At 2:30 on March 2, 1959, the 32-year-old trumpet player and bandleader Miles Davis took six sidemen into a New York City studio, where they spent the afternoon and early evening recording three songs. On April 22, the same cohort, minus one of the two piano players who worked on the first date, returned to the same studio and recorded two more songs. As far as the musicians were concerned, that was the end of the story. For the rest of the world, it was just beginning. Four months later, the five selections were released on the album "Kind of Blue." The record became an immediate success, embraced by jazz fans, critics and musicians. Two songs on the album, "So What" and "All Blues," quickly became staples in the jazz repertoire. "So What" even became a favorite of college and high-school marching bands. Meanwhile, the record kept selling, and selling and selling. Today, 50 years after it was released, "Kind of Blue" remains the bestselling jazz album of all time. More than 4 million copies have been sold, and the album still sells an average of 5,000 copies a week. If you have a jazz album on your shelf, odds are it's "Kind of Blue."

Why this album? Out of the thousands of jazz albums ever recorded, why does "Kind of Blue" maintain its hold on our imaginations more than any other? The simplest response is to say, because it's beautiful. You won't find many recordings that boast more thoughtful compositions or performances of any higher caliber than the solos and ensemble work of Davis, John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb. The music has no weak spots. Or perhaps it's the unthreatening nature of the music: five medium-tempo selections, all played at the level of human conversation. There's nothing in these songs that would scare anyone. On the other hand, there are none of the signposts or road maps that make jazz accessible to listeners—no standards that you can hum, no vocals. And yet, even when you hear this album for the first time, it's like meeting an old friend. It sounds familiar somehow. Even today, at 50, "Kind of Blue" sounds, as Quincy Jones puts it, "like it was made yesterday."

Old yet new, strange but familiar—how can music possess such contrary qualities and still sound coherent? In the case of this album, it's because the music was designed that way. It coheres because it was conceived as a whole. Each cut contributes to the whole (in this sense, it might better be titled "Kinds of Blue"). One of the most important elements built in from the start was an open-ended sense of discovery and exploration. The men who performed on the two recording dates knew almost nothing about the music they would play before they entered the studio. As Bill Evans, the principal piano player on both recording dates, wrote in his liner notes for the album, "Miles conceived these settings only hours before the recording dates and arrived with sketches which indicated to the group what was to be played. Therefore, you will hear something close to pure spontaneity in these performances."

Davis's sketches, at least a couple of them collaborations with Evans, are more like themes or motifs than fleshed-out songs. But this was the beauty of the challenge: the score demanded a lot of the players that day, because it left so much space for a soloist to fill. The musicians responded by giving the space between the notes the same weight they gave what is played. Their silences really are golden. Listening to these performances is to be reminded of Robert Frost's dictum about the making of a great poem: "No surprise in the writer, no surprise in the reader."

You don't have to know any music theory to appreciate this music, but understanding the context in which it was created does help clarify what Davis was trying to do. Since the '40s, jazz had been dominated by bebop and then hard bop, music characterized by frenetic tempos and chord changes stacked upon chord changes. It required deep musical sophistication to play that style, but while Davis had the chops for bop—had indeed been one of its prime movers—he had lost his enthusiasm. "I think a movement in jazz is beginning away from the conventional string of chords," he told an interviewer six months before the recording of this album. "There will be fewer chords but infinite possibilities as to what to do with them. Classical composers—some of them—have been writing this way for years, but jazz musicians seldom have." So he deliberately went another way with "Kind of Blue," supplying the barest hint of a song in each case, giving his musicians the scale or scales upon which to improvise and then turning them loose to create their own melodies and variations. It was a return to and an exaltation of lyricism.

"Kind of Blue" draws on the two essential tributaries of jazz—improvisation and the blues—to create music full of space and possibility, certainly music that appealed to players and listeners alike.

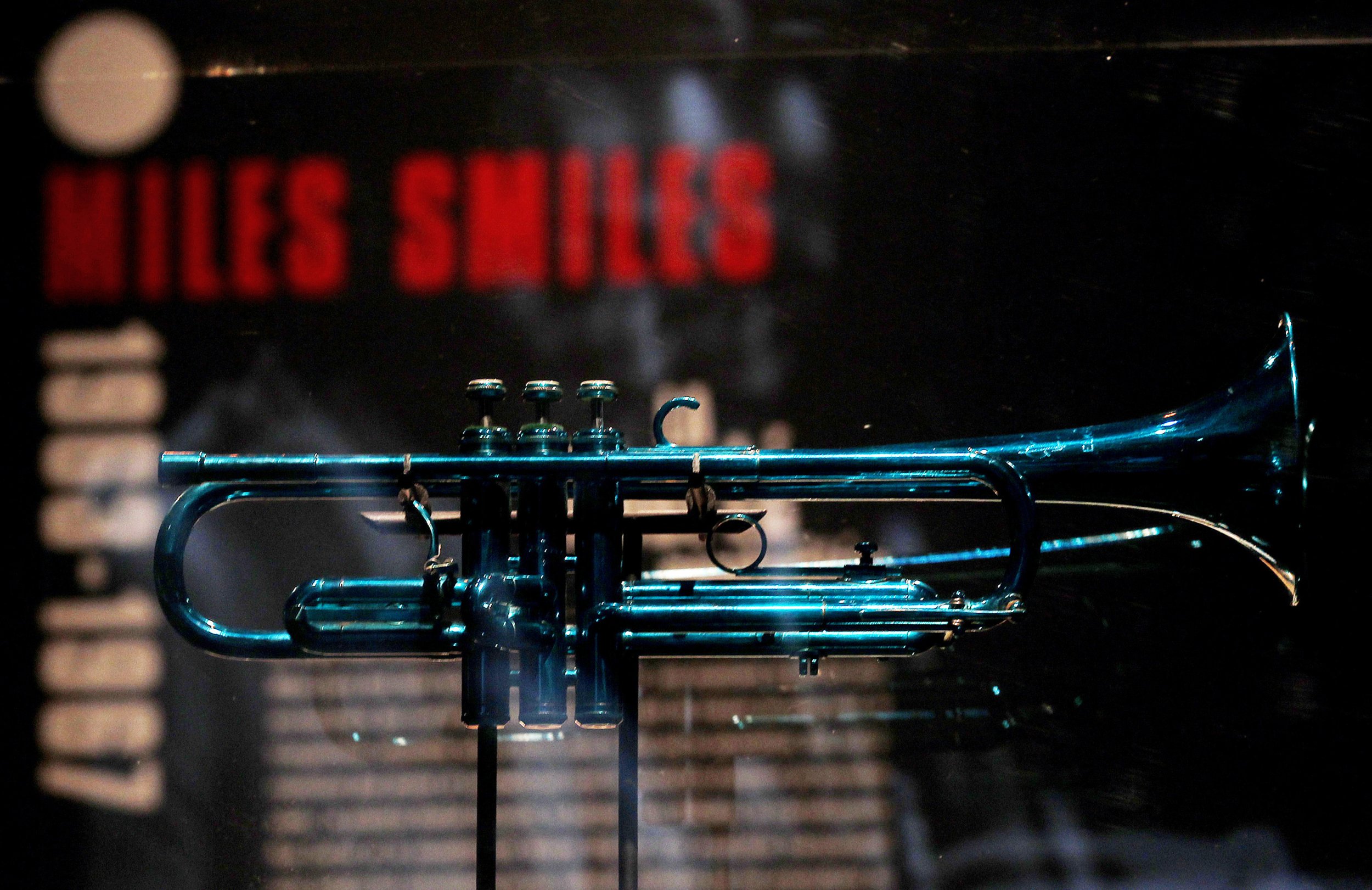

Critics have never stopped writing about "Kind of Blue," and Ashley Kahn's absorbing 2000 book, "Kind of Blue," is devoted exclusively to the making of this classic album and its lasting influence. Columbia (now Sony) has kept the album in print since it first appeared. In the past year it has released two different commemorative editions that include not only the original album but also false starts, studio chatter, the one alternate take of "Flamenco Sketches" and a previously unreleased live version of "So What." There are also excellent critical essays and a DVD that contains a gushing documentary on the album and a terrific tape of a 1959 television show on which Davis played "So What" with his combo and three big-band numbers arranged and conducted by Gil Evans. The more deluxe of these sets even includes a blue vinyl copy of the record. It is a testament to the original album's undiminished potency that none of this feels like overkill.

"Kind of Blue" has little historical import beyond its musical influence, but it makes a terrific cultural milestone against which we can measure a half century of change. Certainly the album made Davis a star—yes, in 1959 jazz musicians could still be pop stars—and in doing that it put before the public a black man unafraid to speak his mind and unwilling to compromise his art to please or appease anyone. In the materials accompanying the anniversary editions of the album, there is a picture of Davis draping his arms over pianist Bill Evans while demonstrating something on the keyboard. Today the picture seems innocuous, but in 1959 it could have caused a riot in certain parts of this country: a black man almost hugging a white man, a black man instructing a white man, a black man who was the white man's boss. It is a measure of just how polarizing a figure Davis was that he took criticism from both the white and the black communities. While Evans was a member of the band, Davis got an earful from black people who thought he should hire only African-Americans. In his public pronouncements, Davis could be intemperate, petulant and contrarian, but when it came to his music, he was always clearheaded and colorblind.

In 1959, jazz was more broadly popular than it is today—jazz was on the jukebox in '59—but it was still fighting for its place in the American cultural pantheon. It would be decades before anyone began calling it America's classical music (in 1965, when the music jury for the Pulitzer Prize voted to give the award to Duke Ellington, the Pulitzer board vetoed the decision). The battle is over now. Public schools teach jazz appreciation. Every major musical conservatory has a jazz department. Lincoln Center devotes two concert halls and a nightclub to jazz. Some of the excitement and sense of discovery that characterized the music at midcentury has leaked away in subsequent decades, but jazz still attracts new players, composers and audiences, and its influence is everywhere. Even the president of the United States boasts of having Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and Miles Davis on his iPod.

It would be foolish to credit "Kind of Blue" as the single tipping point in the debate, but considering its enormous popularity, it would be equally silly to ignore its influence. Millions of fans first encountered not just Miles Davis but jazz itself on this album, and it continues to define the form for new generations (almost half its sales have come in the past two decades). At a time when what is popular and what is good seem ever more divergent, "Kind of Blue" sounds better all the time.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.