In the end, it wasn't the wind or the rain that demolished Estrella Moro's house. It was a large ship, sprung from its moorings, that ploughed straight through the neighbourhood, breaking the wood-and-iron houses in its path like toothpicks.

So there is something bitterly ironic that today it is the same ship, the Eva Jocelyn, that offers shelter to Moro and hundreds of other Filipinos made homeless by typhoon Haiyan.

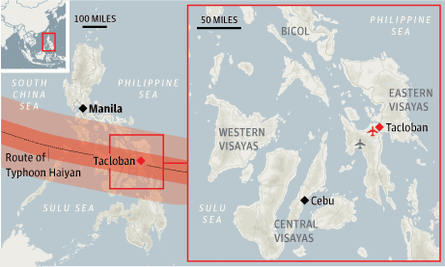

Their parlous shelter, in the lee of the blue and red vessel, is testimony to the stop-start progress in rebuilding Tacloban, a city of 250,000 people, three months after one of the most powerful storms ever recorded obliterated it, claiming 6,200 lives.

"The water came in seconds, reaching up to my neck and I started swimming," Moro recalls. "While I was swimming I saw the ship ramming into my house. I was swept out but I clung to a banana tree – if it wasn't for the tree, I would be gone." Her mother, sister-in-law, niece and uncle all died in the storm.

In Tacloban itself, a semblance of normality has returned. The traffic is heavy once more, the street markets by the port are well stocked with vegetables and fish, and banks, shops and petrol stations are open.

But parts of Tacloban are still a mess. And the reconstruction effort is being hampered by a long-simmering feud that pits two of the Philippines' most powerful political clans against each another.

On one side is the Tacloban mayor, Alfred Romualdez, scion of the Marcos clan that ruled the Philippines in the 1980s. On the other is the current president, Benigno Aquino, whose father was assassinated under Ferdinand Marcos's rule in 1983.

The area by the airport, surrounded on two sides by water, is particularly grim. Hundreds of white tents with UN markings line the road, many buildings are missing roofs, debris lies by the road, and power lines are keeling over. Most buildings bear the signs of damage from strong winds.

The only tall buildings to have survived relatively unscathed are the churches – although one archdiocese is badly damaged. Bodies are still being found in the rubble.

In rural areas, huge numbers of coconut trees – an economic lifeline for poor farmers – have been destroyed. Even those still standing are so damaged that they will no longer bear fruit.

The UN development programme is preparing a major effort to clear the debris, and sell the wood for lumber which would help farmers survive, while developing a long-term plan to encourage diversification into vegetables and legumes to grow alongside the coconut trees. But that will depend on donor funding at a time of ongoing emergencies elsewhere – from Syria to South Sudan – that is stretching budgets.

Tacloban's most pressing need is temporary or permanent shelter for 50,000 people whose homes were destroyed or are unsafe. About 1,000 live in a stadium, while others are in schools or tents. The mayor, Romualdez, had initially pledged to rehouse everyone by December. The city is putting up bunkhouses – wooden barrack-like buildings – but they are not going up fast enough.

Romualdez has voiced his frustration at the Philippine government's reluctance to release funds to help resettle those still living in temporary shelters. His other major concern is the lack of electricity, which is holding back the city's commercial resurgence. Only 20% of the town's power has been restored.

"The problem we have now is the people who were displaced and those who are staying in danger zones," said Romualdez. "They are willing to move, but unfortunately we don't have places to move them to. We have donors willing to provide homes, but we lack land. We have to develop sites for permanent and temporary shelter but we do not have equipment or money … Up to now, the government has not downloaded any funds whatsoever."

Romualdez is the nephew of Imelda Romualdez Marcos, wife of Ferdinand, and Tacloban and the surrounding Leyte province are political strongholds of the Romualdez clan. Bad blood between the family and the Aquinos has persisted for 30 years.

Asked whether politics lay behind the lack of national support for Tacloban, Romualdez chose his words carefully. "I would rather people see for themselves than for me to make that conclusion," he said after a long pause.

Others are not so diplomatic. Fred Padernos – who runs Radio Abante, a UN-funded project to get community feedback on the massive relief effort – It's very obvious why the people of Tacloban are being punished: it's because the mayor is called Romualdez."

Yeb Sano – the Philippines' climate negotiator, who firmly linked typhoon Haiyan to climate change – said he had mixed feelings about the disaster response. "We're seeing many different initiatives, and I'm heartened to see many things at local level," he said. "But in every disaster those who are poorest have very little option but to resume building their homes in danger areas. We should be pushing very strongly for a coherent land policy – on where there should be human settlement and where land should be used for food production."

Oxfam said the humanitarian response had saved thousands of lives but the poorest coconut farmers, traders and fishermen were being left out of the recovery effort. "Latest figures show zero funding has been allocated to the UN for coconut workers and fisherpeople, while the Philippines government has been slow to deliver the agricultural and reconstruction support it has promised," it said.

Moro has returned to the poor neighbourhood of Anibong to live under the shadow of the ship, despite a rule requiring people to live at least 40 metres from the water's edge. She is nervous about any relocation, fearing it will be far away from the city. But she no longer wants to stay near the water. "I want to leave this place so I can forget what happened," she said. "I can't believe I'm still alive."

Read more

Typhoon Haiyan sends coconut farming 'back to year zero'

Life after typhoon Haiyan: Cebu's struggle to rebuild lives and homes

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion