As darkness falls on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast, dozens of giant reptiles emerge from the sea and drag themselves laboriously onto the shore at Moín Beach.

Every night throughout the nesting season, from March to July, leatherback turtles crawl beyond the tideline to lay scores of eggs in holes laboriously scraped in the sand.

Each turtle can lay up to 80 of the cue-ball-sized eggs, but only a fraction remain safely in their nests: most are plundered by poachers who sell them on the black market as aphrodisiacs. It’s a lucrative trade for the poachers, but disastrous for the turtles, which have been pushed to the brink of extinction by the illegal trade.

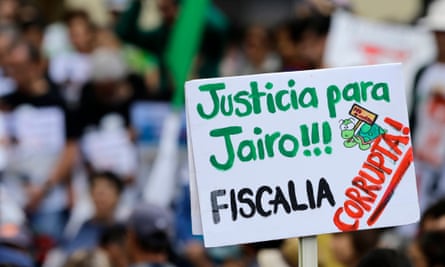

In recent years, conservationists have joined in the race to find eggs, which were reburied in a secure location. But frustrated poachers soon began to retaliate with attacks on the volunteers. In May 2013, the conflict culminated in the murder of 26-year-old conservation activist Jairo Mora. Kidnapped while collecting turtle eggs, Mora was beaten and dragged behind a car until he died of asphyxiation in the sand.

Seven alleged poachers were accused of the murder but all were acquitted on 26 January, and conservation groups, spooked by the slaying and the lack of justice in the case, have not returned to collect eggs on Moín Beach.

The turtles which have just started to arrive are now completely unprotected.

Mora’s brutal murder drew international media attention and made him a household name in Costa Rica. But few outside the environmental community know that Mora’s case joins a growing list of crimes against environmentalists in Costa Rica. Since 1989, the murder of 10 environmentalists have gone unsolved.

Such impunity has tarnished Costa Rica’s green image abroad, scaring off foreign volunteers and hurting tourism. Now environmental and human rights groups are calling for reforms to address the dangers these environmental protectors face on the country’s frontier.

Heading into trial, prosecutors on Mora’s case appeared to have an overwhelming amount of evidence on their side, but by the end of the three-month proceedings almost all of that evidence was found to be unusable. Investigators were found to have violated protocol, prosecutors had misfiled the telephone logs and evidence seemed to have mysteriously disappeared from the courthouse. Judges were forced to exclude large segments of the prosecution’s case. Ultimately, too much reasonable doubt was created for the prosecution to secure a conviction for the murder.

None of the exonerated defendants took the stand at trial to plead their innocence, and none have spoken publicly about the verdict – though one defendant, José Bryan Quesada, claimed he was innocent on a Costa Rican news station prior to the trial. In Costa Rica, a person can be tried up to three times for the same crime, but experts doubt that even a new judge will allow use of the evidence excluded in the first trial.

“At this point it is incredibly unlikely that anyone will go to prison for Jairo Mora’s murder,” said Alvaro Sagót, a Costa Rican environmental attorney. “I often get asked: ‘In Costa Rica, who protects the people who protect the environment?’ The answer is: no one.”

Sagót has led a number of cases against large development projects, and says he himself has received countless threats due to his work. And he is not alone: Costa Rica’s Federation for the Conservation of the Environment (Fecon) has recorded 66 crimes against environmentalists in the country since 2002. In every case, the victims said they were targeted for their environmental work.

The list features some relatively minor crimes such as vandalism, but it also includes assaults, robberies and murder.

Diego Armando Saborío, a 28-year-old law student, was shot dead in his home in the mountains of northern Costa Rica last October. Saborío had often spoken out against the illegal hunting rampant in his town, and prohibited poachers from hunting on his land. Several days before the murder, local poacher Miguel Pineda had allegedly hung a dead deer in Saborío’s door in what was viewed by many as a warning. Police named Pineda as the case’s prime suspect, but they were unable to find and arrest him.

Canadian Kimberly Blackwell was found shot dead in her home near Corcovado National Park in the country’s south-west in 2011. In the months before her murder, Blackwell had filed several complaints with police about poachers illegally entering the park to hunt. After nine months, police arrested a local man who neighbours claimed regularly hunted in the park. But in 2014, prosecutors dropped the case, declaring there was not enough evidence to convict him of the crime.

Environmental truth commission on horizon

The lack of convictions in these cases reflects a global pattern of impunity in crimes against environmentalists. A 2014 study by NGO Global Witness reported that between 2002 and 2013, 908 environmentalists were killed. At the report’s publication only 32 of the cases had a prime suspect, and only six resulted in convictions. This growing problem is especially acute in Latin America, but is all the more shocking in Costa Rica due to its reputation as an eco-friendly tourist hub.

“We’ve all been affected by the attention this has gotten,” said Didiher Chacón, the director of Latin American Sea Turtles (Last), the NGO Mora worked for before his murder. In the year after Mora’s death, Last had a 90% decrease in volunteers for their turtle conservation programs. “The fact is that we are conservationists, not police,” said Chacón. “Someone needs to protect us so we can protect the environment.”

But activists say that police often fail to take threats against environmentalists seriously, focusing their attention on more traditional crime.

When Costa Rica’s Judicial Investigation Police (OIJ) first made the arrests for Mora’s murder, investigators declared that the motive had nothing to do with poaching. Despite Mora’s feud with the poachers,OIJ director Francisco Segura said the killers were driven by “simple robbery”.

“Government officials often characterize deaths like that of Jairo Mora as regular crime,” said John Knox, an independent expert on human rights and the environment for the United Nations. “These cases are treated as one individual case after another, as a normal robbery or murder. This approach fails to acknowledge how these cases form a pattern.”

According to Knox, governments all over the world have failed to adequately address the growing safety concerns for environmentalists. In Costa Rica, experts sometimes attribute this failure to incompetence or a lack of resources, while others point to a more sinister desire to preserve the country’s image.

“The government doesn’t want to link these crimes with environmentalism,” Sagót said. “They don’t want to say that being an environmentalist is dangerous in Costa Rica because we are supposed to be the greenest, most eco-friendly country in the world.”

Rural poverty, a lack of police resources and the pressures of development all play a role in the rise of violence against environmentalists, but conservation groups say a solution cannot be found until authorities recognize that there is a problem.

“At the very least we want the government to see that this cycle exists,” said Mauricio Álvarez, the president of Fecon. “When you do that you can see the cause for this aggression more clearly and begin to address it.”

Shortly after Mora’s murder, Fecon and other conservation groups presented a plan for the creation of an environmental truth commission. The commission would examine each of the environmentalist murders in the past 25 years and create a plan of action to protect environmentalists in the future. The proposal is now up for consideration by Costa Rica’s legislative assembly, and if passed would be the world’s first.

“Right now the state is not fulfilling their obligation to protect the environment and environmentalists. We aren’t living up to our reputation as a green country,” Álvarez said. “With this we could really be that environmental leader. We could be an example for the rest of the world.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion