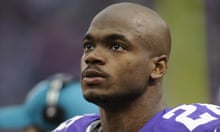

There are many possible reactions to reports that Minnesota Vikings running back Adrian Peterson beat two of his children. To return to the NFL’s obsession of ethics via optics, you could wonder why his teammates were dismissed from the Vikings after they were arrested, while until Wednesday morning Peterson was expected to play. You could even wonder why the Minnesota governor would call for Peterson’s suspension after, just a year ago, posing for a picture with a Vikings team owner who had been fined $85m for fraud for actions a judge labeled criminal racketeering.

But all those are abstractions – the NFL as hypocrisy, as undiluted power masquerading as moral strength, the normative state of the NFL at this point. Instead, if, like me, you are about to become a parent soon, and if, like me, you were disciplined physically as a child, you look at Adrian Peterson – the man who says “I disciplined my son the way I was disciplined as a child” – and you wonder the same thing:

Will I become that?

For a lot of people, the answer is clearly: It wouldn’t matter if I did. Click any Facebook post on the Peterson story, any tweet by a major publication on the topic, any newspaper’s comments section – hell, you could probably wait a couple minutes and read the comments here – and you will find someone saying: My daddy whooped the hell out of me, and I turned out fine.

From a smartassed standpoint, it’s easy to note that many of the people who claim to have turned out fine look or sound pretty clearly the opposite of fine. That such people unintentionally embody the antithesis of “fine” – that they remain unaware of embodying the emotions therein – makes their not-fineness double the distance between them and whatever passes for fine. And while that’s often true, it’s also a kind of cheap joke.

The pernicious, toxic and inescapable lifelong effect of being disciplined physically – either to the point of abuse, or to the point that the distinction between acceptable and unacceptable blurs in your mind – is that you almost have to say you turned out fine, just to redeem the fact of being who you are. That you “turned out fine” is the only way to make sense of having once felt total terror or uncontrollable shaking rage at the sight of one (or both) of the two people expected to care most for you in the world. The thought that you might have ended up relatively OK or perhaps even better without all that fear is almost unbearable: the suffering only doubles if you admit that it truly had no purpose.

I have had the “it made me who I am” conversation more times than I can count. As someone in his later thirties, I am probably from the last American generation where corporal punishment was widely tolerated among the middle class. As a child I thought nothing of seeing family members spanked harshly at gatherings, nor of friend’s dads countering displays of unapologetic backtalk with deadly-unfunny statements like, “Well, if you want, Jimmy, we can go upstairs and see if the belt agrees with you.” And nearly everyone’s dads told us the same thing, “You think your grandpa’s a sweet old man now, but he belted me harder than I’ve ever hit you.” This was an heirloom every generation gave to its next.

If anything, the ubiquity of other kids going through the same thing led many of my friends and I to the same conclusions: that somehow we were more chickenshit than our other friends, that locking yourself in the bedroom and pleading with one parent not to send you over to another parent’s home for their custodial visitation manifested some particularly unmanly cravenness. That this was so normal as to make your trembling anxiety not only aberrant but infantile. That your friend wouldn’t sit perfectly still in the passenger seat, utterly convinced that any motion in any direction for any purpose would ignite a sudden incendiary temper. That another friend wouldn’t visibly wince like a beaten dog when a parent’s arm unexpectedly came down, only to rest playfully across his shoulders. That, somehow, even the people being hit and terrorized as much or more than you were stronger than you.

It never fully leaves. Years later, you find yourself at a New Year’s party and idly ask a friend a question about dads, and after 10 minutes’ conversation you realize both of you are on the verge either of insensate bawling, or else ready to throw a chair through a window. Or you find yourself back in the old hometown at Christmas, talking a drunk high school buddy into getting back in the car because the house he asked you to stop at – one you didn’t recognize – is his dad’s new house, with his new family, and your friend is talking about how much he wishes he could just ring the doorbell and beat his father’s face into a gory smear, until it looks like someone dropped a tray of lasagna out a fifth-story window.

Or you find yourself at a college football party last weekend, and Adrian Peterson comes up, and a woman from out of town asks, “Do people in the south really do that still? How does it stop?” And a dude in his early thirties who looks like a 6ft-3in brick wall says, “Everyone on my block did that. It stops as soon as they realize you might be able to beat their ass just as good.” And without thinking about it, you kill the party for the next two minutes by saying, “It’s not just the south. I grew up in San Francisco. Sometimes nobody winds up bigger or stronger. Sometimes it stops because you move out. Or because you realize that if both of you don’t grow up, one of you is going to die.”

Or you find yourself anticipating holding your infant son in your hands and daydreaming about teaching him to walk and run and ride a bike and throw a ball and memorize his multiplication tables and plot the constellations, and then your vision grows ineluctably dark. And you think of the teenage years, of defiance for defiance’s sake, of assertive mockery and the contempt of selective deafness, of constant jockeying for power in a relationship suddenly destabilized – of this fathers-and-sons thing that stretches back 152 years to Turgenev and a further 2,500 years to Exodus, Leviticus and Deuteronomy. And you wonder if you will ever reach that point of pure frustration with your child that you saw on a parent’s face – the one that transformed almost with pleasure at the moment that you crossed the line that let him hit you, that gave him that moment of something almost like relief at being able to end the negotiations and finally just slap the defiance out of your stupid fucking mouth.

And you’re glad of who you are, and you’re glad of this moment of becoming a father, but you wonder how fine you really turned out. You can’t say you turned out any other way, because you really are proud to have achieved this much. But you can’t escape the knowledge that many of us – even the best of us – are only as good as the tools we’ve been given. And you know that the one you were given again and again is that violence ends the conversation, and the lesson – however larded with rage, resentment and murderous fantasy – is learned. And you look at someone like Adrian Peterson with the deep, haunting self-mistrust of knowing that he probably learned all his lessons from a beating too, and despite millions of dollars and every opportunity in the world, when he reached for a tool, the only one he thought to grab was a stick.