A man who was partially blinded when ammonia was squirted in his eye during an attack 15 years ago has regained his sight after receiving a pioneering stem cell treatment.

Russell Turnbull, 38, suffered massive damage to his right eye when he was caught in a scuffle after a night out in Newcastle in 1994. On the bus home, Turnbull had tried to intervene in a fight between two men but was injured when one of them began squirting passengers with ammonia.

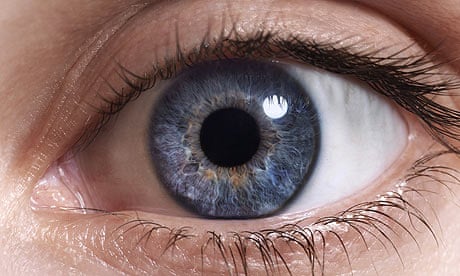

The chemical severely scarred Turnbull's cornea, the clear membrane that covers the front of the eye, and destroyed stem cells that usually help keep the cornea healthy.

"I was in unbearable pain. It burned my eye shut," Turnbull told the Guardian. "I was in hospital for two weeks and eventually I was able to open the eye again. It was like looking through scratched perspex."

Turnbull was left with "limbal stem cell deficiency" (LSCD), a condition that seriously impairs sight, and was in pain every time he blinked or saw bright lights.

In an experimental treatment devised by doctors at the North East England Stem Cell Institute in Newcastle, stem cells were taken from Turnbull's healthy eye and grown on a layer of amniotic tissue, which is routinely used as a burn dressing. The NHS banks amniotic sacs donated by women who have had a Caesarean section.

When the cells had covered the membrane, a piece the size of a postage stamp was transplanted onto Turnbull's damaged eye. Two months later the membrane had broken down, leaving his damaged eye with a fresh supply of healthy stem cells, which repaired the cornea.

Eye tests six months after surgery showed that Turnbull's vision was nearly as good as it had been before the attack.

"I had a lot of anger inside me for a long time after the attack. I lost my job because of it and I had always been a keen jet skier, which I wasn't able to do. It ruined my life and I went through a really difficult time. But then this treatment came along," said Turnbull.

"The pain and discomfort were better almost immediately and I started to get my sight back a month or so later. I used to be able to see only the largest letter at the top of the eye chart, but now I can pick out letters on the bottom row," he added.

Doctors led by Majlinda Lako and Francisco Figueiredo treated seven other patients, all of whom had LSCD in one eye. Some of the patients fully regained their eyesight, while others had more serious damage and experienced only limited improvement in their vision.

The study is published in the US journal Stem Cells.

Sajjad Ahmad, a member of the team, said 25 more patients will be treated before the results are submitted to Britain's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (Nice), which could approve the procedure for use in the NHS next year.