Scientists have discovered a frozen underworld beneath the ice sheet covering northern Greenland.

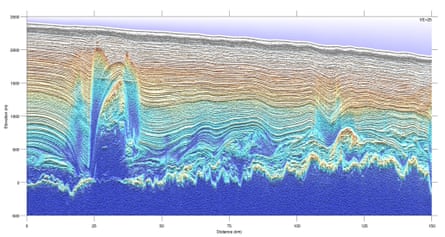

The previously unknown landscape, a vast expanse of warped shapes including some as tall as a Manhattan skyscraper, was found using ice-penetrating radar loaded aboard Nasa survey flights.

The findings and the first images of the frozen world more than a mile below the surface of the ice sheet are published on Sunday in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Scientists said the findings could deepen understanding of how the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica respond to climate change.

“We see more of these features where the ice sheet starts to go fast,” Robin Bell, the study's lead author and a geophysicist at Columbia University's Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, said in a statement. “We think the refreezing process uplifts, distorts and warms the ice above, making it softer and easier to flow.”

Until recently, scientists studying the Greenland ice sheet for evidence of change under global warming had thought the shapes they discerned beneath the ice sheet were mountain ranges.

But with sophisticated new gravity-sensing and radar operating from Nasa's airborne surveys of the ice sheet over the last 20 years, scientists eventually concluded the formations were ice – not rock.

The formations were caused by the melting and subsequent re-freezing of water at the bottom of the ice sheet and the scientists said they were initially stunned by the results.

“They simply look spectacular,” said Kirsty Tinto, a geophysicist at Lamont-Doherty. “Everything was just flat parallel lines. That is how ice is supposed to be. But here it is breaking all the rules. You get these crazy, folded, distorted, overturned, undulating things at the bottom of the ice, and they are the size of skyscrapers.”

The structures – some measuring up to 1km thick - cover about 10% of the surveyed areas of northern Greenland.

About a dozen were found around Petermann glacier in north-western Greenland, which has been undergoing rapid changes and two years ago calved an iceberg twice the size of Manhattan.

The melting and re-freezing at the bottom of the ice sheet has been underway for hundreds of thousands of years.

Scientists were aware of the process but until now did not realise the meltwater was re-freezing into complex formations.

The glacier warms under its own weight, producing meltwater that freezes and grows up into the forms around its base.

The process appears to accelerate the flow of glaciers, such as Petermann towards the sea, but Tinto said further study was needed.

“If we want to understand how ice is going to respond to climate change, we have to understand its fundamental dynamic,” she said. “It is not just that you are melting the surface and the surface is just running into the sea. There is a complicated and quite beautiful system running through the ice and you have to understand it top to bottom to understand what it is doing.”