Dr. Terrie Taylor and her colleagues working in Malawi have seen comatose children diagnosed with cerebral malaria recover from the disease. They have also seen children's breathing suddenly become irregular and then stop as they succumb to the same disease—despite receiving drugs that kill the malaria parasite, blood transfusions and other standard treatments.

While drugs have been developed that kill the parasite, malaria can still be deadly for young children after treatment. And doctors have been less successful figuring out how to treat the effects of an infection—especially in the case of cerebral malaria, a particularly deadly form of the disease. Fatality rates among children with cerebral malaria in Africa range from 15 percent to 25 percent, according to Taylor's newly published paper, "Brain Swelling and Death in Children with Cerebral Malaria."

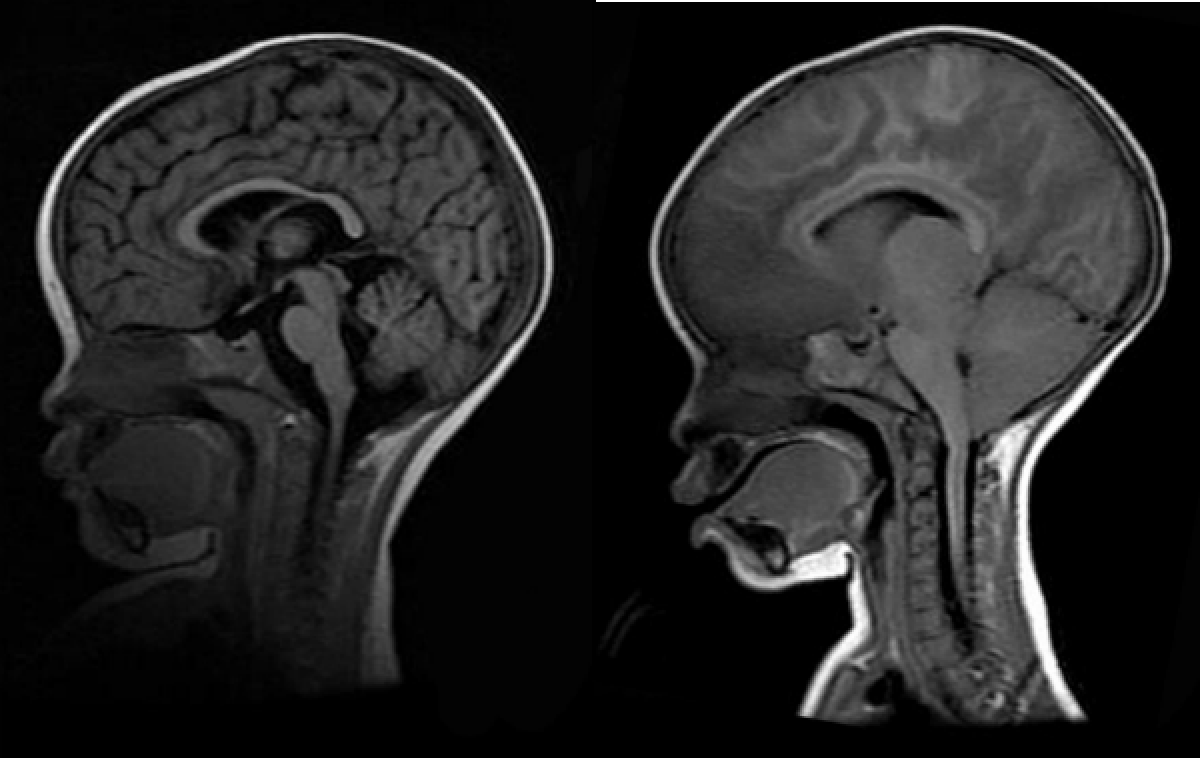

Until now, researchers had hypothesized but not confirmed why some children recovered while others died from cerebral malaria. In the study published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine, Taylor and her team describe more definitively and conclusively than previous studies what causes some children to die from cerebral malaria: The brain swells and eventually crushes the brainstem, which is where the neural stimulus for breathing originates.

The key to clearing up the uncertainty about the role of brain swelling in these deaths was refining the diagnostic criteria for cerebral malaria. It's easy enough to diagnose cerebral malaria after death: One can take a slice of brain tissue, look at it under a microscope and identify the telling signs of cerebral malaria. But identifying the condition in a living patient has been a major challenge.

The need for autopsy studies was particularly problematic in figuring out how exactly these children died because in order to gain access to the brain in an autopsy, researchers must cut a circle in the skull and lift off the skull cap—which releases the pressure inside. Once that happens, the key evidence of swelling around the brainstem would disappear.

"The very process of the deaths and autopsies in Malawi obscured the finding," explains Taylor, a physician and professor at Michigan State University who spends half of every year treating and studying children with malaria at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Blantyre, Malawi.

Working with a group of ophthalmologists, Taylor identified changes in the retinas of some of the sick children that appear to correlate with evidence of cerebral malaria and no other discernible cause of death upon autopsy. Once they developed the new diagnostic standards that could be applied bedside (and did not require post-mortems), Taylor and her colleagues looked at 168 children who met their criteria between January 2009 and June 2011. While the children were being treated with quinine and other measures, the researchers periodically took images of their brains using MRIs.

The use of the MRI machine was also no small thing. Though MRIs are ubiquitous in the U.S., they are few and far between in many parts of Africa. Before 2008, before the study began, the nearest machine to the hospital in Blantyre was 1,000 miles away, making it impossible to observe what was happening in children's brains while they were still alive and compare the process in survivors to the one in those who died. GE Healthcare provided an MRI to the facility in 2008, according to a press release from the university.

Twenty-five of the 168 study participants ultimately died; of those, 21 (84 percent) had initial MRI scans that showed severe swelling of the brain. Among those children who eventually died and had a second MRI, all showed either the same swelling or showed the progression of swelling and pressure on the brainstem that Taylor and her colleagues had predicted. Meanwhile, of those who survived, only 27 percent had severe swelling at the start.

The survivors who initially showed swelling give the researchers hope, Taylor says, and are the impetus for a follow-up study the team is preparing. The idea is to mechanically ventilate the children who show severe swelling, with the hope that time will allow the process to reverse as it does in roughly a quarter of survivors. Ventilation would keep the children alive until they could breathe on their own.

At the same time, the researchers plan to explore four possible causes for the swelling itself. They'll look at two causes associated directly with the brain and two causes connected to the blood as they try to determine what exactly makes the brain swell in the first place and how it might be prevented.

"It's gut-wrenching when children die, but what keeps us going is that we are making progress against this Voldemort of parasites," Taylor is quoted as saying in the university's press release. "It's been an elusive quarry, but I think we have it cornered."

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that second MRI scans of children who eventually died due to cerebral malaria showed a progression of swelling in their brains. In fact, the second round of MRI scans showed either pregression of swelling, or the same amount of swelling shown in the first round od scans.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Stav is a general assignment staff writer for Newsweek. She received the Newswomen's Club of New York's 2016 Martha Coman Front ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.