A five-minute taxi ride from central Calais, past the seafront restaurants serving moules and chips to tourists, past the Majestic wine cash and carry, and just beyond the neat back gardens at the edge of the town, suddenly there is a devastating vision of Europe’s refugee crisis. One minute, you are driving through placid suburbia; the next minute, you are deposited at the entrance to a sprawling shantytown, where conditions appear worse than in the slums of Mumbai, a camp that is now home to more than 6,000 people, many of them vulnerable and unwell.

In the wasteland behind the red-roofed houses, the unofficial family section of the camp sprang up in October. First there were a couple of tents, then a few shacks thrown up by charity workers, made from cheap wood with plastic sheets tacked on to them. Now, a few weeks later, there are more than 50 huts and tents, home to families from Iraq, Iran and Syria, with dozens of children playing in the mud.

Unfortunately, in the rush to accommodate the hundreds of families who have arrived in the past month, tents were put up in an unoccupied area of sandy wasteland previously used as an informal toilet by several thousand people. “Many of the children are suffering from infections now,” François Guennoc, a coordinator with the main local charity, L’auberge des Migrants, notes wearily, supervising as volunteers bang together wooden huts so families can be moved out of sagging tents. They can’t build them fast enough to accommodate the flow of new arrivals.

The population of this camp, known locally as the New Jungle, has doubled in the space of a month, and quadrupled from around 1,500 in early summer. “Every day in September and October between 100 and 150 people arrived, and we gave out that number of tents,” Guennoc says, but the figures are an estimate because no one is counting. There is no UN or Red Cross presence; no one is in charge. The French state accommodates about 200 women and children in a converted holiday centre on the edge of the camp but there are too many now to fit in the centre, so families live where they can. “It is the largest slum in Europe and probably the worst,” Guennoc says.

Karzan, 35, an Iraqi nurse, is living at the heart of it, in a wooden structure, half the size of a small garden shed, with his wife Sharmin, his one-and-a-half-year-old son Hemn and his brother-in-law. “When I came here a month ago, there were two families. Now there are 40, 50 or 60. We have never lived like this before. We feel like we are dying slowly.”

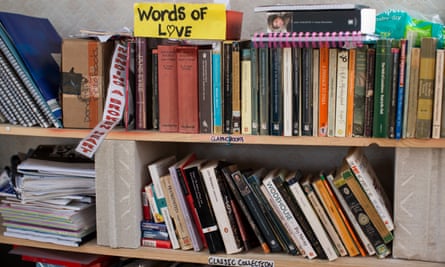

In the past month the camp has become denser; previously, tents were huddled together according to the geographical origin of the people living there – Sudan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Ethiopia, Eritrea. Now the sections have melded into one huge mass. In the absence of help from the state, people are helping themselves. The noise of hammering is everywhere, as refugees knock up basic wooden frames that become, in the space of a day, restaurants and shops, hairdressers and phone-charging booths, arranged along an informal high street. Volunteers from across Europe have built a school, a day-care centre for children, a library, a couple of mosques, a church, a refugee advice centre, an art therapy tent and medical centres.

But none of this does much to detract from the squalor and misery of the camp. There is rubbish everywhere, discarded sleeping bags, rotting food, broken shoes half buried in the sand. Small cooking fires are burning all over the place, stoked with torn-up plastic sheeting, creating acrid smoke. On Saturday night, a gas canister exploded, and several huts were burned to the ground.

Because of a surge of clothing donations, people appear well-dressed until you look at their feet, where a hierarchy of good fortune is instantly visible: the people with broken flip-flops at the bottom, followed by those wearing socks under flip-flops; luckier are the people with strong shoes, which are worn as slippers with the back pressed down because they don’t fit properly; only the most fortunate have boots or trainers of approximately the right size.

In the past two weeks, a new chunk of funding for policing the area has been released, so residents are getting used to the sight of riot police in full body armour walking slowly through the camp in a pack of 16 or 18, loosely two by two, some armed with guns and truncheons, some of them wearing paper masks, as if the air here is particularly noxious to them. These are not friendly community officers; they don’t engage in eye contact, and they don’t look as if they are here to offer humanitarian assistance to the camp’s residents. Later, they return wearing boot protectors, as though they have entered a contaminated zone.

It is a strange vision in the middle of a camp that seems relatively peaceful. “Who could be scared of police who are too scared to get their boots dirty?” a Liverpudlian, ex-army volunteer wonders, as he distributes aid funded by the Bradford-based Human Relief Foundation.

In the family field, the late autumn sun is cold and there’s a sharp wind from the sea. Two weeks ago, many of the children were vomiting and had diarrhoea; today, they are cheerfully kicking a football around in the small clearing in front of the tents. The adults’ mood has not lifted. When it rains, water comes through the plastic roof of Karzan’s hut, soaking the pillows and the blankets; every night, the baby wakes, cold. They sleep on a wooden pallet with a blanket draped over it. There is no electricity; water has to be fetched from one of three water points in the camp and wheeled across the muddy scrubland in watering cans and oil canisters piled into old Lidl shopping trolleys, so Hemn has had only two (cold) baths in the space of a month.

Until this summer, Karzan had no desire to leave his home in Kirkuk, or his well-paid job in the hospital where he has worked for the past nine years. He was forced to flee two months ago, when Daesh (Isis) told him that if he didn’t agree to work as a nurse for their fighters, they would kill him. He paid a people smuggler $10,000 to get the family by train and car to Calais, but now there is no more money, so they are stuck here. He is somewhat buoyed by an ill-founded conviction that change may be imminent in the UK’s policy towards refugees in Calais. “I don’t want to be an illegal immigrant. I want to come and work as a nurse. I am waiting for the government of England to take me.”

In any case, the family has no choice but to wait. With the baby, they can’t join the hundreds of people who leave the camps in small groups of four or five every night to try to get through the layers of metal fencing that separate them from the Eurotunnel tracks, or to find a spot hidden in the undercarriage of an articulated truck or on the roof of a lorry. The people smugglers who help people find lorries to climb into charge much higher rates for families because transporting children is much riskier; it’s hard to stop a baby from crying, increasing the chance that the driver will hear the noise, stop the truck and remove them.

Karzan and his wife are embarrassed to be relying on food parcels, but are grateful for the help – except, they concede, when the handouts contain old supermarket salmon pieces, two days past the sell-by date, as they did this morning. Karzan is surprised that his family has been offered no help by French medical or welfare officials. “No one has come,” he says, expressing polite surprise that this is how European countries treat refugees. “We are humans, not animals.”

“What if David Cameron’s baby was living like this? There is no difference between this baby and an English baby,” Sharmin says, breaking off from cooking bread on a fire, (which is disconcertingly close to the plastic sheeting by the hut door) to stop her wriggling son from walking with muddy feet into the neighbouring tent, where another Iraqi woman is trying to feed her three children.

The knowledge that trying to get through the tunnel is harder with a baby means pregnant women, such as Hawir, 24, also from Kirkuk, are trying to penetrate the fences with added determination. For a while, she and her husband Hawraz, 22, from Mosul, were in the relatively privileged position of owning a pair of wire cutters, bought for €35 from another camp resident who had purchased them in a Calais hardware store, but these got lost when they had to run from the police. They have been in the camp for a month and have made five night-time attempts to get themselves to the train track, to jump on a train.

“It’s very dangerous, but what are we going to do? We can’t live like this. There are more and more tents, more and more people. We have to try; she wants to keep trying,” Hawraz says.

Everyone knows the risks involved. At least 20 people have died since June, according to Doctors of the World, which is the only organisation collating this information, although this is likely to be an underestimate, because they are not always informed by police. Of these, eight were run over by cars, lorries or freight trains, two people drowned trying to swim to Britain, one was electrocuted on the train tracks, six people were found dead in the tunnel, and one was found dead in a lorry (probably crushed by cargo pallets).

Hawraz speaks some English because he lived in Britain for a year in 2012. Last time, he got there tucked in the undercarriage of a lorry, but he had to return to Iraq before his asylum claim was processed because his parents died, and he needed to look after his younger sisters, who he has subsequently settled in a refugee camp in Turkey. In 2012, there were just a few hundred people living in tents in Calais. He is overwhelmed by the change. “So many tents, so many nations. People shouting and fighting. It is very, very dirty.”

Hawir, an Iraqi Kurd, was born when her parents were making a similar journey, fleeing Saddam Hussein, and seeking sanctuary in Iran. “I don’t want my baby to be born here. It should be born in a good place,” she says.

The couple have very little grasp of the UK’s rigid stance on refugees and are looking for reassurance that they will soon be welcomed. “Do you have any news for us? Do the people of England want to take us? What about Northern Ireland? What about Scotland? Wales? Will they take us?” Hawraz asks.

Away from the family section of the camp, the day begins more slowly; the nightly procession to the train tracks requires hours of walking through woods and back roads, to avoid the police, and most residents are exhausted. Along with gloves, cigarettes and ear-warmers, all the shops have high-caffeine drinks displayed prominently on their shelves – Red Bull and Monster are particularly popular. “All night they are running for the trains. When they come back in the morning they need that energy,” an Afghan shopkeeper explains, asking for his name not to be published because he says the police have caused him endless problems by repeatedly asking him to produce a licence to run the shop, which, naturally, he does not have. He is annoyed by the police’s attitude, pointing out that without the shops, all 6,000 people here would have to walk a 2km round trip to the nearest supermarket in Calais. Most residents have some money but he gives eggs and bread to those he can see have none.

By 10 o’clock, a crowd has gathered outside the medical centre run by Doctors of the World, the only large charity to have been stationed long-term in Calais. The range of patients’ problems reflects the state of the camp – respiratory infections from the cold; stomach infections from the water (which a recent analysis revealed to be infected with E coli); scabies from living in overcrowded tents, with nowhere to wash clothes and bedding; hand lacerations from the barbed wire; limb fractures from falling off lorries or being pulled by police from a train (a lot of people in the camp are on crutches); blisters from long walks through Europe in ill-fitting shoes; psychological problems from the untold strain of leaving home and families in wartorn regions, and trailing through Europe for months in profoundly dangerous and stressful conditions.

Hakim, a 27-year-old from Eritrea, wants a doctor to look at his knee, which is swollen, injured when he was pushed from a train by police two nights ago. He has been in Calais for three months; for two months, he has been making nightly attempts to cross through the tunnel; one month, he spent in a French detention centre (he is not sure why).

He is treated in a garden shed, with no running water, a shower curtain hammered above the door for privacy, alongside Adam, 25, from Sudan, who is in great pain, having an abscess drained by French nurse Catherine Olivier, who apologises for the facility’s basic appearance. Elena Parker, a Russian-born nurse who until recently worked at the London Clinic on Harley Street, says she is familiar with the injuries from the field medical training she received in Russia. “Where in normal life do you see barbed wire injuries?” Her colleague, Dr Jean-François Patry, is depressed at having to treat patients who have been beaten by lorry drivers and the police, and despairing about the conditions in which the camp’s residents are living. “They are here because there is war in their own countries. France and Britain should be more welcoming.”

Over the course of the day, the clinic treats more than 75 people, ferrying one woman in the early stages of labour to the local hospital. Chloe Jones, a volunteer from the UK, helps run an overflow clinic from a caravan opposite, and spends most of the day handing out cream for scabies infections. “We see people who have been hit on the head and on the shoulders with police batons, people who have been kicked to the ground, people with achy legs from walking so much, blisters from ill-fitting shoes,” she says.

On Saturdays, dozens of volunteers, mainly from the UK, arrive at the camp, bringing donations collected by local schools and faith groups. Several refugees are wearing Dismaland T-shirts after Banksy’s Weston-super-Mare installation closed and shipped its timber and fixtures to Calais. Some people drive up and start distributing packets of ginger nuts from the back of their car; a few are accompanied by children on half-term. The permanent community of volunteers are uneasy at a phenomenon they describe as “voluntourism”, and are frustrated by people who come with cars filled with teddies and baby clothes (since 90% of the people here are young men), but most of the donations are welcome.

The well-informed donors know to drive to a warehouse run by L’auberge des Migrants, with help from smaller groups such as Calaid and Help Calais. This Saturday, 22 vans arrive from the UK and deposit deliveries in the warehouse for sorting, before being packed with a more carefully selected, themed distribution to take to the camp. One team takes out food parcels, with rice, oil, chickpeas, tomatoes and sugar; another takes out firewood; there is a toiletries distribution, and medical equipment is sent to the first aid camps.

Inside the warehouse, where a huge quantity of unsorted boxes is piled high, volunteers sort through the donations. A satin wedding-dress, with pink roses sewn on to its train, is pinned to the wall as an example of the kind of donations that are not welcome. Mostly they need trainers and walking boots (particularly sizes 41 and 42 – 7 and 8 in UK sizes), sleeping bags, and small men’s trousers (waist sizes 26-32). (They have no use for the bigger ones they get from the UK, because “there aren’t a lot of fat people in the camp”, one of the sorters says.)

Jennifer Wilson, a teacher from Harare who has been volunteering for more than a month, is sorting through the clothes, discarding useless fake fox scarves and ripped, dirty castoffs. During the week she has been teaching English in a new schoolroom on site. “In my class I’ve had doctors, teachers, engineers and architects. They are educated people. I would like people to know that, that they are not just coming to milk the state,” she says.

James Fisher, co-founder of Calaid, set up on Facebook in August, has just driven with about 1,000 secondhand sleeping bags and about 200 tents from a warehouse in Slough. He is struck by how much the camp has changed since the summer. “The land it covers seems to have increased by 30%. There’s no official structure, no camp leadership, just a group of people surviving, a random collection of humanity camped in a field,” he says. The volunteers’ presence has helped improve conditions. “It is unregulated, it is a little bit chaotic, but it is positive.”

Some of the newer British volunteers are cheerful as they hand out supplies. “It’s touching, isn’t it?” they say, brightly. “The humanity is amazing!” Their glowing enthusiasm is at odds with the muted resignation of the people waiting patiently in line for handouts. Only the newer arrivals, such as Dirik, an 18-year-old mechanical engineering student from Syria, look optimistic. He has only been here for 24 hours and talks happily as he waits in line for food about his desire to bring his skills to Britain. The other men, who have been here longer, have a more deadened expression in their eyes. Most are aware that the increased French police presence has made it harder to breach the border and their chances of getting to the UK are vanishingly small. They know they are powerless, stuck indefinitely in this muddy bottleneck.

Labied Razzaq, retired from running a software business, has driven from Northampton with 105 pairs of shoes in a roof box, and is giving them to people wearing flimsy flip-flops. He came to the UK from Iraq when he was 16 on a scholarship, and is struck by how many similarly studious young men he has met in the distribution queues. “Doctors, pharmacists, engineers. Don’t we need these people?” he asks.

A Danish volunteer (who gave only his first name, Aske), volunteering in a tent where nursery-aged children are doing hand painting, is dismayed that no state help has materialised for the growing number of children. He is disturbed to see boys of 12 and 13 with scars they have picked up when trying to jump on the trains. “We do what we can, but the government could do a lot more for them. We’re not getting any help. The camp is not a good place for children,” he says. “It’s very depressing to see a lot of well-educated, smart people stuck here. This could be us if a crisis happened in our countries. It is depressing to see these people lose hope.”

Abdarahim, 21, has lost most of his. He fled the war in Sudan two years ago, and has spent four months here, trying nightly to reach the UK. He is mourning his friend, Mohammad Ibrahim, who was on the train tracks this summer, as they tried to get to England. “He was too close to the train,” he says, talking inside the relative peace of the Jungle library, a new, clean and well-stocked building. He is not sure if Mohammad’s surviving family at home know that he is dead. “His parents were dead. He was responsible for his younger brothers and sisters. He was a very generous, very kind man. I feel really bad about him.”

The volunteer librarian Arash, a 23-year-old computer engineer and interpreter from Mazar-i-Sharif in Afghanistan, is tidying the shelves, lining up Sherlock Holmes stories alongside Anna Karenina and Our Man in Havana. He looks exhausted and despondent; this morning, his mobile phone has been stolen, severing communication with relatives at home. “It is good to come here for a few hours, to change your mindset; it lifts the pressure,” he says. “It isn’t easy living here. Every night you are afraid that you will break your leg. I’m tired of running from the police.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion