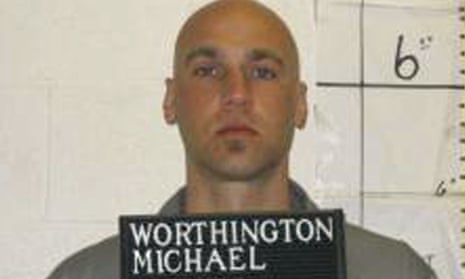

The first US execution since the drawn-out death of Joseph Wood is scheduled for Wednesday in Missouri, where Michael Worthington is set to die for the 1995 murder of a college student.

Wood took nearly two hours to die in Arizona on 23 July. Witnesses said that he gasped and gulped more than 600 times, and prison records show that he was given fifteen separate doses of midazolam and hydromorphone, which his lawyers said was in violation of the state’s executions protocol.

The manner of Wood’s death prompted an outcry by anti-capital punishment campaigners. His was the third execution to go awry this year, following troubled procedures in Ohio in January and Oklahoma in April.

After events in Arizona, the American Civil Liberties Union called for a nationwide suspension of executions and said in a statement: “It’s time to ask the question: How is it possible that, in 2014, state after state is utterly failing at lethal injection? How can it be, given modern medicine, that it could take hours instead of minutes for states to kill someone?”

Worthington, 43, pleaded guilty in 1999 to raping and strangling 24-year-old Melinda Griffin in Lake St Louis. His execution is scheduled to begin at 12.01am local time on Wednesday.

Wood was only the second inmate to be put to death using a midazolam and hydromorphone combination, while Missouri employs a single-drug protocol using pentobarbital. So does Texas, the nation’s most-active death penalty state.

Pentobarbital is a barbiturate often used to treat seizures and to euthanise animals. Since Ohio became the first state to execute a prisoner using only pentobarbital in 2011, the drug has developed a track record of killing death row inmates seemingly in an efficient manner that comports with the US constitution’s ban on punishments that cause excessive suffering.

So far this year, 14 executions have taken place using single-drug pentobarbital, six of them in Missouri, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. The state only executed four people between 2006 and 2013.

However, its use has not been without controversy. An Oklahoma inmate, Michael Lee Wilson, said he felt “my whole body burning” after being injected with the drug last January, while in Texas last April, Jose Villegas said “it does kind of burn”.

In common with other states, lawyers for Missouri death row inmates have issued legal proceedings in a bid to force officials to be more transparent about their drug procurement processes and lethal injection procedures.

The state said in a court document that it has carried out “eight rapid and painless” executions using pentobarbital since last year and so there is no reason to halt Wednesday’s event. But in a filing last month, Worthington’s attorneys argued that since Missouri has recently changed its protocol to become even more secretive – not even disclosing whether it conducts quality-control testing – he cannot be sure that the batch of compounded pentobarbital to be used in his execution is free from contaminants.

The federal eighth circuit court of appeals denied a motion seeking a stay of execution last week. But one judge, Kermit Bye, who has previously been a strong critic of Missouri’s processes, wrote a dissent which was scathing about the state’s secrecy and recent rush to execute prisoners even before all court proceedings are complete. Litigation involving Worthington and other Missouri death row inmates is ongoing, including one of first amendment grounds brought by the Guardian, the Associated Press and local Missouri media.

“If states are going to continue to impose this most severe of penalties, we should demand better than Missouri has done. We should expect a far more fair, sound, and transparent process,” Bye wrote on 1 August.

“The state should be open about the drugs it is using and the suppliers who supply them. The state should welcome outside testing of the compounded chemicals to ensure all constitutional requirements have been satisfied. In addition, instead of interfering with and frustrating efforts to have the process reviewed by courts and the governor of Missouri, the state should be actively assisting with those efforts …

“The state’s goal should be the fundamentally fair administration of a criminal justice system which actively strives to comport with constitutional requirements, instead of seemingly racing to the executioner’s gurney as quickly as possible and at all costs.”

Worthington’s lawyers on Tuesday launched last-minute appeals to the US supreme court, asking them to stop the execution until the ramifications of Wood’s botched procedure and of Missouri’s secrecy can be examined in more detail, Reuters reported.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion