"The brain is hot," says Dr. Eric R. Kandel, bow tie askew and eyes a-twinkle. The octogenarian Nobel laureate, who has never quite lost his Brooklyn accent, lists a number of recent efforts that suggest a renewed enthusiasm in trying to understand the most intricate mechanism in the human body: President Barack Obama's BRAIN Initiative, which will devote hundreds of millions of dollars to trying to understand "how we think, learn and remember"; a $200 million neurology research center at Columbia University, started via a 2012 gift by real estate tycoon Mortimer B. Zuckerman; a new $1 million Israeli prize in brain technology. Upon announcement of the last of these, former Israeli president Shimon Peres lamented that we still know so little about the brain that we remain "strangers to ourselves."

And then, of course, there was Ted Stanley's $650 million gift, in mid-July, to the Broad Institute in hopes that it can decode the genes responsible for schizophrenia, which affects Stanley's son Jonathan. The New York Times called Stanley's bequest "one of the largest private gifts ever for scientific research," while Forbes speculated that it could "kickstart psychiatry."

The large sums of money devoted to psychiatric research suggest that the discipline indeed needs a kick in the rear. Kandel, who won the 2000 Nobel Prize in medicine for using sea slugs to gain insight into memory storage and readily calls himself a "delusional optimist," admits that we've made "only modest improvements" in treating the most serious psychiatric illnesses, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. This is a widely shared view: In reporting on Stanley's million gift, the Times noted, "Despite decades of costly research, experts have learned virtually nothing about the causes of psychiatric disorders and have developed no truly novel drug treatments in more than a quarter century."

Kandel and other eminent researchers gathered in midtown Manhattan over a weekend in mid-July for a meeting of the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (BBRF), which annually awards grants to the most promising research projects in psychiatric medicine. The conclave proved a ripe opportunity to survey the field to see what's working—and what isn't.

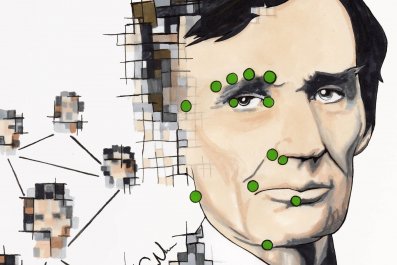

"My first view of a psychiatric patient," recalls Dr. Herbert Pardes of his training during the 1950s, "was of a naked man in a spare room in a state hospital, smearing feces all over the walls." Pardes, the former president of the American Psychiatric Association and chief of New York-Presbyterian Hospital and currently the head of the BBRF's scientific council, says we have come a long way from those One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest days, if not quite far enough. We know, for example, that dumping cold water on an ailing patient won't cure insanity, but despite the proliferation of psychiatric drugs in the second half of the 20th century, we are not sure what will. That's in large part because the brain, with its 86 billion neurons, remains deeply resistant to our understanding, despite recent advances in neuroimaging.

The best promise for psychiatric research, according to many at the BBRF scientific council meeting, is to understand the genetic basis of psychiatric illness. That mirrors the prevalent belief among cancer researchers that finding errant genes—and quashing their effects—is the best way to halt (or even head off) illness. The Stanley gift, for example, is explicitly intended to study DNA in hopes of decoding the genetic tranches where mental illness lurks. That gift came the same week that a paper in Nature hailed the discovery of "108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci." One of the authors of the study called the discovery a "revelation."

Similarly hopeful is Dr. Daniel R. Weinberger, who heads the Lieber Institute for Brain Development. Addressing the BBRF crowd with his raspy basso profundo, Weinberger said that this was "a watershed moment in psychiatric research" because we had finally begun to map out the "mechanisms of illness" that are genes. He joked that he'd stood in front of the same crowd many times before, similarly claiming that a "watershed" was at hand, only to be disappointed. But he was sure that, in this "century of genomic medicine," psychiatry was on the right track.

Of course, between the vastness of the human genome and the inscrutability of the brain, it could be many years before we fully grasp how aberrant genes produce specific illnesses, longer yet before we are able translate these insights into treatment. Kandel, for example, thinks it will be another century before we truly understand the human brain.

Which does not mean that we have to consign ourselves to the status quo. Pardes, for one, cites the "value of symptom relief"—that is, of alleviating mental ailments without necessarily having understood them. Patients, after all, are less interested in pure science than in whatever may cure their disease.

It is troubling, then, that few new psychiatric drugs are being developed. Last year,Science News reported that "major pharmaceutical companies are abandoning psychiatric drug development." The article lists several reasons: "Faulty assumptions, animal models that don't look anything like human diseases, hazy diagnoses and a lack of knowledge about how the brain works."

The lack of interest in what he calls "classical psychopharmacology" bothers Dr. Herbert Y. Meltzer, whose work led to the discovery of clozapine, perhaps our best weapon against schizophrenia. Meltzer, a member of the BBRF scientific council and a professor of psychiatry at Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine, "absolutely" disagrees with the notion that genomics alone holds the key. "Clinical pharmacology is in serious trouble," he adds, with few young investigators interested in the kind of work for which he became renowned. While that may simply be the result of shifting interests, it potentially deprives patients of new cures.

Despite the disagreements and the many unknowns that remain, Dr. Jeffrey Borenstein, the BBRF's president and CEO, believes that brain research is entering a "golden age," as he recently wrote in an op-ed for LiveScience. As many as 25 percent of Americans are afflicted with mental illness, he writes, whether that's war veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder or teenagers debilitated by depression. Long gone are the days, Borenstein writes, when people "viewed mental illness as demonic possession or witchcraft." And yet the brain continues to confound.