For once the weather forecasters were wrong about bad news.

The entire staff of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, all the passionate amateur astronomers of the Flamsteed Society, and many anxious members of the public, spent the weekend obsessively refreshing the Met Office weather forecast app – but the threat never changed, the skies over London would have 100% cloud cover, and the best chance of observing the transit of Mercury before 2049 would be lost.

When the Observatory’s many clocks struck noon, and the skies overhead were still an improbable Mediterranean blue, the elation was tangible.

“Every time we have a big event over London, we expect the weather to turn on us,” astronomer Tom Kerss said. High over his head, light too dazzling to look at was pouring through the slot in the dome through which the Great Equatorial Telescope peered, trained on the sun after almost a century of looking at the moon and stars.

The telescope, one of the largest in the world when it was built in 1893, been fitted with a filter the size of a bin lid for the occasion. “Without it,” Kerss said, with a certain grim satisfaction, “anyone looking through it straight at the sun would have their retina burned out and go permanently blind – straight away. We have been warning and warning people against looking at the sun through telescopes.”

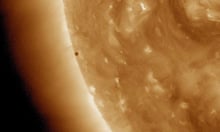

“Wow! I can see it clear as day – that’s Mercury! It’s happening!” said Roman Gerasimon, who up to that point had been calmly explaining the hard science of the phenomenon to a group of schoolchildren, but was now losing it as a jet black dot appeared on the blood red disc of the sun in the eyepiece of his telescope. The filters gave the transit a truly prog-rock colour scheme, missed by Edmund Halley, when he first observed it in 1677.

A steady trickle of planet watchers had been making their way up the steep slopes of the hill for hours. Hardened by long freezing nights waiting for clouds to part to reveal even a single star, they were easily distinguished from the frivolously dressed dog walkers and joggers: they had hats and water bottles, thermos flasks and jumpers tied around their waists. Many were clanking with kit, even though the observatory had supplied an array of devices for the public, from startlingly effective French-made cardboard box viewers, to staff astronomer Greg Smye-Rumsby’s own precious Questar telescope: “the Rolls Royce of telescopes”, he said, that “goes with me everywhere.”

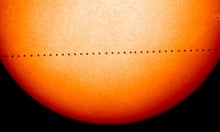

By 1pm the black dot was visibly moving across the blazing face of the sun, visible in the cardboard box, on tablets linked to cameras and telescopes, and streamed live from the eye of the Great Equatorial. Detachment was abandoned by scientists and visitors alike, movingly aware that they were comrades under the sky with millions of others across the world and centuries of observers before them.

“You are witnessing the poetry of the heavens in motion,” astronomer Marek Kukula said, “as a rock the size of Africa flies past the sun.”

Similar scenes played out around the world, or at least in those countries where the transit occurred in day time. Telescopes erected at the Birla Planetarium in Chennai, India, displayed Mercury on a screen, from which passersby snapped pictures of the alien world in motion. In Germany, amateur astronomers peered up at the spectacle through telescopes set up in the grounds of the Bergedorf observatory in Hamburg.

That Mercury is small for a planet, only a smidgeon larger than the moon, and 48m miles away did not matter. “It was great: we had a gorgeous day for it, much better than we’d expected,” said David Rothery, who explained the transit to schoolchildren while observing from Mulberry Lawn park at the Open University in Milton Keynes.

Jim Green, director of planetary science at Nasa, said that while surface temperatures on the solar system’s innermost planet reach more than 400C, craters that pock the planet’s north pole provide some respite from the heat, with regions that are permanently in shadow. “We believe there is water and other volatiles in these permanently shadowed craters,” he said.

From its vantage point far above Earth, the US space agency’s Solar Dynamics Observatory watched Mercury make first contact at the edge of the sun and then work its way steadily across the dazzling yellow disc until it emerged on the other side.

All the while, Nasa scientists monitored the transit it the hope of learning about the extremely thin cloud of gas, the “exosphere”, that surrounds Mercury and stretches out like a comet’s tail for hundreds of thousands of miles.

“It’s a once in a lifetime experience,” Helen Bennett said at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. “I’ve been talking to all my friends about it, and trying to persuade them to come too.”

Eddie Yeadon, a retired physicist and founder member of the Flamsteed Society, said spending cold nights looking up at the moon held no thrills for him any longer. “But to see something as rare as this actually happening – that’s a heart stopping moment.”

“Our world is just a speck of dust, and our sun a pathetic little thing,” said amateur astronomer Rupert Smith. “Maybe if people looked up more they would realise how absurd all their fighting over grubby little scraps of land is.”

Bennett had to leave the queue to collect her children from school, and by the time she came back it was all over.

The long threatened cloud cover began to roll across the brilliant heavens. The inside of the magical cardboard box viewer just looked like a cardboard box again. People began to drift away.

“Ah well,” Kukula said. “It was glorious while it lasted.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion