In July 2012, Ahmad Haidar saw a young man die at the hands of a Syrian army sniper on an Aleppo street.

The first shot had hit the civilian in the leg and onlookers felt it was a deliberate attempt to incapacitate rather than instantly kill, which Haidar says is a common tactic intended to lure out rescuers to target them too. Aware of this danger, the onlookers, unable to approach the victim, desperately struggled to pull him to safety using ropes and metal poles.

“He was trying to get behind cover and people tried to help with anything that was there,” Haidar recalls. The sniper fired again with a lethal shot to the neck.

The attempt to help was brave, but unprepared and badly equipped. Haidar thought there was something he could do to help.

Drawing on his expertise in electronics and computer programming - which he taught before the war – he devised a hi-tech response to Syrian president Bashar al-Assad’s snipers. The result: a caterpillar-tracked, remote-controlled robot equipped with large mechanical arms.

It is designed to pick up wounded people and place them on a stretcher inside an armoured compartment and move to safety. Haidar named it “Tena”, after a Finnish woman he once sat next to on a flight and “fell in love with for an hour”. He is now, he quickly adds, happily married.

Haidar and his childhood friend Belal, an engineer, have spent the past seven months fabricating and assembling Tena in a nondescript machine shop on the outskirts of a Turkish border town. Its robotic arms – the most complex and technically demanding component - are now complete. Next, they need a bulldozer chassis to mount them on.

Acquiring one will not be easy without some form of outside help. Haidar attempted to crowdfund the project on robotena.org but so far it has not generated the money required. As a result, he and his wife, Isabelle, have exhausted their personal savings to meet the robot’s construction costs.

A rebel group said it would provide a vehicle, but the machine was too large and offered only on the condition that Haidar create weapons in return. He refused. The duo has also discussed the project with various aid agencies, but have not yet been able to secure backing.

In the meantime, they are working on a metallic alloy-armoured shell to protect against small arms fire. Haidar expects that this will not be robust enough to keep Tena operational for long in Syria’s urban battlefields, but if it lasts to prove the ambitious concept is viable, he will be happy. “If she saves one person and shows it can be done, then it will all be worth it,” he says.

With his long straight hair and immaculate suit, Heider makes for a faintly incongruous rebel. But his background means he has valuable skills, and before he escaped Syria, he was part of a hacker group waging electronic war against the government’s Syrian Electronic Army (SEA).

The SEA, Haidar says, are a formidable enemy. He has seen their operations first-hand. In early 2011, a recruiter offered him a position with the group in lieu of mandatory military service and took him to a safe house located under a seemingly normal computer retailer in Aleppo’s Al-Furqan neighbourhood.

“It was another world in there,” he remembers. “They had absolutely everything, a lot of hi-tech gear.” Much of it, he adds, was US-made.

He declined the offer and went into hiding, then, when the uprising began, joined up with six other hackers and began to break into state-controlled websites. His role, he says, was making viruses. Characteristically, he named them after ex-girlfriends.

In April 2012, Haidar says the group managed to upload a breaking-news banner to the state-controlled Al-Dunya TV channel reporting that Assad had decided to step down “for the good of his people”. Anti-government protesters hit the streets in celebratory response to this high-profile security breach, carrying banners that said “Thank you, Pirates of Aleppo”. The hackers adopted the name. “It was like a medal of honour for us,” Haidar says.

The pirates also regularly broke into the Facebook profiles of activists arrested by the regime and cleaned up any evidence of rebellious activities. In their place, they uploaded explicit pictures to act as a distraction. “We would swap every revolutionary flag or phrase with pornographic photos to keep the investigators busy,” Haidar says with a smile. “It worked really well.”

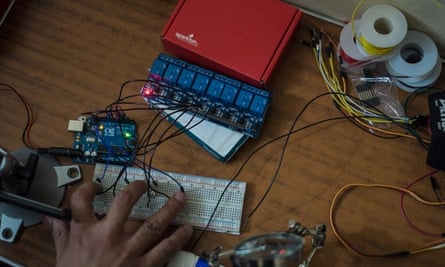

Haidar fled to Turkey when the battle for Aleppo intensified in September 2012 and for a time worked as a “fixer”, arranging visits into Syria for members of the press. His spare moments were spent planning the robot’s development and constructing its control system, which he says will allow it to be operated from as far as almost two miles away.

Tena now has his undivided attention - the rise of extremist groups in Northern Syria means that it is almost impossible for foreign journalists, as well as local journalists, to work there. When the project is finally finished and functional, Haidar plans to move to France, where Isabelle currently lives. “I’ll be on a farm with three dogs and the woman I love,” he says happily. Until then though, there is work to be done.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion