Story highlights

Invasive species cause over $100 billion damage each year in the U.S.

Invasivores are hunting and eating them to protect native species and ecosystems

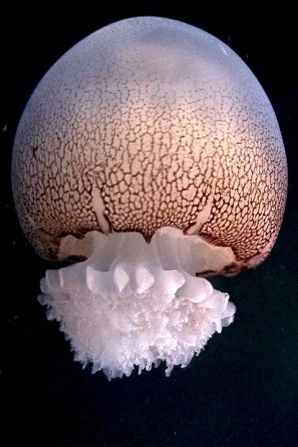

When the marine invasion started, the U.S. was taken by surprise – and overrun.

Today, the lionfish enjoys virtually unrivaled supremacy in its ever-expanding territory from the East Coast to the Caribbean. The distinctively striped interloper from the Pacific has few predators willing to face its venomous spines, and a devastating appetite.

Lionfish can reduce native species populations by 90% within weeks of arrival, decimating many useful species such as fish that feed on coral-damaging algae. They consume enough to become obese, and even resort to cannibalism.

These voracious predators are spreading rapidly – female lionfish release two million eggs a year – leaving conservationists with an uphill struggle to contain their numbers and preserve threatened ecosystems.

Taking the fight to the dinner table

In Florida, where lionfish have massively disrupted the fishing industry, locals are fighting back by eating them.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has led a campaign to put lionfish on menus, encouraging fishermen and traders to participate. Environmental group Reef organizes lionfish derbies to catch as many as possible, and has released a lionfish recipe book.

Dozens of local restaurants have begun serving the new arrival in the form of ceviche and sushi among other dishes, although demand has yet to match supply.

Conservation biologist Joe Roman believes this approach can make a difference.

“We have seen some impact and evidence of populations declining,” says Roman, citing the example of Cuba where the government have encouraged the harvesting of lionfish.

Since 2003, Roman has helped to pioneer the “invasivore” movement through his popular website ‘Eat the invaders,’ offering information and recipes to help offset the disastrous impact of invasive species.

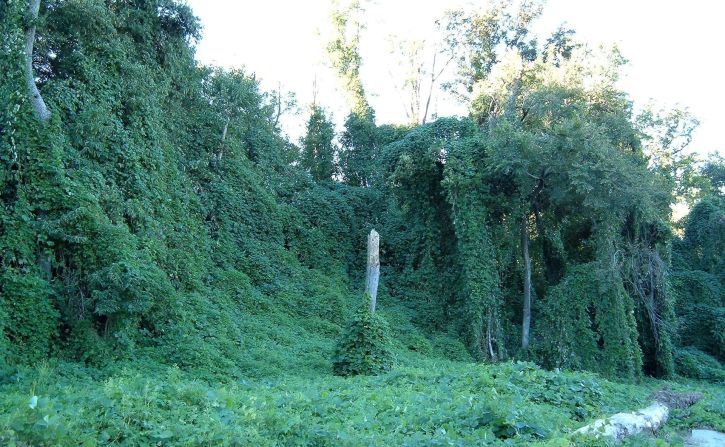

From feral pigs rampaging across Texas, to the Burmese Python making itself at home in Florida, invasive species cost the U.S. over $120 billion a year in damage, wiping out local species and destroying ecosystems.

Conservation with an edge

Roman does not believe that eating alone can solve the problem, but sees it as a valuable – and enjoyable – access point.

“I spent my career trying to control people’s appetites, to manage native species so we don’t deplete them,” the conservationist says. “Here is a case where voracious appetites do the environment a favor. You want it to not be a chore, to be fun, and tasty!”

The invasivore movement has benefited from the growing popularity of sustainability lifestyles, and its offshoots such as foraging, as well as reaching out to hunters that would usually be on the opposing side.

“There is an overlap,” says Roman. “We have more conservationists going out to harvest their own meals, and hunters focusing on (killing) species that will improve the environment.”

The main value may be in awareness, believes Dr. Matthew Barnes, an ecologist at Texas Tech University, who maintains online resource Invasivore.org

“I’m very hopeful about eating as an educational tool,” says Barnes. “Campaigns like ‘clean, drain and dry’ between lakes have been effective in making people aware of moving zebra mussels and exotic plants.”

Invasive species are typically introduced by human movement, which must be the focus, says Barnes.

“We know that the earlier in the pathway you try to manage them, the more effective the results. It’s much cheaper to prevent introduction than deal with a species once it is established.”

The Invasivore blog stresses the need for safety. Species near roads can accumulate toxic metals, and the Florida pythons were found to contain double the safe level of mercury.

But if foragers are careful, Barnes believes the practice can be accessible to all, particularly if they start with invasive plants.

“We always say that dandelions are a good gateway invasive,” says the ecologist.

A global response

Dr. Piero Genovesi, chair of the Invasive Species Specialist Group at the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), is concerned that the damage is growing steadily worse.

“The problem is increasing everywhere,” says Genovesi, pointing to invasive growth in the Mediterranean Sea, and the spread of the water hyacinth through Africa – attracting malarial mosquitoes – as leading concerns.

Encouraging human consumption can be useful, but carries its own risks, the conservationist says.

“We have to consider the possibility to use them as a resource – in some cases creating consumption can help to control populations,” says Genovesi. “But it could also create an interest to spread the species further.”

He adds that eradication has proved impossible in most cases, with rare exception such as feral cats in regions of Australia, but that eating invasives is less harmful than mass poisoning attempts that also kill native species.

Genovesi’s priority is to achieve consensus between regulators and industry to thwart invasions in advance, with early warning signals and rapid response measures to fall back on.

The EU recently announced control measures for 37 species, including the Sacred Ibis and North American Bullfrog. Genovesi welcomes the step but hopes for a larger-scale response as thousands of species are causing damage.

Maintaining pressure on the decision-makers is critical now, which means keeping the profile of invasive species high.

For invasivores, the challenge is to make their recipes irresistible.