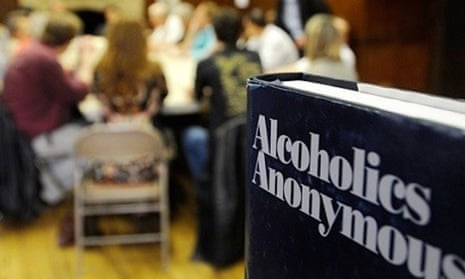

The Almighty plays a central part in the hallowed 12 steps of Alcoholics Anonymous. Six of them make reference to God, Him or Power. In one step, members vow to hand “our will and our lives” to God while another implores Him to remove their shortcomings.

Now the organisation’s religious undertone – and its utility in fighting alcoholism – has come under fire in Canada, where an atheist has lodged a human rights complaint alleging AA discriminated against him.

For more than two years, Lawrence Knight has watched his complaint snake through the Ontario Human Rights Tribunal. Earlier this year, the tribunal said the complaint raised a number of complex legal issues and recommended it go to a full hearing.

More than 23 years sober, Knight says he always found that the world of AA was an uneasy fit. “I come from a long line of humanists,” said the 59-year-old.

We Agnostics, a Toronto secular AA group created in 2010, seemed the perfect solution, offering all the support and companionship of AA but without the trappings of God. Here the 12 steps were still followed – each carefully rewritten to scrub out any mention of God or prayer.

But the group’s separation of church and sobriety didn’t sit well with some. In 2011, We Agnostics and Toronto’s other secular AA group, Beyond Belief, were delisted from the Toronto AA website and directory, in effect removing them from the city’s network of 500 weekly meetings.

The decision prompted tears and shock among the three dozen or so people who had embraced the secular groups. “It was painful. It’s shunning,” said Knight. “It was unbelievable that an organisation that can’t kick anybody out, and that prides itself on that, had kicked us out.”

Members of the secular groups – worried that their hard-won efforts at staying sober were now in jeopardy – vowed to push forward. What emerged was a parallel system of sorts, one that has today swelled to about 350 members in 12 secular AA groups across Toronto.

As the secular movement grew in numbers, Knight and others continued to push to be brought back into Toronto’s AA fold. They appealed to the city’s coordinating body, urging them to reconsider the decision. “We ran into a brick wall,” said Knight.

Frustration drove him to lodge a human rights complaint two years ago, claiming that AA had discriminated against his group on the basis of creed. While directed at Toronto’s coordinating body, the complaint also names the highest levels of the organisation in North America. “They didn’t make any decisions directly,” said Knight. “But there is something that they did do, in my opinion, and that is the fact that there have been agnostic meetings for 40 years, but they haven’t clarified anything; they didn’t have any human rights protocols in place.”

The result is a scattered approach to secularism around the world. In some places, such as New York City, secular groups are allowed to operate freely and under the umbrella of the local AA hierarchy. Other secular groups – from Des Moines to Vancouver – have been treated similarly to those in Toronto, pushed out and left to their own devices over their rejection of God.

Knight’s complaint will head to mediation in the coming weeks. To date, AA has argued to the tribunal that it is a special interest organisation, a status that affords it the right to restrict its membership.

The dispute hints at a broader question being asked among the group’s two million members worldwide as they seek to incorporate 12 steps first penned in the 1930s into modern times: How important is God and religion in AA’s quest to empower people to fight alcoholism?

Some, like Knight, argue that AA’s curative power lies not in religion, but instead in the fellowship it fosters. A growing body of research, he pointed out, now suggests that the roots of addiction are tangled in isolation and loneliness.

The argument clashes with the Toronto coordinating body, which has argued to the tribunal that a belief in the higher power of God is a bona fide requirement for groups in Toronto.

Officials in Toronto declined to comment, while a spokesperson from AA World Services in New York City said the organisation was unable to comment as the matter was before the Human Rights Tribunal.

Knight is hoping that the human rights complaint will force the organisation to definitively address the long-simmering issue. “Alcoholism kills more people than it saves. It’s killed a lot of my friends, it’s killed a lot of my family, it’s an insidious thing. And the best support system in the world is AA.”

But the strength of that support hinges on AA being accessible to all. “The point is that anybody should be able to go to a meeting and not feel intimidated, not feel forced out or that they have to believe in something that somebody else believes,” he said. “Because that’s just ludicrous in this day and age.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion