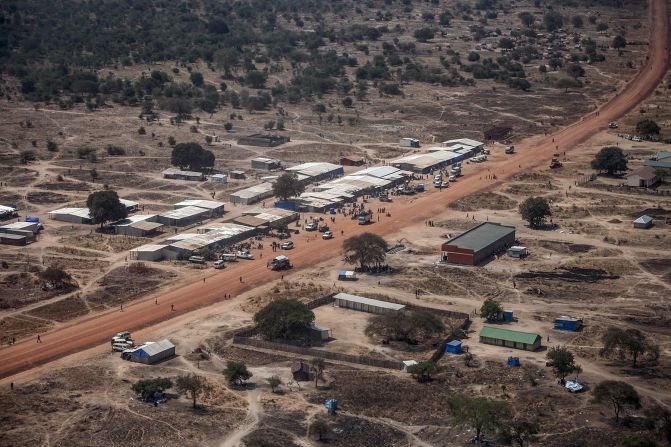

Africa's newest nation, South Sudan, is on the brink of civil war and possibly genocide

The violence in South Sudan has many likening it to the Rwandan genocide of 1994

Survivor Freddy Mutanguha says the two situations have many similar warning signs

To overcome risk of civil war South Sudan must develop a national not tribal identity

Several mass graves have been discovered, at least 1,000 people are dead and tens of thousands have been displaced in South Sudan as a recent outbreak of inter-ethnic violence has Africa’s newest nation on the brink of civil war and possibly genocide.

At the time of South Sudan’s independence in July of 2011 – free from Sudan and recovering from decades of civil war – hopes were high.

Southern Sudanese referred to their new country as the Promised Land. There were fears that Sudan might seek to undermine the new nation’s stability, but analysts cautioned the greatest threats to peace could come from within the country’s own borders.

As tensions rise between the South Sudan’s two largest ethnic groups, the Dinka and Nuer, commentators are now recalling the events in Rwanda with reference to this crisis.

Twenty years ago, in the New Year of 1994, reports warned of the threat of genocide in Rwanda as the radical Hutu government incited hatred against the Tutsi.

Less than six months later, the government of Rwanda had organized the murder of their Tutsi civilians, leaving around a million dead.

Preventing a devastating civil war from gripping South Sudan is urgent, but focus must also be given to preventing genocide, which is a high risk should instability in the country deepen.

The intentional nature of genocide and the attempt to destroy groups based on their ethnic, religious or national identity, make it a uniquely horrific crime and one that the international community has committed itself to prevent and punish.

Fear of escalating violence in South Sudan has led the United Nations Security Council to increase the peace-keeping operation in Sudan by a further 5,500 personnel.

In the experience of one of the authors, who lost many of his family in Rwanda 1994, they are right to do so.

According to genocide scholar, Barbara Harff, the risk of mass atrocities increases with political instability, the existence of an autocratic regime, a dominating ethnic group and previous genocide or massacres.

All of these factors were present in Rwanda preceding the genocide and are now present in South Sudan. Should South Sudan become entrenched in civil war, the risk of mass atrocities occurring will increase significantly.

While the parallels between Rwanda and South Sudan are not identical, they share some of the same warning signs, which we have outlined below:

The current crisis in South Sudan began as a power struggle between President Salva Kiir, originating from Sudan’s Dinka majority, and its former Vice President Riek Machar of the Nuer tribe.

Machar was ousted from his position by Kiir in July along with the rest of the cabinet.

The situation came to a violent head on December 15 when rival army factions loyal to the two leaders first clashed in the country’s capital of Juba.

The conflict has since spread throughout several states. Both sides have been accused of targeting members of the opposing ethnic group.

While different in the detail, power struggles mixed with an ethnic dimension was a feature in Rwanda in 1994.

Aside from the civil war, in which the Tutsi dominated Rwanda Patriotic Front were attempting to oust the Hutu Power government, there was an extremist factions within the ruling Hutu regime who consolidated its power by killing many Hutu opposition members as that same time as the genocide against the Tutsi began.

Massacres have already taken place in South Sudan.

As we saw in Rwanda, massacres of Tutsis occurred long before all out genocide, but failed to be seem as an alarm.

In South Sudan, the discovery of one mass grave in the town of Bentiu and two more outside of the capital should be viewed as indication of what could continue or escalate if the situation stays on its current trajectory.

In a concerning development, an armed rebel militia has now entered the fray in South Sudan. The militia – known as the “White Army” for dusting their bodies with ash – is reportedly composed of 25,000 Nuer youth and is suspected of being aligned with the rebel army and Machar.

The White Army attacked a United Nations peacekeeping base that was sheltering civilians, killing several peacekeepers on December 19.

The group has been known to make statements about their intent to wipe out members of rival ethnic groups.

In Rwanda, a militia aligned with the Hutu-led government known as the Interhamwe, expressed a similar ideology to the White Army and was harnessed by the political leaders to commit genocide.

The root causes of the crisis in South Sudan are deep set, but not insurmountable.

While there are differences in the context of the two crises, Rwanda’s not too distant past provides a warning that there is no time for complacency in South Sudan.

But, we should not only look back 20 years for lessons. South Sudan should look to Rwanda 20 years after the genocide to see how governance, rule of law and leadership have enabled development.

South Sudan could learn also how in Rwanda, resilience against violence is being reinforced at a community level through peace education that works to overcome the hostility and fear between groups and to develop an identity and purpose based not on tribe, but on the nation.

To do this takes true leadership from all concerned. Let us hope, that for the sake of South Sudan’s people, their leaders will not come to realize the solution to creating sustainable peace after countless dead have been buried.

Read more: What you need to know about South Sudan conflict

Watch more: Violence halts oil production

Read more: Rwandan restaurant hopes to heal the scars of genocide

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of James Smith and Freddy Mutanguha.