Greece’s economy is on the brink of collapse after the capital controls imposed ahead of Sunday’s referendum left the country with shortages of food and drugs, the tourist industry facing a wave of cancellations and banks with barely enough money to survive the weekend.

Banks said they had a €1bn cash buffer to see them through the weekend – equal to just €90 (£64) a head for the 11 million-strong population – and would require immediate help from the European Central Bank on Monday whatever the result of the referendum, in which the two sides are running neck and neck.

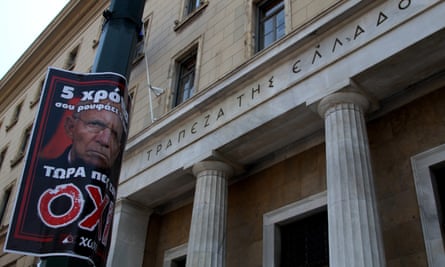

Alexis Tsipras, Greece’s prime minister, was fighting for his political life on Friday night, using a rally to say that a no vote would enable him to negotiate a reform-for-debt-relief deal with the country’s creditors.

The survival of the Syriza coalition, formed just over five months ago to repudiate five years of austerity programmes, was in doubt as Greece started to suffer shortages of basic provisions, including the sale of vital drugs in pharmacies nationwide.

Food staples, such as sugar and flour, were also fast running out on Friday as consumers started to feel the effect of the restrictions.

“We have shortages,” said Mary Papadopoulou, who runs a pharmacy in the picturesque district of Plaka beneath the ancient Acropolis. “We’ve run out of thyroxine [thyroid treatment] and unless things change dramatically we’ll be having a lot more shortages next week.”

Greek islands, where thousands of holidaymakers headed this week, have also been hit, with popular Cycladic destinations such as Mykonos and Santorini reporting shortages of basic foodstuffs. More than half of Greece’s food supplies – and the vast majority of pharmaceuticals – are imported, but with bank transfers now banned, companies are unable to pay suppliers.

Queues were reported at every cash machine in Athens on Friday night and business groups warned that the economic shutdown in the week since Tsipras called the referendum had already caused lasting damage to the economy.

“Imports, exports, factories, firms, transport – everything is frozen,” said Vasilis Korkidis, who heads the national Confederation of Hellenic Commerce. “The only sectors in demand are food and fuel.”

Korkidis said the economy had suffered losses worth €1.2bn in the past week and that the cost would have to be added to any fresh bailout deal. “Even in the best-case scenario, it is going to take months to recover from the shock of closed banks and capital controls,” Korkidis said. “Now that they are in place, capital controls may last for a year.”

Tourism, the mainstay of the Greek economy and its main export earner, has seen an estimated 50,000 holidaymakers cancelling bookings every day since Tsipras walked out of talks in Brussels a week ago. The Greek Tourism Confederation (SETE) announced that bookings were down by 40% in the past few days.

The ECB will meet on Monday to decide whether to step up its help to Greece under its emergency liquidity assistance scheme. The head of Greece’s banking association, Louka Katseli, told reporters: “Liquidity is assured until Monday, thereafter it will depend on the ECB decision.”

Despite rumours, the Greek government kept the daily limit on cash withdrawals at €60 (£42) on Friday, gambling that the banks would have just enough money to cope with demand until the referendum, which was ruled lawful by Greece’s top administrative court.

Analysts warned that the yes side – which would be prepared to accept the terms demanded by the European commission, the ECB and the International Monetary Fund – would comfortably win if the banks ran out of cash altogether. Yiannis Dragasakis, the government’s vice-president, said ATMs were fully supplied with cash before the weekend.

On Friday, Tsipras urged Greeks to give him the mandate to negotiate a better deal, saying that his argument was supported by an IMF study showing that his country’s debts were unsustainable even on the rosiest economic assumptions. “I urge you to say no to ultimatums, blackmail and fear. To say no to being divided,” Tsipras said. It has emerged that the eurozone tried to stop the IMF publishing its study.

Huge crowds – from young students to pensioners with grandchildren in tow – packed Athens’ Syntagma square, jamming the nearby metro station and surrounding streets to hear Tsipras address a mammoth no rally on Friday night.

“I’m here to shout no at the top of my voice,” said Panos Stathopoulos, a recently retired dentist. “No to austerity; no to this European Union that seems to have no sentiment, nothing.”

Sporting a red-and-white OXI sticker, Stathopoulos said that after five years of austerity, “They know the situation very well, and still they keep trying to impose these measures on the weakest of us – I’m sorry for the founding fathers of the EU, I don’t think they ever envisaged a Europe like this.”

Friends and colleagues Eri, Constantina and Marta – all psychologists – said they had come because “we want to have hope.” They would vote no on Sunday because “we want to be able to express our own opinions, and to decide for ourselves, in our own country,” said Eri.

The yes campaign turned the centre of the open-air – and open-ended – Panathenaic Stadium in central Athens into a sea of Greek flags dotted with some EU ones. They also spilled out for about 50 yards down the avenue that runs across the stadium’s open side.

It was an altogether more rumbustious – and better-attended – demonstration than the one on Tuesday in Syntagma Square, which was marred by rain.

On Friday night, toting a big EU flag, Dimitris Tsaoussis, a financial analyst, said he was there to “tell my European family that we belong in Europe and we will stay in Europe”. Zacharias Sachinis, a marketing manager with a chemicals firms, who was at the rally with his wife and son, said he was going to vote yes on Sunday because “the euro is good for Greece”, even though he didn’t like “the dictatorship of Schauble.”

As on Tuesday, the atmosphere was good-natured. But below the surface calm there is deep concern – and some trepidation. With the approach of the referendum, growing numbers of Greeks are becoming reluctant to give their names to reporters.

“I came because we can’t be indifferent,” said one young woman emphatically. But she balked at identifying herself. So did her friend, who said: “We can’t predict the consequences of anything. That’s why we’re nervous.”

Polls have tightened in recent days following warnings from the commission and Greece’s eurozone partners that a no vote would mean its exit from the single currency. Support for the yes side is coming primarily from voters over 55, with all other age groups backing Tsipras.

An already tense atmosphere was heightened on Friday after it emerged that the country’s defence minister had said that the military could ensure internal security if necessary.

Greece’s post-war history of military dictatorship meant Panos Kammenos, who also heads the nationalist, rightwing Independent Greeks party, caused controversy when he said: “The country’s armed forces guarantee stability internally, the national sovereignty and the country’s territorial integrity [and] stability in relation with the country’s alliances.”

Vicky Pryce, the Greek-born chief economic adviser at the Centre for Economics and Business Research, said: “There has been too much austerity, but a no vote would make things worse. It would almost certainly mean banks becoming insolvent, an exit from the euro and a much faster decline in economic activity with hyperinflation following as the drachma that is introduced instantly devalues.

“A yes vote would keep banks open and give a mandate for a deal to be struck that recognises the new Greek realities and includes, as the IMF now says, restructuring of the debt which every economist knows is unsustainable. This would offer some light at the end of the tunnel. A no vote would make that almost impossible to accomplish and could plunge Greece into years of economic turmoil.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion