I've just been back to London for a long weekend and caught the film Creation, which claims to tell the story of how Charles Darwin wrote On the Origin of Species. It's strong on Darwin the family man and how he was poleaxed by the death of his daughter, but less successful in conveying the world-changing implications of his theory of evolution.

Creation's producer complained that US distributors refused to touch it because they feared opposition from creationists. In the end the film did secure a limited American release, but the fuss made me wonder whether this portrayal of the naturalist as God-slayer will ever be seen in Africa.

I thought back to the Museum of Human Sciences, formerly the Queen Victoria Museum, in Harare. I met a museum guide who disapproved of his own exhibits, some rudimentary displays on the origins of life going back millions of years. "This is our section on evolution," he said. "But I don't believe it. I trust what it says in the Bible."

I asked him: "So Charles Darwin was wrong? You believe the world was created in seven days?" He smiled. "Yes, if the Bible says so."

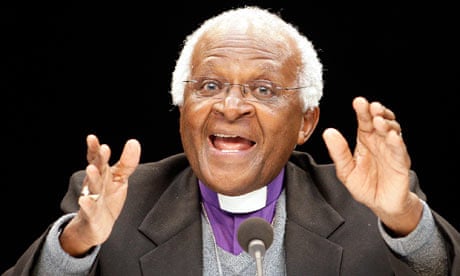

In South Africa, too, the atheist audience is not large. There is a wide mix of religions, with many black communities pragmatically combining a belief in the Christian God with traditional African practices honouring ancestral spirits. The archbishop Desmond Tutu is often seen as the conscience of the nation.

There have recently been warnings that Christian lobby groups could interfere in politics. Last month, a newspaper headline said: "Zuma's new God squad wants liberal laws to go." The Mail & Guardian reported that the National Interfaith Leadership Council, keen to revisit legislation permitting abortion and same-sex marriage, had the ear of the president, Jacob Zuma.

This is a country where the Zion Christian Church draws more than a million pilgrims each Easter, but also where the 20th annual gay pride march was held last weekend in a celebratory atmosphere. While the vast majority of South Africans apparently believe in the supernatural, their constitution reads like a secular liberal utopia.

In public discourse, there is no sense of US-style culture wars between film stars and Bible belt fundamentalists. Nor does there appear to be the British appetite for a Richard Dawkins or AC Grayling to do battle with the true believers in endless books, newspaper columns and set-piece debates.

Instead, science and religion seem content to maintain a truce and keep each other at arm's length.

A little-known but excellent stop in Johannesburg is the three-year-old Origins Centre, at Wits University. It traces the African roots of homo sapiens with a clear-eyed candour that would warm Dawkins's heart. Here, I feel certain, even the museum guides believe in Darwin.

There is a section on the San trance dance and how the Bushmen believe that it allows them to channel powers of healing. But it also includes a panel explaining the scientific reasons why dancing around a fire for hour after hour while the group sings and claps can produce altered states of consciousness.

The centre makes clear that even prehistory is political. Pride of place in the narrative is a discovery made a decade ago: in the Blombos cave, east of Cape Town, a team of archaeologists found cross-hatched engravings carefully etched on to red ochre stones. They were dated as 77,000 years old.

This not only dramatically pushed back the date of the first evidence of man's "modern" patterns of thought, it also changed the location. The symbolic engravings were twice as old as stone age cave paintings in southern France. In other words, rational, "modern" man originated in Africa, not Europe as previously claimed. A historic presumption – that man was born in Africa but learned to make art in Europe – is overturned, and the exhibition makes sure you get the point.

The theme is taken up in another room with a photograph of the so-called White Lady of Brandberg, a rock painting at Brandberg mountain, in Namibia. European explorers and archaeologists who found this elegant, enigmatic image in the early 20th century believed they could see a white woman in Egyptian, Cretan and Mediterranean styles.

They hailed it as sensational proof that it was sophisticated outsiders, not the indigenous, "backward" Bushmen, who had introduced art and civilisation to the region. Which would be all very well, except that modern analysis has shown that the figure has a penis, no breasts and carries a bow and arrows, which are male weapons. The colour of body paint is no indicator of race. The White Lady of Brandberg is, it transpires, neither white nor a lady.

Recently I visited the Cradle of Humankind, a visitor attraction near Johannesburg. It has a similar blend of skulls and statistics, as well as a Disney-style boat ride where you get blasted with cold air, and a brief display on Darwin to mark the bicentenary of his birth.

It answered one question at least. Whatever it thinks of him, we at least know what Darwin thought of South Africa. After visiting Cape Town in 1836, he said: "I saw so very little worth seeing that I have scarcely anything to say. I never saw a much less interesting country."